It

is commonplace to decry the supposedly unsustainable

burden of subsidies on the state exchequer, and to

see desirable "reform" as the removal of such subsidies.

In his Budget Speech, Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee

lived up to this completely, and declared his intention

to bring down the subsidy bill particularly for fuel

and fertilizers. The Budget Estimates for 2012-13

indicate a decline in the fuel subsidy bill by as

much as Rs 25,000 crore. Clearly, if global oil prices

continue to remain high, this is a feat that cannot

be achieved without increasing fuel prices domestically.

It is unfortunate – but not altogether surprising

in the prevailing climate – that hardly any of the

commentary around the Budget pointed not just to the

severely inflationary implications of this, but also

the fact that this is unnecessary. Also, there is

a remarkable tendency in India to believe that this

particular price – which is after all the price of

the most essential universal intermediate, fuel –

should be equalized to global prices, even while per

capita incomes in India and the incomes of most consumers

remain so far below the global average.

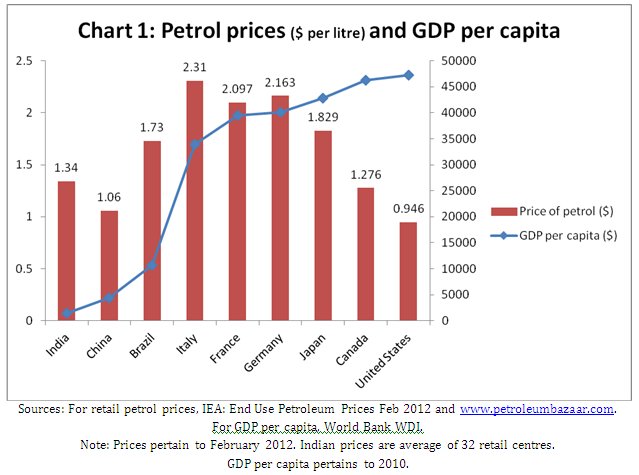

As it happens, retail prices of fuel in India are

among the highest in the world, and significantly

higher than in several developed countries including

the United States. Chart 1 shows that relative to

per capita income, Indian retail prices of petrol

are already extremely – and unreasonably – high. For

example, in February 2012 the Indian retail price

of petrol (averaged across 32 centres across the country)

was 42 per cent higher than in the US, and 26 per

cent higher than in China.

Chart

1 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

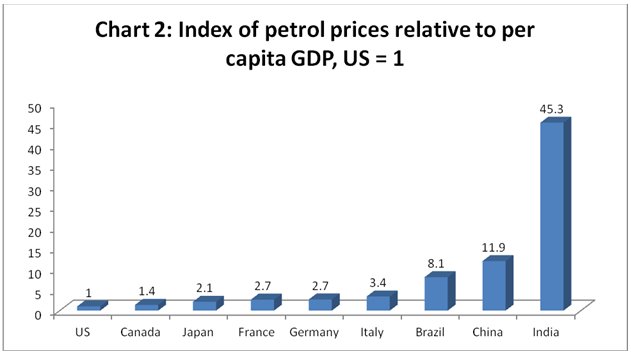

The full extent of this burden is apparent from Chart

2, which plots the ratio of petrol price to per capita

GDP in selected countries, in index form with the

ratio equivalent to 1 in the US (which has the lowest

such ratio among non-oil exporting countries). It

is clear that Indian consumers are being forced to

bear an inordinate burden relative to the average

purchasing power. Even compared to other developing

countries like Brazil and China, the burden is extreme.

And this does not take into account the inequalities

within the country which make the burden even more

onerous for poorer consumers.

The situation is similar for diesel prices, which

is what makes the matter more extreme. Diesel is close

to being a universal intermediate – entering into

costs faced by farmers, the cost incurred in much

other production and obviously the cost of transport.

High prices of diesel therefore feed directly and

indirectly into all other prices, including especially

the necessities consumed by the ordinary citizens.

Cutting subsidies that keep this price down is a direct

assault on the real incomes of the poor.

Chart

2 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

There is a further dishonesty in the government’s

approach to the issue, driven by the tendency to look

at the subsidy burden in isolation from the broader

elements of price formation, particularly the tax

regime. In fact, the petroleum sector is not a burden

on the government, but rather a cash cow that yields

large revenues in the form of customs duties and excise

duties. Since most of these duties are still specified

as ad valorem rates proportional to the value of the

commodity being taxed, revenues garnered from taxation

tend to rise along with the increase in the international

and domestic prices of the commodity. So in that sense

the government is fiscally a substantial gainer from

a period of high global fuel prices, even as it seeks

to put more burden on domestic consumers.

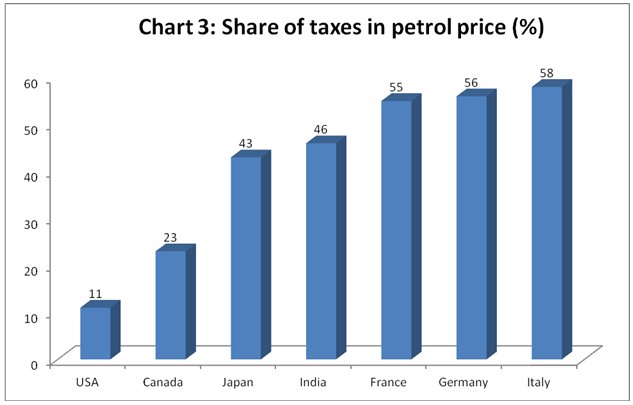

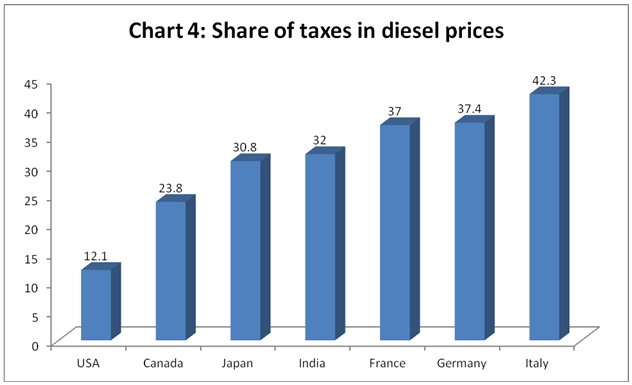

Charts 3 and 4 show the share of taxes in the retail

prices of petrol and diesel in selected countries

compared to India. It is evident that India is somewhat

in the middle of this group of developed countries,

which have on average per capita GDP that is nearly

thirty times that of India! In other words, the burden

of taxation of this essential good (which is necessarily

inherently regressive in character) is comparable

to countries with massively higher per capita incomes.

The contrast is particularly striking with respect

to the USA, since for petrol the tax burden in India

is four times that in the USA, while for diesel the

tax burden in India is nearly three times that in

the USA.

Chart

3 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

Chart

4 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

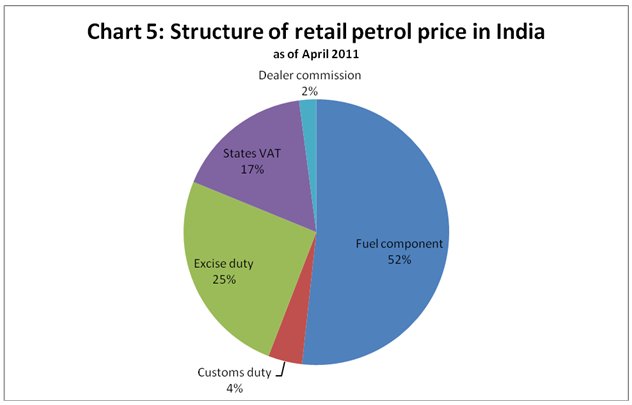

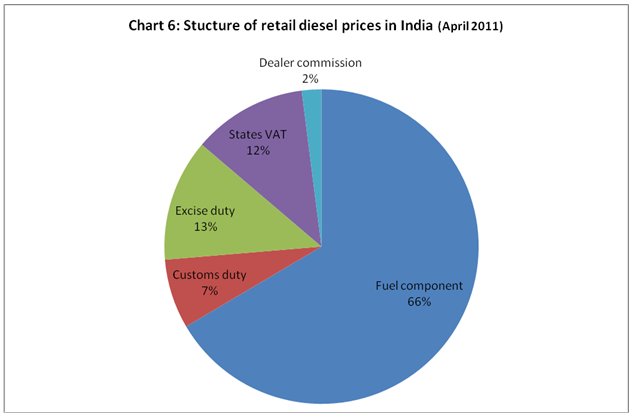

Charts 5 and 6 reveal the structure of components

of the retail price in India, based on data for April

2011 presented by the government in response to a

question raised in the Lok Sabha in 2011 (as quoted

in Rohit, "Economics behind the oil prices in India",

www.pragoti.org).

Chart

5 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

Chart

6 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

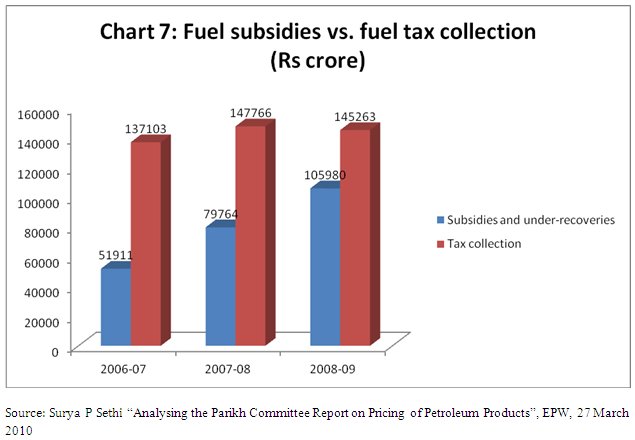

As it happens, the government’s tax collections from

petroluem products already far outweigh the subsidies

and under-recoveries from oil companies that consitute

the drain on the public exchequer. A study by Surya

P Sethi, former Energy Advisor to the Planning Commisison,

revealed that for the three years at the close of

the last decade, tax revenues from oil products had

been substantially higher than the outgo on subsidies

etc., even in that period of very high global oil

prices. Unfortunately more recent data on this are

no longer available on the website of the Petroleum

Planning and Analysis Cell.

Chart

7 >>

(Click to Enlarge)

The nature of the Budget Speech was such that the

actual measures to be taken with respect to petroleum

pricing were not elaborated. Rather, statements were

made that require action from other Ministries in

future, action that will necessarily involve raising

oil prices, with all the attendant adverse implications.

One point should be clear from this discussion: subsidies

in the energy sector are common across almost all

countries, including developed countries, and are

particularly necessary for developing countries like

India. The domestic price of oil cannot be set at

levels that recover the costs of import, since those

costs are too volatile and rising. Rather the domestic

price should be set on the premise that it is one

element in a tax-cum-subsidy framework, with the price

serving as part tax when international oil prices

are unduly low, and part subsidy when international

oil prices are as high as they are today.

This raises the critical issue of how a subsidy should

be viewed. Proponents of reduced fuel subsidies argue

that passing on rising prices and therefore getting

more "realistic" domestic price (that is

close to global market prices) would also encourage

more fuel-efficiency and reduce excess fuel consumption.

But this misses the point that the majority of Indian

citizens anyway have very low fuel consumption, and

it is only a small section of the population that

can afford to be profligate in its direct and indirect

fuel use.

Higher fuel prices in this context basically raise

costs for domestic producers in both agriculture and

non-agriculture, and have cascading inflationary effects

that attack the real incomes of the bulk of people

whose fuel consumption is already low. It is far better

to work for stability and containment of energy prices

while taxing the high-fuel consumption patterns of

the rich. So, taxes on luxury cars, air travel, generators

for domestic use or similar expenditure will all contribute

to the desired effect of controlling undesirably excessive

fuel consumption without attacking livelihoods and

living standards of all the people.

Avoiding these strategies and causing instead a regressive

increase in fuel prices is not an economic choice

– rather it is a choice about income distribution

and deciding to put the burden on the bulk of the

population rather than the privileged few.