| |

|

|

|

|

Budget 2004-05: The (Modified) Turnover

Tax |

|

| Aug

02nd 2004, Parthapratim Pal |

|

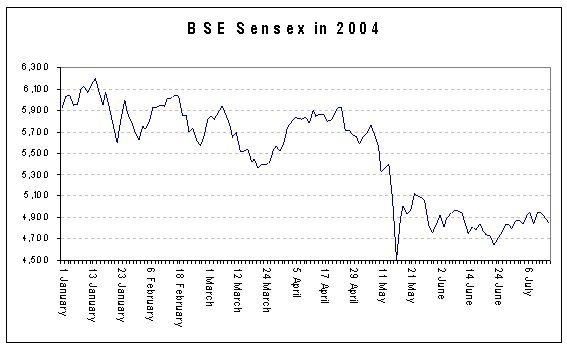

The

Securities Transaction Tax (STT) or the turnover tax

introduced in the Union Budget for 2004-05 has been

a controversial move. As an immediate impact of the

announcement of the STT, there was more than a hundred

point drop of the Bombay Stock Exchange sensitivity

index (Sensex). Though the Sensex partially recovered

subsequently, the threat of imposition of the turnover

tax led to protests by the brokers of stock exchanges

all over India. As a fallout of these protests, on

21st July 2004, the Finance Minister amended his proposals

by significantly lowering the tax burden and by proposing

a new STT regime with different tax rates for different

types of securities. Though this amendment has made

the stock market and day traders happy, it is likely

to result in significant revenue losses for the government.

Estimates suggest that the new STT will lead to a

revenue loss of Rs 6,000 to Rs 6,500 crores for the

fiscal year 2004-05. Given the fiscal constraints

faced by the government, it is difficult to understand

the rationale behind this tax rollback. Moreover,

as discussed in more detail later, the new STT is

more lenient towards non-delivery based short-term

trading and there is a possibility that it will encourage

speculative noise trading activities in the stock

market.

To put things into perspective, the imposition of

STT was not an isolated change. It was accompanied

by major reduction in the capital gains tax rate.

The finance minister proposed to abolish the current

10 percent tax on long-term capital gains from securities

transactions. In the case of short-term capital gains

from securities, he proposed to reduce the rate of

tax to a flat rate of 10 per cent . Currently, short

term gain is aggregated with taxable income from other

income classes and the short term capital gains tax

is levied at personal income tax rates. Against these

reductions in capital gains tax, he proposed to impose

the STT on transactions in securities on stock exchanges.

This tax was proposed to be levied at the rate of

0.15 per cent[1]

of the value of the security and would be payable

by the buyer of the security.

The benefits for imposing such a turnover tax, in

lieu of capital gains tax, are manifold. As Singh

(2004) discusses, the introduction of an

STT has the potential to curb excessive speculation

in the Indian stock market. Moreover, it was expected

that this new taxation policy would also help the

government to mobilize more revenue from the financial

investors.

However, the modified STT regime is considerably different

from the one proposed in the budget speech. The new

STT retains the 0.15 percent transaction tax only

on long term investors who take delivery of their

shares. Contrary to the original STT, in the new proposal

the buyer and seller will be splitting up the tax

burden equally between them. For day traders, arbitrageurs

and jobbers the tax rate has been brought down by

ten times from 0.15 percent to 0.015 per cent. Transaction

tax on derivatives has been brought down to 0.01 per

cent instead of the original proposal of 0.15 per

cent. Buying and selling of debt securities and bonds

including Government bonds have been totally exempt

from STT. It is interesting to note that though the

STT rates have been drastically revised downwards,

the finance minister has not reverted the capital

gains tax rates, which were lowered in the original

proposal.

One of the main reasons for imposing the STT was the

fact that most stock market players manage to avoid

or evade the capital gains tax. It was expected that

in a computerized system of stock market trading,

the transaction tax will act as a tamper proof and

low-cost method of collecting revenue from a section

of the population who pays relatively little tax.

However, the new STT brings the tax rates down by

a factor on ten for all short term and non-delivery

based trading in the market. This defies economic

logic as 55 to 60 percent of total stock market transactions

are short-term non-delivery based trade and because

of this reduction, the government is likely to face

a further resource crunch in the already constrained

fiscal situation. It is estimated that because of

the rollback of STT and the concurrent reduction in

capital gains tax rates, the total revenue earned

by the government from this instrument will come down

from Rs 7,000 crores to Rs. 1,000 crores only, causing

a massive shortfall of Rs 6,000 crores[2]

. It is not clear from where the finance minister

is going to cover this revenue loss. To put this shortfall

in perspective, the total allocation for rural employment

programmes in the Budget for 2004-05 is only Rs. 4,590

crores. From a principle of equity, it is difficult

to justify dolling out such fiscal largesse to a very

small group of relatively well-off people who are

involved in short term speculation[3].

It must be reiterated once again that long term investors

have not been given any new tax benefits in the modified

STT scheme.

This rollback of STT is going to take away most of

the other perceived benefits of the original STT system

as well. The new STT is essentially going to benefit

arbitrageurs and traders who indulge in very short

term speculative trading. This is likely to increase

the level of speculation in Indian stock markets.

Though it can be argued that speculation, which is

based on fundamentals, is essential for functioning

of the financial markets, it is well known that in

most stock markets, even in developed markets, fundamentals

play relatively little role in the determination of

stock prices[4].

This phenomenon is more widespread in developing country

markets where speculation and market manipulations

are more common. In India, repeated scams since 1992

have shown how stock market prices are manipulated

in this country. It will be extremely difficult for

anybody to argue that the wild mood swings of the

Sensex (Fig) can be explained by changes in the underlying

economic or financial fundamentals. In fact, to a

large extent, trading in the BSE is dominated by day

traders, who are essentially noise traders. Noise

traders are very short term speculators who trade

on thin margins and make their profits by trading

huge volume of securities. These transactions are

purely speculative, very short-term in nature and

are not based on economic or financial fundamentals

of the companies. It is unfortunate that the new STT

is going to benefit and promote precisely this type

of trading activity in the stock market. There is

a strong possibility that long-term investors will

be reluctant to enter the stock market if noise traders

can cause price of shares to decouple from their fair

value for long periods of time[5].

Increased speculative activity is also likely to increase

the volatility of share prices in India.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

Apart from day traders, another category of investors

who are likely to benefit from the new tax structure

is the foreign institutional investors (FIIs). In

the previous tax regime, FIIs were required to pay

30 percent tax on short term capital gains and 10

per cent tax on long term capital gains. However,

the Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA) between

India and Mauritius allows FIIs, who are registered

in Mauritius, to get away with much lower capital

gains tax rates. According to the DTAA, individuals

and companies that are residents of Mauritius will

pay their tax only in Mauritius and not in India.

Given the fact that Mauritius has no capital gains

tax, FIIs operating through that country effectively

do not pay any capital gains tax. However, these FIIs

are required to file their returns in India. The new

tax system will significantly reduce the tax burden

of the non-Mauritius based FIIs and will also reduce

the paperwork involved in filing capital gains tax

returns. The new tax structure also makes the Mauritius

route almost redundant and saves the FIIs from the

inconvenience of adding a layer to their operational

set up in that country. As additional sops to FIIs,

the investment ceiling for FIIs in debt funds has

been raised in the current budget to US$1.75 billion

from the existing ceiling of US$1 billion. The government

also proposes to make the procedures for registration

and operations of FIIs simpler and quicker to attract

greater inflow.

However, it is not clear why in every single budget

since 1992, FIIs are given special favours. FIIs are

already a dominant force in Indian stock markets.

Given the huge amount of foreign exchange reserves

available to India, the incremental benefit from increased

inflow of portfolio capital is minimal. In fact, recent

empirical evidence from a number of cross-country

studies has pointed out that among various forms of

foreign investments, foreign portfolio investment

is the least effective in promoting domestic investment

and growth. These studies reveal that the contribution

of portfolio investment to domestic capital formation

is lowest among different types of capital inflow.

Table 1 summarizes the main findings of some of these

studies.

Table

>> Click

to Enlarge

Also as Chandrasekhar

(2004) highlights, since 1992, India has

received an excess inflow of foreign portfolio investment

which is making macroeconomic management of the economy

extremely difficult. Given these problems with portfolio

investment, it makes little economic sense to keep

extending fiscal sops to portfolio investors.

To sum up the discussion, it can be said that the

original securities transaction tax (STT) was an innovative

idea to tax financial investors. It would have curbed

excessive speculative trading in Indian stock markets

and could have generated significant revenues for

the government. However, the finance minister's decision

to significantly alter the STT rates will now not

only allow a very high proportion of stock market

players to get away with paying very little tax but

it will also promote very short term and disruptive

speculative trading. In a year when the total allocation

for the National Common Minimum Programme has been

only Rs 10,000 crores, it is difficult to understand

why the finance minister relented to the pressure

from a few stock market players and effectively diluted

a major source of revenue earning for the government.

[1]

Short term capital gains from securities is defined

as profits made due to such sales within the year

[2] The Economic Times, 22 July 2004

[3] ''The brokers who were vocal last

week in their protests against the proposed 0.15 per

cent levy on daily turnover in securities transactions

have expectedly been identified as a group of 100-odd

arbitrageurs.'' -‘Sensexy, it's not – daily wagers

on the rampage', Nandu R Kulkarni in Mumbai, The Statesman,

July 12 2004. According to Sucheta Dalal: ''There

are 1,300 active brokers on the NSE and BSE's equity

segment and 75 in the debt market.'' In ‘Real impact

of transaction tax on people's life' Indian Express,

July 26th 2004.

[4]

For example, Shiller (1981,

1984) shows that changes in fundamentals could account

for only one-fifth of the high volatility in stock

prices. This observation is also supported by Campbell

and Shiller (1987), Fama and French (1988a, b), and

Poterba and Summers (1988).

[5]See

Noise

Trader Risk in Financial Markets' by De Long et.al

Bosworth

and Collins (1999), World Bank (1999) and World Bank

(2001)

|

|

Reference:

Bosworth, Barry, and Susan M. Collins. (1999): ''Capital

Flows to Developing Economies: Implications for Saving

and Investment.'' Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

1: 143–69.

Campbell, J. and R. Shiller. (1987): ''Cointegration

and Tests of Present Value Models.'' Journal of Political

Economy 95: 1062–87.

Bosworth

and Collins (1999), World Bank (1999) and World Bank

(2001)

Fama, E.F. & French, K.R. (1988a), ''Dividend Yields

and Expected Stock Returns'', Journal of Financial Economics,

Vol. 22, pp. 3-25.

Fama, E.F. & French, K.R. (1988b), ''Permanent and

temporary components of stock prices'', Journal of Political

Economy, Vol. 96, No. 2, pp. 246-270.

Poterba, J.M. and Summers, L.H. (1988), ''Mean reversion

in stock prices: evidence and implications'', Journal

of Financial Economics, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 27-59.

Shiller, R.J (1984): ''Stock Prices and Social Dynamics.''

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 457–92.

Shiller, R.J. (1981): ''Do Stock Prices Move Too Much

to be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends?''

American Economic Review 71: 421–36.

World Bank (1999): Global Economic Prospects and the

Developing Countries: Beyond Financial Crisis, Washington.

D.C.

World Bank (2001): Global Development Finance 2001,

Washington. D.C.

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|