One of the important features of labour markets and

working conditions of workers in India that has always

been inadequately captured by our statistical system

is economic migration. The Census data collection

exercise is concerned only with current residence

and permanent migration. It does not even attempt

to capture short-term of seasonal flows of people,

and - because of its rather strict definition of permanent

migration - it even tends to leave out fairly prolonged

periods of migration.

The

National Sample Survey Organisation, until recently,

had also tended to ignore short-term migration. In

the 55th Round survey conducted in 1999-2000, some

questions were asked about those who worked away from

their normal residence for more than three months,

and this did provide some hints of evidence about

short-term migration for work. But micro studies indicated

that much of such movement is even more short-term

and often seasonal in character, and this was simply

not captured. The next large survey of 2004-05, the

61st Round, did not address the issue of migration

at all.

That is why the results of the 64th Round survey conducted

in 2007-08, with a special focus on migration, were

so eagerly awaited. Although it was a “small” survey

(the most recent large NSS survey was conducted over

2009-10), it was nevertheless large enough to give

us some useful indicators about some national and

state-level trends with respect to this feature. One

again, migration for work is only a subset of the

questions that were addressed, but the greater depth

of the questions and the revision of the time period

of movement with respect to which questions were asked

do provide some more data.

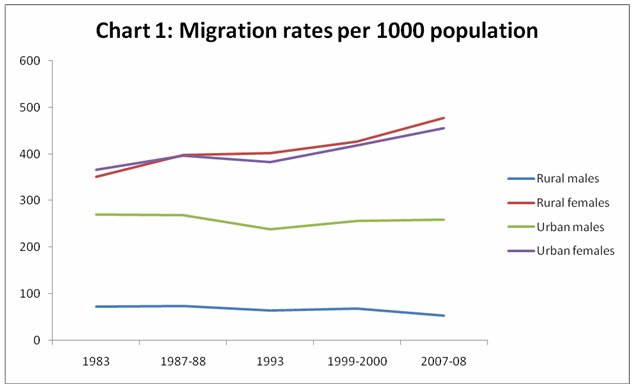

The basic trends in permanent or longer term migration

that are indicated from that survey are shown in Chart

1. There is a significant increase in migration rates

for females, but for urban males the rates are stagnant

and those for rural males have even declined somewhat.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

It is well known that the dominant

proportion of female migration in India is for purposes

of marriage, since most marriage patterns in the country

are based on virilocal residence. More than 91 per

cent of rural female migrants and 61 per cent of urban

female migrants had moved because of marriage. This

also explains why most of the migration (more than

90 per cent) in India is permanent in nature. Another

30 per cent of urban female migration was accounted

for by the need to move because the head of household

or main earning member had moved.

Since

female migration rates remain so strongly determined

by marriage, it is likely the male movement will better

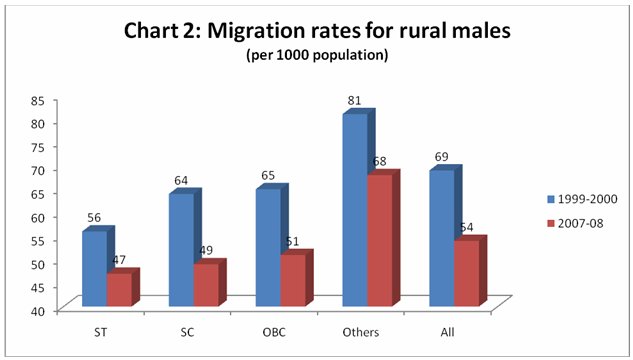

capture changing trends. Therefore Charts 2 and 3

provide the evidence on changing migration rates of

rural and urban males, respectively, by broad social

category.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

This is where the story becomes interesting. The latest

NSS survey actually shows a significant decline in

rural male migration rates (Chart 2), on average by

as much as 28 per cent compared to the previous survey.

The drop is evident across all social categories,

though it is largest for the SC and OBC categories.

This is possibly the first time that such declines

have been shown in the aggregate survey data, and

if this is a correct representation of reality it

is also likely to have implications for many other

trends, such as urbanisation and changing demographic

structures across different regions. Rural to urban

male migration increased by about 5 percentage points

compared to the previous survey, but it still accounted

for less than 40 per cent of total male migration.

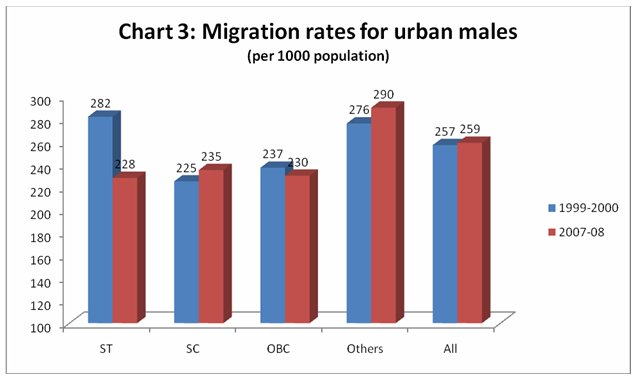

It

is also worth noting that such declines in migration

rates are not evident for urban males (Chart 3). In

fact, while migration rates for urban males of the

ST and OBC categories decreased to some extent, they

increased for SC and general categories, such that

the average rate increased slightly. One quarter of

all male migration was from one urban centre to another.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

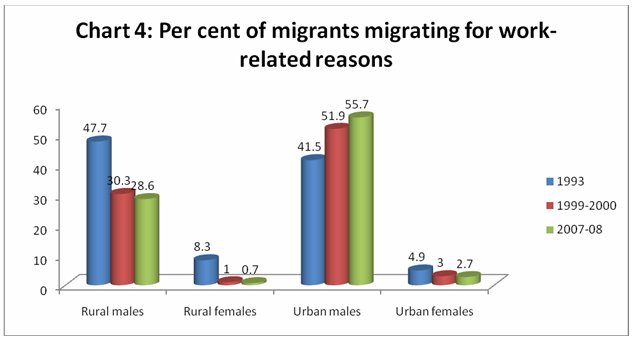

Similar

surprises are evident in terms of the causes of migration,

as shown in Chart 4. Work-related reasons (dominated

by the search of new or better employment) actually

accounted for falling proportions of the moves made

by rural residents, both male and female, even as

they continued to increase for urban males.

Chart

4 >> Click

to Enlarge

This is without question a noteworthy

development. What explains this trend? This issue

needs to be explored in much more detail, and with

more investigation into regional characteristics.

But it is possible that the introduction of the NREGA

has played some positive role in preventing the extreme

distress migration that was observed to characterise

many rural parts of the country.

Of

course, 2007-08 was still an early year for the programme,

which had not yet been extended to all the rural districts.

We may have to wait for the latest NSS survey to provide

some more information on this. The impact on rural

employment would be felt not only in terms of the

direct employment effects but also through the multiplier

effects of the incomes earned on what has been a very

depressed rural economy.

And of course, it is also possible that in addition

to positive factors, adverse features - such as the

fact that our urban areas have become less welcoming

or even tolerant of rural migrants - may also have

been significant. But certainly this survey shows

that even short-term migration, of between one to

four months, was relatively low and had probably decreased

since the previous survey.

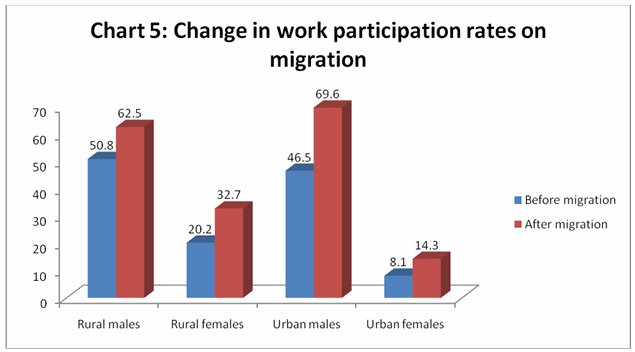

Chart

5 >> Click

to Enlarge

On

thing is clear though: once they move, migrants are

more likely to look for jobs and to find them (Chart

5). This is true of all categories of migrants, and

holds true whether they move for work-related reasons

or for any other reason. However, the survey also

shows that a growing proportion of the work that migrants

find is in the form of self-employment, indicating

the continuing difficulty in our growing economy,

of finding paid employment.

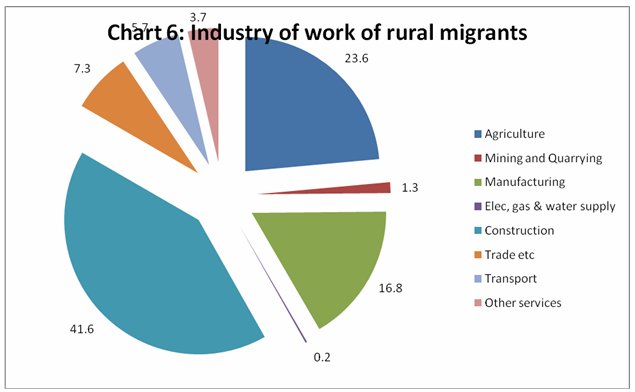

Construction

remains by far the dominant employer for rural migrants

(Chart 6) though agriculture accounts for the activity

of nearly a quarter. Manufacturing accounts for only

about 17 per cent of rural migrants’ work, a declining

proportion compared to the previous survey.

Chart

6 >> Click

to Enlarge

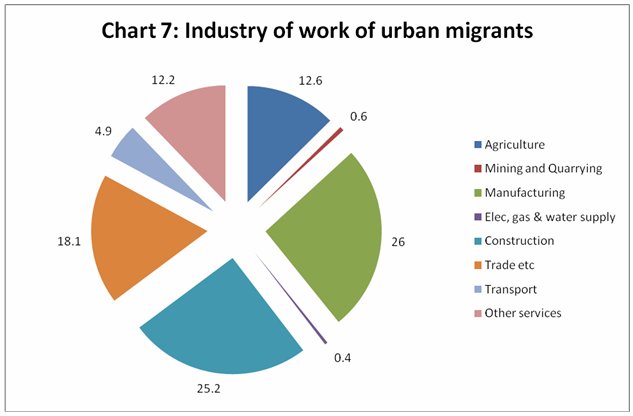

For

migrants from urban areas, construction and manufacturing

account for around equal shares of the activity (Chart

7) - amounting to just over half the work found. Trade,

hotels and restaurants are the other large employers

of migrants from urban areas.

Chart

7 >> Click

to Enlarge

There is obviously a great deal

more that is revealed by this latest migration survey

of the NSS, including the type of work, the remittances

sent, the details of the short-term employment, and

so on. But the early results already suggest that

there are some important changes in the pattern of

movement for work, especially for rural residents.

We need to consider more systematically how much this

is related to patterns of public intervention, and

also how public policy should address these changes.