Themes > Features

25.10.2002

The Paradoxical Behaviour of International Agricultural Commodity Prices

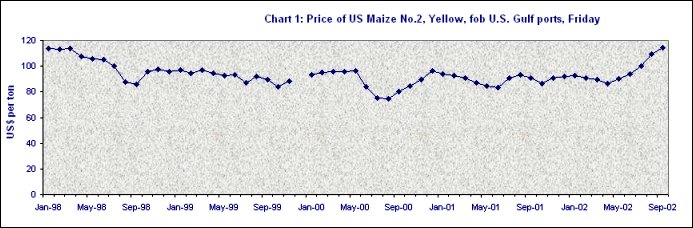

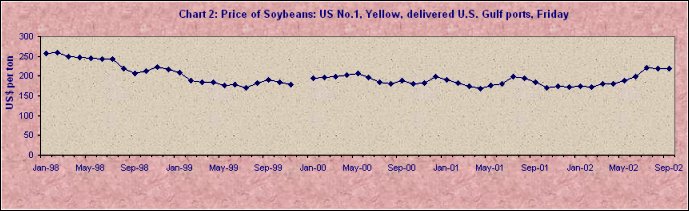

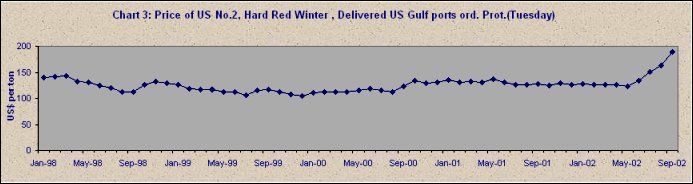

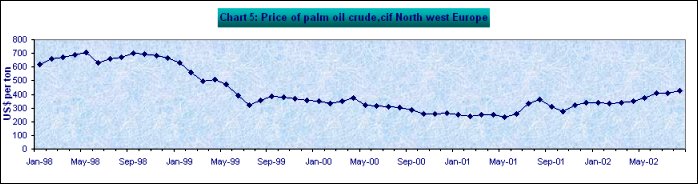

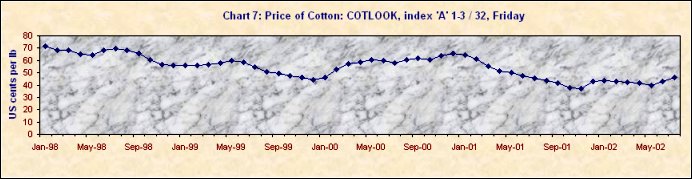

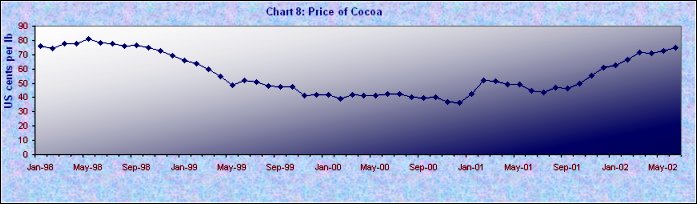

Recent

evidence suggests of a new trend in the world prices of agricultural

commodities. The price of US maize, which ruled at close to $85 a ton in

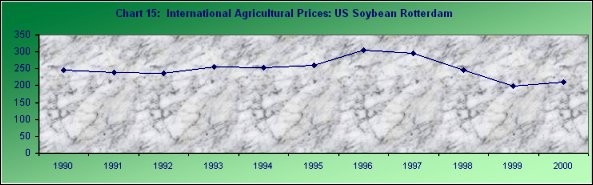

April 2002, rose by 35 per cent, to $115, by September. The price of

soybean jumped from $172 a ton in February to $220 by September, a rise of

28 per cent in seven months. US hard red winter wheat climbed from $123 a

ton in May to $190 (a 54 per cent rise), while the soft red variety moved

from $111 to $154 (a 39 per cent rise). Other commodities, like palm oil,

coconut oil, cotton and cocoa, also recorded similar price increases

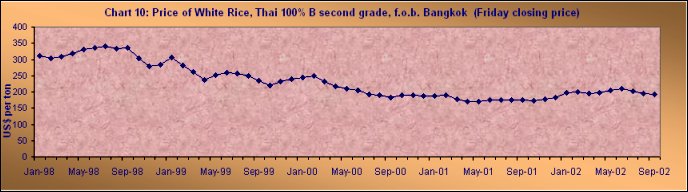

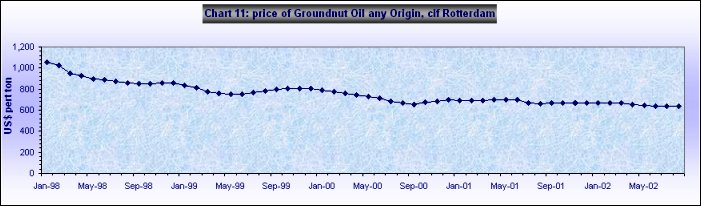

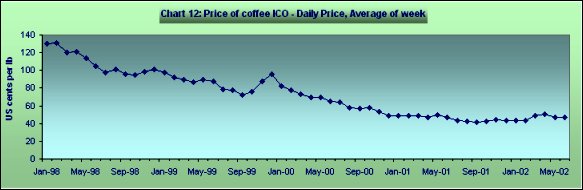

(Charts 1 to 8). The instances of stagnation or decline in the prices of

some commodities such as rice, groundnut and coffee (Charts 9 to 12),

appear to be exceptions rather than defining the rule.

These observed increases of between 25 and 55 per cent in the prices of

agricultural commodities within a relatively short period of time are

remarkable because they point to a new tendency in world commodity

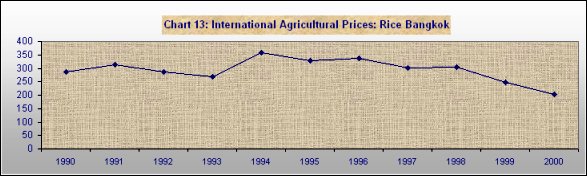

markets. Till recently, most agricultural commodities had been

experiencing long-run declines in their prices, starting from as far back

as 1994 (Charts 13 to 16), which was the year when the Agreement on

Agriculture (AoA), signed as part of the Uruguay Round of trade

negotiations, began to be implemented. Advocates of the AoA had at that

time argued that its implementation would result in a decline in developed

country exports of agricultural commodities, and in an increase in the

volume and prices paid for agricultural exports from developing countries.

This was to result in substantial welfare gains for the developing

countries. In practice, however, those promises remained unrealized as

commodity prices underwent a long-run decline. But if the new tendency for

prices to rise is sustained over the coming months, we could be witnessing

a major breakthrough for commodity producers in world markets.

While it is true that primary products as a whole accounted for just 30

per cent of developing country exports at the end of the 1990s as compared

to more than 90 per cent in the mid-1950s, and that the share of non-fuel

primary products (agricultural products and non-ferrous metals) in

developing country exports fell by nearly one half, to 12 per cent,

between the mid-1980s and late 1990s, agricultural exports are still

important to a large number of countries. According to figures collated by

the WTO, in the late 1960s, the large majority of developing countries,

103 out of 111 to be precise, were predominantly exporters of primary

products. Between 1968–70 and 1998–2000, only 27 of these made the

transition to being predominantly exporters of manufactured products and

76 remained primary product exporters, with a large number of them being

dependent on agricultural exports. The prospect of buoyancy in

agricultural prices is therefore of some significance to poor countries,

especially in Africa.

The recent signs of buoyancy are all the more remarkable because they

occur at a time when world economic growth is slow. Given the role of

supply-demand balances in determining the level of agricultural commodity

prices, the latter are known to be extremely sensitive to the business

cycle in the developed countries, rising in periods of boom and falling

during the downturn. With the IMF admitting that optimistic projections of

a sharp recovery in world economic growth during 2002 are not likely to be

realized, there seems to be no stimulus from the business cycle for world

prices of agricultural commodities.

It is widely accepted that the reason why agricultural commodity prices

did not respond favourably to the 'implementation' of the Uruguay Round

Agreement, is that domestic support and trade protection for agricultural

producers in the US and EU remained high, resulting in high levels of

production and large . OECD figures indicate that in 2001, transfers to

farmers amounted to more than $300 billion, which was equivalent to 31 per

cent of total farm income and 1.3 per cent of GDP. Overall, the volume of

support has by no means fallen since the beginning of the implementation

of the AoA, athough relative to farm income, support levels fell from 38

per cent in 1986–88 to 31 per cent in 1999–2001.

Many factors combined to contribute to this situation. First, with import

tariffs and export subsidies having been raised substantially by developed

country governments between 1980 and 1986, the reference level of tariffs

and subsidies relating to 1986–88 which provided the base for the

prescribed reduction in protection and support, was so high that the

actual reduction in protection and support did not involve much by way of

the freeing of trade. In the run up to the reference years 1986–88, the

developed countries massively hiked their support to agriculture in

different forms so that their so-called 'reduction commitment' was

virtually meaningless. The USA raised its Producer Subsidy Equivalent,

which is only part of its total transfers to farmers, from 9 per cent of

the value of agricultural production in 1980 to as much as 45 per cent by

1986, namely, a 500 per cent rise in the relative share alone, and a much

higher rise in the absolute sums involved. It was this highly inflated

transfer that then became the base for reduction, so that after reduction

the transfers still remain a multiple of what they were in 1980. Second,

the shift away from amber box subsidies to green and blue box subsidies,

which were conveniently defined as non-trade distorting and non-violative

of WTO norms, resulted in the aggregate support to agriculture in the OECD

countries rising over time.

The impact of such support and protection is felt in various ways. First,

by raising the prices paid by consumers in the OECD countries themselves,

through tariffs and subsidies, they hold back consumption of agricultural

commodities. Second, by protecting farmers' incomes, they encourage larger

production than would have otherwise been the case, resulting in more

supply and larger exports that tend to depress international prices.

It is not surprising, therefore, that world production of many

agricultural commodities did not decline as expected. As Table 1

indicates, in the case of many commodities, world production increased

continuously since 1994–95, while in a few production increased initially

only to decline during the closing years of the 1990s. What is more, the

developed countries, which accounted for 85 cent of world trade in

foodgrains when the implementation of the Uruguay Round Agreement began,

have remained important producers and suppliers of these commodities to

the world market.

As against this supply-side scenario, world demand has tended to be

depressed because of the adoption of deflationary policies in most

countries, and because of the contraction of economic activity in many

countries in the wake of the financial crises that afflicted them.

Needless to say, this deflationary tendency has worsened in more recent

times, when growth in the only countries that had registered some degree

of buoyancy during the second half of the 1990s, viz. the US and the UK,

has also tended to decline.

Persisting high supply combined with depressed demand conditions imply

that in the case of agricultural commodities, where demand and supply

factors still have a role in influencing market prices (even if not

farmers' incomes), prices can be expected to decline. And this is

precisely what happened in the years starting around the mid-1990s,

resulting in the promise held out by advocates of the UR Agreement—that it

would result in a rise in world prices of agricultural commodities, a

decline in developed country exports of such commodities and a rise in

developing country export volumes—remaining unrealized.

This is what makes the recent rise in prices even more surprising. As the

US Farm Bill 2002 makes clear, developed countries are by no means

reducing the income support they provide to their farmers. World output

and trade are now even more depressed than was the case in 2001 or

earlier, implying that world demand for primary commodities would also be

depressed. And agricultural prices continue to be determined by demand and

supply factors. What, then, explains the recent buoyancy in prices?

Three factors, clearly, have a role to play in this. The first is the

lagged effect of low prices on production, since direct income support has

increasingly been decoupled from production decisions, even if not

completely. The second is the spurred demand for agricultural commodities

resulting from sharply reduced prices. The net result of this has been

that the volume of stocks of individual commodities has tended to either

stagnate or decline. This basic tendency has been worsened in the case of

those commodities for which country-specific developments, such as drought

or pest attacks, have reduced world supply even further. Such factors have

been important in recent times. For example, according to the IMF's

World Economic Outlook: 'Grain prices edged up during the first half

of 2002, largely due to adverse weather conditions in the United States,

Canada, and Australia and consequent declines in global stocks. In the

near term, however, further price increases are limited by increased

competition from other producers such as Argentina and Brazil, while the

European Union may reinstate export subsidies. Vegetable oils and meals

prices have shown a more pronounced recovery than other agricultural

commodities, largely reflecting a reversal of extremely depressed levels

in 2000–01. Palm and coconut oil prices have increased owing to small

crops in major producer countries and reduced inventories; palm oil prices

have also been affected by large purchases in India and Pakistan to guard

against possible supply disruptions stemming from political conflict.'

The role played by these supply and demand adjustments to low prices can

be seen from Table 1, which shows that in the case of many commodities,

both output and stocks have tended to decline over the last two years. The

basic reason for the paradoxical buoyancy of prices in a period of

depressed economic conditions is to be found in these adjustments. That

is, when low or high prices prevail for long enough, the cobweb-type

behaviour expected in textbook analyses does in fact play a role, leading

to the unusual price behaviour characteristic of recent months.

To these we need to add the influence of a third factor: the role of

speculative holding of commodities that tends to increase in periods when

stockmarkets are depressed. There is reason to believe that the collapse

of stock markets in the wake of the busting of the tech boom and the

revelations of accounting fraud aimed at boosting share prices have

resulted in a flight to safety which has found liquidity increasing in

commodity markets. Since this happened at a time when production and stock

adjustments were in any case tending to raise prices, the sharp rise in

the prices of some commodities may be the result of speculative

influences.

Equity markets in the developed industrial countries were in free fall,

with what the IMF describes as 'surprising synchronicity', between

end-March and late-July 2002. Some degree of volatility since then has not

helped investors recoup the huge losses they incurred in recent months.

Those losses were the inevitable outcome of the winding-down of markets,

once it became clear that earlier profit figures had been inflated to

satisfy investors, that profit projections were unduly optimistic, and

that the 'recovery' in the US during the first quarter of 2002 was not

going to last. According to the IMF: 'In the face of increased risk and

uncertainty, demand for government bonds and high-quality corporate paper

has risen, which—together with expectations that monetary tightening will

be postponed—has driven long-run interest rates down significantly.

Spreads for riskier borrowers have risen, and risk appetite has also

declined.' Moreover, investors are now increasingly worried that the

dollar, which has thus far defied all laws of economic gravity and ruled

high despite record trade and current account deficits in the US, may in

fact weaken, necessitating a shift out of dollar-denominated financial

assets. In this context, what has also perhaps occurred is a shift of

investors from financial to real assets, especially commodities, based on

preliminary indications that commodity markets will remain firm because of

lower production levels and lower stocks. This too could be driving up

commodity prices, even if in the short run.

The simultaneous operation of all these factors comprises a possible

explanation for the unusual buoyancy of commodity prices. But since none

of these factors implies any change in the fundamental determinants of

agricultural commodity prices, which still work to depress those prices in

the long run, the observed buoyancy will, in all probability, be

shortlived.

© MACROSCAN 2002