What

has been the actual experience with ad revenue growth?

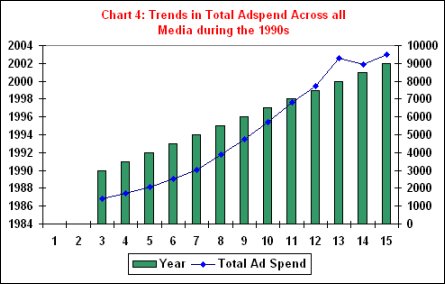

Chart 4 captures the trend in absolute newspaper ad-spend

and its share in total ad-spend points in two directions.

First, the share in ad-spend of the print media, which

declined marginally between 1990 and 1993 (73 to 69

per cent), fell sharply subsequently to touch a low

of 53.5 per cent in 1999. However, between 1999 and

2002, the print media was able to stop this erosion

partly through raising advertising rates. Thus, at

present, the threat to newspaper ad revenues in terms

of a reducing share of the advertising pie has been

stalled. Second, despite the decline in revenue share,

between 1990 and 2000, absolute newspaper advertising

revenues rose continuously because of a massive expansion

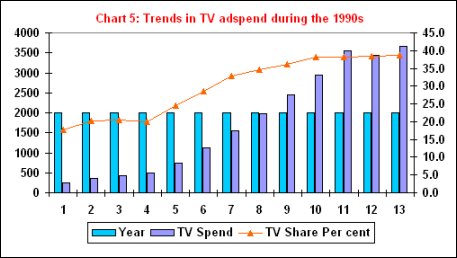

in total ad-spend (Chart 5). It is only during the

years in which newspapers were able to stall the erosion

in revenue shares that aggregate ad-spend, and therefore

newspaper advertising revenues, stagnated.

Chart

4 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart

5 >> Click

to Enlarge

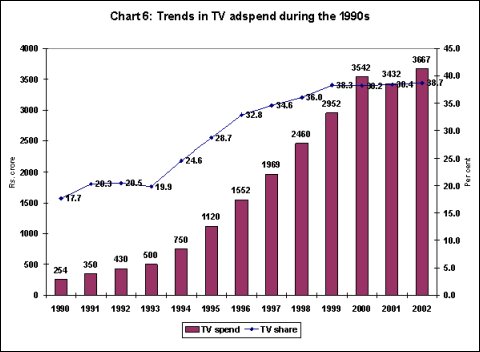

Chart 6, providing figures of

advertising revenue shares of television is an exact

mirror image of Chart 4, with revenue shares rising

sharply between 1993 and 1999 and stagnating thereafter.

On the other hand, as the same chart shows, since

aggregate ad-spend rose till 2000 and stagnated thereafter,

absolute advertising revenues in the TV business rose

quite sharply up to 1999, and the stagnated. It is

true that during the early years of expansion of private

satellite television in India, net revenues and profits

were completely driven by advertising revenues, since

the challenge of generating a viewership and competition

for eyeballs had encouraged a strategy of providing

their channels ‘free-to-air’. Revenues from consumers,

however limited, were monopolized by the distributors

via cable.

Chart

6 >> Click

to Enlarge

The sharp increase in television’s revenues and revenue

shares from advertising during the 1990s made this

a viable strategy. However, the stagnation of aggregate

ad-spend and of television’s share of that ad-spend

during 1999-2000, could lead to a shift in the competitive

game in the industry. Some observers argue that this

is unlikely to occur, since international trends suggest

that even now the share of ad revenues garnered by

the print media is high. Over time, print media shares

could go down to as low as 35 per cent if international

trends are replicated here.

But

there are a number of specificities of the Indian

marketplace that could make the recent stagnation

of relative ad revenue shares of newspapers and television

persist, or make the expected decline in newspaper

shares extremely gradual. To start with, given the

fact that literacy and basic education in India are

far from universal and that there is a strong relationship

between education, and income and spending power,

newspaper readers are a self-selected market for manufactures

and services of different kinds that are consumed

at income levels above a certain threshold. On the

other hand, given the nature of the medium, television

offers infotainment of a kind that is easily ‘consumed’

by those with lower levels of education and reach.

This does mean that beyond a point the expansion of

television’s reach in the Indian context need not

be into segments with the same levels of purchasing

power as the viewership at the pre-existing margin.

This could have implications for the media choice

of advertisers.

Second, it is known that different media are variously

suited to the advertising of different products. Advertisers

of so-called ‘fast-moving-consumer-goods’ or FMCG

products, who outlay huge budgets, are known to prefer

television for their products. But any advertising

that requires making a more elaborate case or offering

opportunities for recall are bound to choose the print

medium. It is possible that given the fact that the

Indian market is generated by a combination of a low

average per capita income and a highly skewed distribution

of that income, the structure of demand is such that

both newspapers and television have found their levels

of saturation in terms of advertising revenue shares.

Till further research provides more details, any judgement

on what is likely to happen to advertising revenue

shares must necessarily be speculative. All that can

be said is that if the recent trend of stagnation

in shares persists, an increase in the competition

among television channels for viewership, to which

advertising is linked, is inevitable. But competition

for viewership increases costs, leaving unresolved

the problem of sustaining net revenues or profits.

The fall-out of this could be two-fold. First, in

each market segment, created by the pluralism and

diversity inherent to India’s socio-cultural context,

only a few channel providers can survive in the long

run. Second, wherever possible, channel providers

will seek to exploit the option of turning into pay

channels, to directly obtain revenues from consumer.

The danger in the latter strategy is that even as

it would be facilitated by the conditional access

system (CAS), which resolves the ‘informational opaqueness’

and ‘conflict of interest’ problems associated with

the current distribution mechanism, a shift to CAS

would reveal the actual viewership of the channel

concerned, with obvious implications for advertising

revenues. This makes the choice of ‘turning pay’ one

that is open only to those channels that are obviously

successful in their niche and face no major competitive

threat. Overall, the tendency would be for an increase

in concentration in each market segment, which, as

in the case of print, is aggravated by the ‘winner-takes-all’

tendency resulting from the ‘herd instinct’ of advertisers.

In sum, the principal issue in the media business,

dominated by print and television, is not one of inter-media

competition but of the likelihood that in each market

segment within each kind of media business there is

a real threat of a kind of domination that dilutes

the basic tendency towards diversity and pluralism

characteristic of the Indian media marketplace.

This trend towards dilution is likely to be aggravated

by one other tendency specific to the two languages

which, for completely different reasons, command a

relatively large newspaper circulation: English and

Hindi. While these are individual languages, they

have been relatively insulated from the tendency towards

intra-language concentration because the circulation

in these languages is spread across large, sometimes

non-contiguous regions with varied socio-cultural

characteristics. Thus, the total circulation of these

dailies does not relate to one market but to a number

of market segments created by specific expectations

and habits of populations with diverse socio-cultural

characteristics. Not surprisingly, the number of newspapers

in these languages tends to be large, and different

market segments are dominated by different newspapers.

However, recent developments resulting from factors

captured by inadequately defined categories such as

‘globalization’ and ‘liberalization’, and the ‘dumbing

down’ driven by the more truly ‘mass’ medium of television,

are resulting in a homogenization of tastes in sections

of these segmented markets. In the event, a homogenized,

‘national’ market niche is emerging in these languages

that were earlier characterized by sharply segmented

markets.

In this context the drive to dominance takes two forms.

One is to tailor editorial styles to target the space

created by these homogenizing influences, with adverse

implications for serious and good journalism. The

second is to use aggressive competitive practices,

such as sharp reductions in the cover price, to ‘win’

a circulation share in the market currently dominated

by niche players and wean away a share of the advertising.

The latter strategy, it should be obvious, can be

pursued only by those with deep pockets. Smaller newspapers

with small advertising revenues would be unable to

sustain their editorial spending and their bottomlines

if they are to match the price reduction forced by

such practices. The tendency to use such practices

to increase dominance is thus disastrous for both

good journalism and for pluralism and diversity in

the print media, which has served Indian democracy

well.

All of this suggests that media policy in India must

take account of two needs. First, the need to preserve

the pluralism and diversity crucial to truly democratic

functioning, which may require finding ways to set

limits to the uncontested reach that media channels

(print or television) owned and controlled by a single

decision-making authority can have in any individual

language market segment. Larger reach of any single

entity must be accompanied by greater pluralism. Second,

since the real issue is not inter-media competition

but concentration in each market segment within each

medium, haphazard and uncontrolled growth in cross-media

control and ownership needs to be checked, because

that implies a degree of dominance and dilution of

pluralism and diversity that is doubly damaging.

References:

Bagdikian,

Ben H. (1997), The Media Monopoly, Fifth Edition,

Boston: Beacon Press.

Herman, Edward S and Robert W. McChesney (1997), The

Global Media: The New Missionaries of Corporate Capitalism,

London: Cassell.

Kumar, Sashi (2003), "The news according to Star",

The Hindu, Monday, July 28.

Ram, N. (2000), "The Great Indian

Media Bazaar: Emerging Trends and Issues for the Future",

in Romila Thapar (ed.), India:

Another Millenium?,

New Delhi: Viking.

Rao,

N. Bhaskara (2001), "Of content and control",

Frontline, Vol. 18 Issues 18, September 1-14.