Themes > Features

21.11.2003

Capital Flows, Changing patterns of Work and Gendered Migration: Implications for Women in China and Southeast Asia

The past two decades have been

momentous for the Asian region, and especially for

East and Southeast Asia. This is now the most

“globally integrated” region in the world, with the

highest average ratios of trade to GDP, the largest

absolute inflows of foreign direct investment,

substantial financial capital flows and even

significant movements of labour. These processes have

in turn been associated with very rapid changes in

forms of work and life, especially for women. Indeed,

the changes have been seismic in their speed,

intensity and effects upon economies and societies in

the region, and particularly upon gender relations.

The processes of rapid growth (and equally rapid and

sudden declines in some economies) have been

accompanied by major shifts in employment patterns and

living standards, as familiar trends are replaced by

social changes that are now extremely accelerated and

intensified.

We have thus observed, in the space of less than one generation, massive shifts of women’s labour into the paid workforce, especially in export-oriented employment, and then the subsequent ejection of older women and even younger counterparts, into more fragile and insecure forms of employment, or even back to unpaid housework. Women have moved – voluntarily or forcibly – in search of work across countries and regions, more than ever before. Women’s livelihoods in rural areas, dominantly in agriculture, have been affected by the agrarian crisis that is now widespread in most developing countries. Across societies in the region, massive increases in the availability of different consumer goods, due to trade liberalisation, have accompanied declines in access to basic public goods and services. At the same time, technological changes have made communication and the transmission of cultural forms more extensive and rapid than could even have been imagined in the past. All these have had very substantial and complex effects upon the position of women and their ability to control their own lives, many of which we do not still adequately understand.

In this paper, I will consider some of these processes and their possible implications for women in China and Southeast Asia. In the first section, some broad macroeconomic processes are briefly outlined, and then the effects upon women’s work in the region are discussed. In the second section, changing patterns of gendered migration are considered. The final section deals with the material, social and political implications for women in China and Southeast Asia.

Integration through trade and capital flows, and women’s work

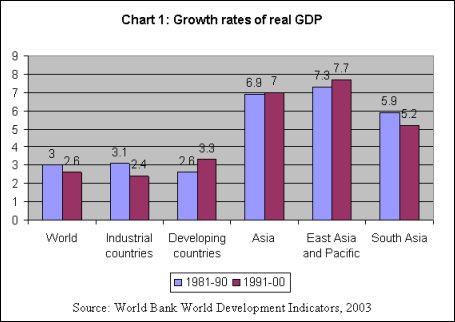

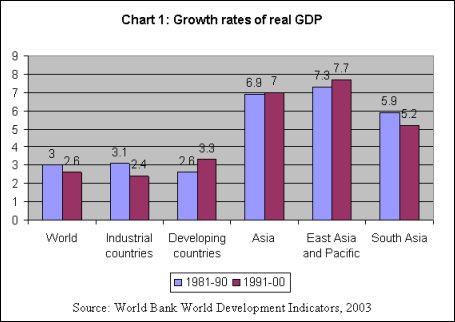

The Asian region as a whole is seen as the part of the world that has benefited the most from the process of globalisation. In terms of growth rates of aggregate GDP, as Chart 1 indicates, this region – and especially East Asia – far outperformed the rest of the world. High rates of growth in East Asia are of course dominated by the performance of China; however, in several countries of Southeast Asia such as Malaysia and South Korea, the relatively rapid recovery from the crisis of 1997-98 has added to the general perception of inherent economic dynamism in the region as a whole.

It is now commonplace to note that this economic expansion was fuelled by export growth. What is noteworthy is that until 1996, for most high-exporting economies except China, the rate of expansion of imports was even higher, and the period of high growth was therefore one of rapidly increasing trade-to-GDP ratios. For the whole of East and Southeast Asia and the Pacific, trade amounted to more than 60 per cent of GDP in the 1990s (Chart 2), which is historically unprecedented. Of course, Singapore and Hong Kong China have always had high trade-GDP ratios in excess of 200 per cent because of their status as entrepot nations, but even countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam have shown ratios greater than or approaching 100 per cent. Even the giant economy of the region, China, had a trade of GDP ratio of 44 per cent in 2001, and it is estimated to have increased further since then.

This very substantial degree of trade integration has several important macroeconomic implications. First, since these economies are heavily dependent upon exports as the engine of growth, they must rely either on rapid rates of growth of world trade which have not been forthcoming in the recent past) or increasing their shares of world markets. In the last decade the second feature has been more pronounced, but of course such a process has inevitable limits. These limits can be set either by rising protectionist tendencies in the importing countries, or by the competitive pressures from other exporting countries which give rise to the fallacy of composition argument. It has been noted (UNCTAD 2003) that such tendencies remain strong and have adversely affected terms of trade of high-exporting developing countries over the past decade, indicating that rapid increases in the volume of exports have not been matched by commensurate increases in the value of exports. This is turn means that the search for newer or increased forms of cost-cutting or labour productivity increases is still very potent. This is one reason why employment elasticities of export production have been falling throughout the region, and have also affected women’s employment in these sectors.

Second, the high rates of growth are matched or exceeded by very high import growth in almost all the economies of the region, barring China and Taiwan China, which are still generating substantial trade surpluses. The net effect on manufacturing employment is typically negative. This is obvious if the economy has a manufacturing trade deficit, but it is also the case even with trade balance or with small manufacturing trade surpluses, if the export production is less employment-intensive than the local production that has been displaced by imports. This is why, barring China and Malaysia, all the economies in the region have experienced deceleration or even absolute declines in manufacturing employment despite the much-hyped perception of the North “exporting” jobs to the South.[1] It should be noted that China, which accounted for more than 90 per cent of the total increase in manufacturing employment in the region, could show such a trend because imports were still relatively controlled until 2001, and because state owned enterprises continued to play a significant role in total manufacturing employment.

This region also experienced the most capital flows in the developing world from the mid-1980s until 1997. Thereafter, as Table 1 indicates, the Southeast Asian financial crises put a sharp brake on such inflows, other than FDI. It is well known that the rapid inflows of relocative FDI into Southeast Asia, especially from Japan, were crucially associated with the export boom in those countries. But from the mid-1990s, the FDI inflow reduced quite sharply in most countries of the region other than China. China, of course, remains the most significant developing country recipient of FDI inflow, and in 2002 achieved first position in the world in this regard, beating the US economy to second place. However, much of this FDI (around 60 to 70 per cent according to some estimates) is effectively “round-tripping” as unrecorded capital outflows come back in the form of Non-Resident Chinese investment because of the constraints that were placed upon resident private investors. In the period 1992-93 to 1996-97, FDI was replaced by fairly substantial inflows of finance capital in the form of either external commercial borrowing or portfolio capital, which caused real exchange rates to appreciate, led to current account deficits and therefore created the conditions for the subsequent crisis of 1997-98.

These other capital flows have been even more volatile and less reliable for Asia in the recent past. As Table 1 shows, net flows into the region have been negative or close to negative for the past four years. The huge build-up of foreign exchange reserves by the central banks of the Asian region over the first 9 months of 2003 (much of which is being held as securities or in safe deposits in the developed world, especially the US) suggests that net outflows in the current year are likely to be particularly large. So the East and Southeast Asian regions have experienced very sharp and large swings in capital flows over the past decade, which have also been associated with relatively large swings in real economies. The current capital export is really the result of reserve build-up because of central banks in the region attempting to prevent currencies from appreciating, as some of the lessons from the 1997 crisis are still retained by policy makers in the region.

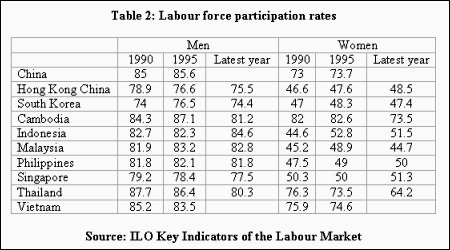

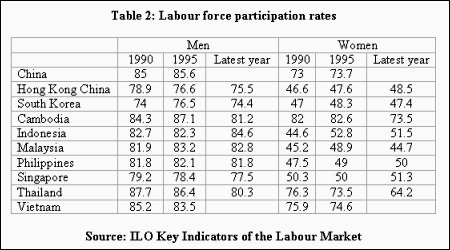

What this means, is that economies in the region are generally operating below the full macroeconomic potential, which in turn affects employment conditions, especially for women workers. In many countries of the region, as evident from Table 2, there has been a decline in female labour force participation rates since 1995. In some countries, such as Cambodia and Thailand, the decline has been quite drastic. Very few economies reported an increase (Philippines, Singapore, Hong Kong China), and these were relatively much less in magnitude. It is likely that reduced opportunities for productive employment have been responsible for the tendency for fewer women to report themselves as being part of the labour force, what is known in the developed countries as the “discouraged worker” effect.

Further, the defeminisation of export-oriented production at the margin, a process which began even earlier than the Asian financial crisis, has continued. It is now accepted that the relative increase in the share of women in total export employment, which was so marked for a period especially in the more dynamic economies of Asia, was a rather short-lived phenomenon. Already by the mid 1990s, women’s share of manufacturing employment had peaked in most economies of the region, and in some countries it even declined in absolute numbers. [2]

It is now apparent that even the earlier common assessment of the feminisation of work in East Asia had been based on what was perhaps an overoptimistic expectation of expansion in female employment. Trends in aggregate manufacturing employment and female employment in the export manufacturing sector over the 1990s in some of the more important Southeast Asian countries reveal at least two points of some significance. The first is that there is no clear picture of continuous employment in manufacturing industry over the decade even before the period of crisis. In several of these economies - South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong China - aggregate manufacturing employment over the 1990s actually declined. Only in Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand was there a definite upward trend to such employment.

Thus, while female employment in manufacturing was important, the trend over the 1990s, even before the crash, was not necessarily upward. In most of the countries mentioned, there is a definite tendency towards a decline in the share of women workers in total manufacturing employment over the latter part of the 1990s. In Hong Kong and South Korea, the decline in female employment in manufacturing was even sharper than that in aggregate employment. Similarly, even in the countries in which aggregate manufacturing employment increases over the period 1990-97, the female share had a tendency to stabilise or even fall. Thus, in Indonesia the share of women workers in all manufacturing sector workers increased from an admittedly high 45 per cent to as much as 47 per cent by 1993, and then fell to 44 per cent by 1997. In Malaysia the decline in female share was even sharper than in South Korea : from 47 per cent in 1992 to only 40 per cent in 1997. A slight decline was evident even in Thailand.

This fall in women’s share of employment is evident not just for total manufacturing but even for export-oriented manufacturing, and is corroborated by evidence from other sources. Thus Joekes [1999] shows that the share of women employed in EPZs declined even between 1980 and 1990 in Malaysia, South Korea and the Philippines, with the decline being as sharp as more than 20 percentage points (from 75 per cent to only 54 per cent) in the case of Malaysia.

The evidence suggests that the process of feminisation of export employment really peaked somewhere in the early 1990s (if not earlier in some countries) and that thereafter the process was not only less marked, but may even have begun to peter out. This is significant because it refers very clearly to the period before the effects of the financial crisis began to make themselves felt on real economic activity, and even before the slowdown in the growth rate of export production. So, while the crisis may have hastened the process whereby women workers are disproportionately prone to job loss because of the very nature of their employment contracts, in fact the marginal reliance on women workers in export manufacturing activity (or rather in the manufacturing sector in general) had already begun to reduce before the crisis.

In the subsequent period, manufacturing has tended to occupy a much less significant position in total employment of women. In Malaysia the share of women workers in manufacturing to all employed women fell from its peak of 31 per cent in 1992 to 26 per cent in 1999; in the Philippines from 13.3 per cent in 1991 to less than 12 per cent in 1999; in South Korea from its peak of 28 per cent in 1990 to 17 per cent in 2000; and in Hong Kong China from 32 per cent in 1990 to 10 per cent in 1999. [3]

In any case, the nature of such work has also changed in recent years. Most such work was already based on short-term contracts rather than permanent employment for women; now there is much greater reliance on women workers in very small units or even in home-based production, at the bottom of a complex subcontracting chain. Already this was a prevalent tendency in the region. For example, labour flexibility surveys in the Philippines have shown that the greater is the degree of labour casualisation, the higher is the proportion of total employment consisting of women and the more vulnerable these women are to exploitative conditions. [ILO 1995] This became even more marked in the post-crisis adjustment phase. [Pabico 1999]

In Southeast Asia, women have made up a significant proportion of the informal manufacturing industry workforce, in garment workshops, shoe factories and craft industries. Many women also carry out informal activities as temporary workers in farming or in the building industry. In Malaysia, over a third of all electronics, textile and garments firms were found to use sub-contracting. In Thailand, it has been estimated that as many as 38 per cent of clothing workers are homeworkers and the figure is said to be 25-40 percent in the Philippines [Sethuraman 1998]. Home-based workers, working for their own account or on a subcontracting basis, have been found to make products ranging from clothing and footwear to artificial flowers, carpets, electronics and teleservices. [Carr and Chen, 1999; Lund and Srinivas 2000]

This is of course part of a wider international tendency of somewhat longer duration : the emergence of international suppliers of goods who rely less and less on direct production within a specific location and more on subcontracting a greater part of their production activities. Thus, the recent period has seen the emergence and market domination of “manufacturers without factories”, as multinational firms such as Nike and Adidas effectively rely on a complex system of outsourced and subcontracted production based on centrally determined design and quality control. It is true that the increasing use of outsourcing is not confined to export firms; however, because of the flexibility offered by subcontracting, it is clearly of even greater advantage in the intensely competitive exporting sectors and therefore tends to be even more widely used there. Much of this outsourcing activity is based in Asia, although Latin America is also emerging as an important location once again. [Bonacich et al., 1994] Such subcontracted producers in turn vary in size and manufacturing capacity, from medium-sized factories to pure middlemen collecting the output of home-based workers. The crucial role of women workers in such international production activity is now increasingly recognised, whether as wage labour in small factories and workshops run by subcontracting firms, or as piece-rate payment based homeworkers who deal with middlemen in a complex production chain. [Beneria and Roldan, 1987; Mejia, 1997]

A substantial proportion of such subcontracting in fact extends down to homebased work. Thus, in the garments industry alone, the percentage of homeworkers to total workers was estimated at 38 per cent in Thailand, between 25-29 per cent in the Philippines, 30 per cent in one region of Mexico, between 30-60 per cent in Chile and 45 per cent in Venezuela. [Chen, Sebstad and O'Connell, 1998] Home-based work provides substantial opportunity for self-exploitation by workers, especially when payment os on a piece-rate basis; also these are areas typically left unprotected by labour laws and social welfare.

In addition, even other paid work performed by women has become less permanent and more casual or part-time in nature. In South Korea, one of the few countries for which such data is available, the proportion of employed women who casual contracts nearly doubled between 1990 and 1999; over the 1990s, around 60 per cent of all casual jobs were held by women workers.

Not only did paid employment conditions deteriorate in the region of women workers, but unpaid homework also tended to involve longer hours as the post-crisis adjustment process led to cuts in the provision of and access to public services. Only in China did paid employment for women workers, including in manufacturing, continue to grow – but even in China, services employment dominated in total employment for women, at more than 35 per cent. Gender wage gaps have narrowed slightly in most countries in the region, but they remain very high compared to other regions of the world.

Gendered migration patterns in Asia

Asia has become one of the most significant regions in the world not only in terms of the cross-border movement of capital and goods, but also in terms of the movement of people. Asian migration is not a new phenomenon historically, but in the last two decades, more women have moved than ever before. Within the Asian region, there is a complex and changing mix of countries of origin, destination and those that are both. The dominantly labour-sending countries in all of Asia include Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. The countries that are mainly destinations of host countries for migrant labour include all of those in the Middle East, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan China. Some countries are both sending and receiving international migrants: India, Malaysia, Pakistan and Thailand. Obviously, migration is a multidimensional phenomenon, which can have many positive effects because it expands the opportunities for productive work and leads to a wider perspective on many social issues. But it also has negative aspects, dominantly in the nature of work and work conditions and possibilities for abuse by employers and others.

Cross-border migration in Asia is highly gendered, with women migrants largely found in the service sector, especially in the domestic and care sectors, as well as in entertainment work. Male migration by contrast tends to be more in response to the requirements of industrialisation, in construction and manufacturing, as well as in semi-skilled services. Economic considerations are of course the primary reason for migration by individuals, especially women; but when this is large enough in sheer numbers, it has a substantial macroeconomic impact. Remittance incomes from migrant workers have shored up the balance of payments over the past decade in India and Philippines, to name just two countries. It is worth noting that female migrant workers are less affected by business cycle phenomena in the host countries, because of the different nature of activities in which they tend to be employed; therefore, both female migration and remittances from such migration have in general been more stable than the male versions in the recent period.

However, despite the growing significance of female migration in the region, there is little recognition by officialdom in the relevant Asian governments of this process, in terms of ensuring decent working conditions and remuneration for migrants.

Over the past decades, women migrants have come dominantly from three countries in Asia: the Philippines, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. In the Philippines, women migrants have outnumbered their male counterparts since 1992, and in all these countries women are between 60 to 80 per cent of all legal migrants for work. The majority are in services (typically low paid domestic service) or in entertainment work. While Filipino women tend to travel all over the world, women from the other two countries go dominantly to the Middle East and Gulf countries in search of employment. Elsewhere in the region, restrictive regulations have reduced legal female emigration, but may have increased illegal migration, or trafficking.

Migrants typically tend to fill unskilled, labour-intensive and low-paid jobs, and are generally unprotected by labour laws. While male migrants in the region are usually (but not exclusively) in the 3-D occupations (difficult, dirty, dangerous), women migrant workers tend to be concentrated in the low paid sectors of the service industry, in semi-skilled or low-skilled activities ranging from nursing to domestic service, or in the entertainment, tourism and sex industries where they are highly vulnerable and subject to exploitation. They rarely have access to education and other social services, have poor and inadequate housing and living conditions. When they are illegal or quasi-legal and dependent upon contractors, they also find it difficult to avail of existing facilities such as proper medical care and are almost never found to organise to struggle for better conditions. In general, host governments are less than sympathetic to the concerns of migrant workers, including women, despite the crucial role they may play in the host economy. Host country governments tend to view migrants as threats to political and social stability, additional burdens on constrained public budgets for social services and infrastructure, and potential eroders of local culture.

This is why there is so little attempt across the region to ensure decent conditions of migrants, even in terms of ensuring their basic safety and freedom from violence. This is an important issue for women migrants in particular, since they are specially vulnerable to sexual exploitation, not only when they are workers in the entertainment and sex industries, but also when they are employed in other service activities or in factories as cheap labour.

There is often a fine line between voluntary migration and trafficking in women (and girl children). Trafficking is a widespread problem which is on the increase, not only because of growing demand, but also because of larger and more varied sources of supply given the increasingly precarious livelihood conditions in many rural parts of Asia.

A substantial amount of trafficking of both women and children occurs not only for commercial sex work, but also for use as slave labour in factories and other economic activities such as domestic or informal service sector work. It is true, of course, that the worst and most abusive forms of trafficking are those which relate to commercial sexual exploitation and child labour in economic activities. Nor is it the case that trafficking occurs mainly through coercion or deception: there is significant evidence to indicate voluntary movement by the women themselves, especially when home conditions are already oppressive or abusive, or at least voluntary sending by the households of such individuals, given the poverty and absence of economic opportunities in the home region. Traffickers throughout Asia lure their victims by means of attractive promises such as high paying jobs, glamorous employment options, prosperity and fraudulent marriages. When there is employment, however badly paid, precarious and in terrible conditions, it may still be preferred to very adverse home circumstances. This in turn means that those who are employed through trafficking may not always desire to return home, if the adverse economic and social persist. Also, the possibilities of return to home communities with safety and dignity are often limited, given the possibilities of being stigmatised and not easily reintegrated into the home society.

All this makes the problem of dealing with trafficking much more complex than is generally appreciated. From the point of view of attacking the causes, it is important to address the issues of economic vulnerability, marginalization and attitudes to women, which encourage such movement. Environmental disasters and development-induced risks such as displacement are also known to play a role in increasing the incidence of trafficking.

Obviously, across the region there is need for more pro-active policies regarding migration. It is unfortunate that most government policies with respect to migration are designed with the male breadwinner model in mind, because this effectively excludes women, especially those who are trafficked, from the purview of regulation and protection by law. Very easy immigration policies can create routes for easier trafficking; but conversely, tough immigration policies can drive such activities underground and therefore make them even more exploitative of the women and children involved. The specificities and complexities of the trafficking processes, as well as the economic forces that are driving them, need to be borne in mind continuously when designing the relevant policies. Across the region, there is hardly any host country legislation specifically designed to protect migrant workers, and little official recognition of the problems faced by women migrants in particular. The same is true for the sending countries, which accept the remittances sent by such migrants, but without much fanfare or gratitude, and with little attempt to improve the conditions of these workers in the employment abroad. Women migrants, who typically are drawn by the attraction of better incomes and living conditions or by very adverse material conditions at home, are therefore is a no-woman’s land characterised by a generalised lack of protection.

Recently there is also a trend for increased migration by more educated women workers, in the software and IT-enabled service sectors. While such female migration is still a very small part of the total, it is pointing to a different tendency with different implications both for work patterns and for gender relations in both sending and receiving countries.

Conclusion

The picture of women’s employment and migration in Asia today is much more complex than it has appeared for some time. There have been some clear gains from the relatively short-lived process of using much more women’s labour in the greater export-oriented production of the region. One important gain is the social recognition of women’s work, and the acceptance of the need for greater social protection of women workers. The fact of greater entry into the paid work sphere may have also provided greater recognition of women’s unpaid household work. At the same time, however, such unpaid work has tended to increase because of the reduction of government expenditure and support for many basic public services, especially in sanitation, health and care-giving sectors. Recent reversals in the feminisation of employment also point to the possibility of regression in terms of social effects as well. Already, we have seen the rise of revivalist and fundamentalist movements across the Asian region, which seek to put constraints upon the freedom of women to participate actively in public life. This process is not new to capitalism: in the United States, women were actively encouraged to participate in paid work to fill in for labour shortages created by the war during the second World War, only to be thrust back into unpaid household work almost immediately once the war was over. However, the speed and extent of the equivalent processes in Asia still have the capacity for creating major social changes which can have destabilising effects on gender relations and on the possibilities for the empowerment of women generally. At the same time, advances in communication technology and the creation of the “global village” provide both threats and opportunities. They encourage adverse tendencies such as the commodification of women along the lines of the hegemonic culture portrayed in international mass media controlled by giant US-based corporations, and the reaction to that in the form of restrictive traditionalist tendencies. But the sheer knowledge of conditions and possibilities elsewhere can have an important liberating effect upon women, which should not be underestimated.

References

Asis, Maruja M. B. [2003] “Asian women migrants: Going the distance, but not far enough”, mimeo

Beneria, L., and M. Roldan [1987], The Crossroads of Class and Gender: Homework Subcontracting and Household Dynamics in Mexico City, Chicago, University of Chicago Press

Bonacich et al, (eds) Global Production: The Apparel Industry in the Pacific Rim, Temple University Press: Philadelphia.

Carr, Marilyn and Martha Alter Chen [1999] “Globalisation and home-based workers”, WIEGO Working Paper No. 12.

Ghosh, Jayati [1999b] “Trends in economic participation and poverty of women in the Asia-pacific region”, UN-ESCAP Bangkok, also available at website http://www.macroscan.com

Ghosh, Jayati and C. P. Chandrasekhar [2001] Crisis as Conquest: Learning from East Asia, New Delhi: Orient Longman.

Ghosh, Jayati and C. P. Chandrasekhar (eds) [2003] Work and well being in the age of finance, New Delhi: Tulika Books.

Ghosh, Jayati [2003a] “Where have the manufacturing jobs gone? Production, accumulation and relocation in the world economy” in Ghosh and Chandrasekhar (eds).

Ghosh, Jayati [2003b] “Globalisation, export-oriented employment for women and social policy: A case study of India” in Shahra Razavi and Ruth Pearson (eds) Gender and export employment, Palgrave

Harrison, Bennett and Maryellen Kelley [1999] "Outsourcing and the search for flexibility: The morphology of contracting out in US manufacture," in Pathways to Industrialization and Regional Development in the 1990s, Boston, Unwin and Hyman.

Heyzer, Noeleen, ed [1988] Daughters in Industry: Work Skills and Consciousness of Women Workers in Asia, Asia and Pacific Development Centre, Kuala Lumpur

Horton, Susan, ed [1995] Women and Industrialisation in Asia, London : Routledge

ILO [1995] "Women at work in Asia and the Pacific - Recent trends and future challenges", in Briefing Kit on Gender Issues in the World of Work, Geneva

Joekes, Susan [1999] “A gender-analytical perspective on trade and sustainable development”, Trade, Gender and Sustainable Development, UNCTAD, Geneva.

Joekes, Susan and Ann Weston [1994] Women and the New Trade Agenda, UNIFEM, New York

Kibria, Nazli [1995] "Culture, social class and income control in the lives of women garment workers in Bangladesh", Gender and Society, Vol 9 No 3, June, pp 289-309

Korean Working Women’s Network [1998] “Organisational strategies pf irregular women workers”, Seoul, available at http://www.kwwnet.org.

Lee, Hyehoon [2001] “Evaluation and promotion of social safety nets for women affected by the Asian economic crisis”, Expert Group Meeting on Social Safety Nets for Women, UNESCAP, Bangkok

Lim, Lean Lin [1994] "Women at work in Asia and the Pacific: recent trends and future challenges", Paper for International Forum on Equality for Women in the World of Work, Geneva, ILS

Lim, Lin Lean [1996] More and Better Jobs for Women : An action guide, ILO Geneva

Malapit, Hazel Jean [2001] “A review of literature on gender and trade in Asia”, Asian Gender and Trade Network, www.genderandtrade.org.

Mejia, R. [1997] “The impacy of globalisation on women workers”, in The Impact of Globalisation on Women Workers : Case Studies from Mexico, Asia, South Africa and the United States, Oxfam.

Meng, Xin [1998] “The economic position of women in Asia”, CLARA Working Paper No. 4, Amsterdam

Rayanakorn, Kobkun [2002] “Gender inequity”, mimeo

Tullao, Teresa and Michael Angelo Cortez [2003] “Movement of natural persons and its human development implications in Asia”, UNDP mimeo.

Wee, Vivienne (ed) [1998] Trade liberalisation: Challenges and opportunities for women in Southeast Asia, UNIFEM and ENGENDER, New York and Singapore

We have thus observed, in the space of less than one generation, massive shifts of women’s labour into the paid workforce, especially in export-oriented employment, and then the subsequent ejection of older women and even younger counterparts, into more fragile and insecure forms of employment, or even back to unpaid housework. Women have moved – voluntarily or forcibly – in search of work across countries and regions, more than ever before. Women’s livelihoods in rural areas, dominantly in agriculture, have been affected by the agrarian crisis that is now widespread in most developing countries. Across societies in the region, massive increases in the availability of different consumer goods, due to trade liberalisation, have accompanied declines in access to basic public goods and services. At the same time, technological changes have made communication and the transmission of cultural forms more extensive and rapid than could even have been imagined in the past. All these have had very substantial and complex effects upon the position of women and their ability to control their own lives, many of which we do not still adequately understand.

In this paper, I will consider some of these processes and their possible implications for women in China and Southeast Asia. In the first section, some broad macroeconomic processes are briefly outlined, and then the effects upon women’s work in the region are discussed. In the second section, changing patterns of gendered migration are considered. The final section deals with the material, social and political implications for women in China and Southeast Asia.

Integration through trade and capital flows, and women’s work

The Asian region as a whole is seen as the part of the world that has benefited the most from the process of globalisation. In terms of growth rates of aggregate GDP, as Chart 1 indicates, this region – and especially East Asia – far outperformed the rest of the world. High rates of growth in East Asia are of course dominated by the performance of China; however, in several countries of Southeast Asia such as Malaysia and South Korea, the relatively rapid recovery from the crisis of 1997-98 has added to the general perception of inherent economic dynamism in the region as a whole.

It is now commonplace to note that this economic expansion was fuelled by export growth. What is noteworthy is that until 1996, for most high-exporting economies except China, the rate of expansion of imports was even higher, and the period of high growth was therefore one of rapidly increasing trade-to-GDP ratios. For the whole of East and Southeast Asia and the Pacific, trade amounted to more than 60 per cent of GDP in the 1990s (Chart 2), which is historically unprecedented. Of course, Singapore and Hong Kong China have always had high trade-GDP ratios in excess of 200 per cent because of their status as entrepot nations, but even countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam have shown ratios greater than or approaching 100 per cent. Even the giant economy of the region, China, had a trade of GDP ratio of 44 per cent in 2001, and it is estimated to have increased further since then.

This very substantial degree of trade integration has several important macroeconomic implications. First, since these economies are heavily dependent upon exports as the engine of growth, they must rely either on rapid rates of growth of world trade which have not been forthcoming in the recent past) or increasing their shares of world markets. In the last decade the second feature has been more pronounced, but of course such a process has inevitable limits. These limits can be set either by rising protectionist tendencies in the importing countries, or by the competitive pressures from other exporting countries which give rise to the fallacy of composition argument. It has been noted (UNCTAD 2003) that such tendencies remain strong and have adversely affected terms of trade of high-exporting developing countries over the past decade, indicating that rapid increases in the volume of exports have not been matched by commensurate increases in the value of exports. This is turn means that the search for newer or increased forms of cost-cutting or labour productivity increases is still very potent. This is one reason why employment elasticities of export production have been falling throughout the region, and have also affected women’s employment in these sectors.

Second, the high rates of growth are matched or exceeded by very high import growth in almost all the economies of the region, barring China and Taiwan China, which are still generating substantial trade surpluses. The net effect on manufacturing employment is typically negative. This is obvious if the economy has a manufacturing trade deficit, but it is also the case even with trade balance or with small manufacturing trade surpluses, if the export production is less employment-intensive than the local production that has been displaced by imports. This is why, barring China and Malaysia, all the economies in the region have experienced deceleration or even absolute declines in manufacturing employment despite the much-hyped perception of the North “exporting” jobs to the South.[1] It should be noted that China, which accounted for more than 90 per cent of the total increase in manufacturing employment in the region, could show such a trend because imports were still relatively controlled until 2001, and because state owned enterprises continued to play a significant role in total manufacturing employment.

This region also experienced the most capital flows in the developing world from the mid-1980s until 1997. Thereafter, as Table 1 indicates, the Southeast Asian financial crises put a sharp brake on such inflows, other than FDI. It is well known that the rapid inflows of relocative FDI into Southeast Asia, especially from Japan, were crucially associated with the export boom in those countries. But from the mid-1990s, the FDI inflow reduced quite sharply in most countries of the region other than China. China, of course, remains the most significant developing country recipient of FDI inflow, and in 2002 achieved first position in the world in this regard, beating the US economy to second place. However, much of this FDI (around 60 to 70 per cent according to some estimates) is effectively “round-tripping” as unrecorded capital outflows come back in the form of Non-Resident Chinese investment because of the constraints that were placed upon resident private investors. In the period 1992-93 to 1996-97, FDI was replaced by fairly substantial inflows of finance capital in the form of either external commercial borrowing or portfolio capital, which caused real exchange rates to appreciate, led to current account deficits and therefore created the conditions for the subsequent crisis of 1997-98.

These other capital flows have been even more volatile and less reliable for Asia in the recent past. As Table 1 shows, net flows into the region have been negative or close to negative for the past four years. The huge build-up of foreign exchange reserves by the central banks of the Asian region over the first 9 months of 2003 (much of which is being held as securities or in safe deposits in the developed world, especially the US) suggests that net outflows in the current year are likely to be particularly large. So the East and Southeast Asian regions have experienced very sharp and large swings in capital flows over the past decade, which have also been associated with relatively large swings in real economies. The current capital export is really the result of reserve build-up because of central banks in the region attempting to prevent currencies from appreciating, as some of the lessons from the 1997 crisis are still retained by policy makers in the region.

What this means, is that economies in the region are generally operating below the full macroeconomic potential, which in turn affects employment conditions, especially for women workers. In many countries of the region, as evident from Table 2, there has been a decline in female labour force participation rates since 1995. In some countries, such as Cambodia and Thailand, the decline has been quite drastic. Very few economies reported an increase (Philippines, Singapore, Hong Kong China), and these were relatively much less in magnitude. It is likely that reduced opportunities for productive employment have been responsible for the tendency for fewer women to report themselves as being part of the labour force, what is known in the developed countries as the “discouraged worker” effect.

Further, the defeminisation of export-oriented production at the margin, a process which began even earlier than the Asian financial crisis, has continued. It is now accepted that the relative increase in the share of women in total export employment, which was so marked for a period especially in the more dynamic economies of Asia, was a rather short-lived phenomenon. Already by the mid 1990s, women’s share of manufacturing employment had peaked in most economies of the region, and in some countries it even declined in absolute numbers. [2]

It is now apparent that even the earlier common assessment of the feminisation of work in East Asia had been based on what was perhaps an overoptimistic expectation of expansion in female employment. Trends in aggregate manufacturing employment and female employment in the export manufacturing sector over the 1990s in some of the more important Southeast Asian countries reveal at least two points of some significance. The first is that there is no clear picture of continuous employment in manufacturing industry over the decade even before the period of crisis. In several of these economies - South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong China - aggregate manufacturing employment over the 1990s actually declined. Only in Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand was there a definite upward trend to such employment.

Thus, while female employment in manufacturing was important, the trend over the 1990s, even before the crash, was not necessarily upward. In most of the countries mentioned, there is a definite tendency towards a decline in the share of women workers in total manufacturing employment over the latter part of the 1990s. In Hong Kong and South Korea, the decline in female employment in manufacturing was even sharper than that in aggregate employment. Similarly, even in the countries in which aggregate manufacturing employment increases over the period 1990-97, the female share had a tendency to stabilise or even fall. Thus, in Indonesia the share of women workers in all manufacturing sector workers increased from an admittedly high 45 per cent to as much as 47 per cent by 1993, and then fell to 44 per cent by 1997. In Malaysia the decline in female share was even sharper than in South Korea : from 47 per cent in 1992 to only 40 per cent in 1997. A slight decline was evident even in Thailand.

This fall in women’s share of employment is evident not just for total manufacturing but even for export-oriented manufacturing, and is corroborated by evidence from other sources. Thus Joekes [1999] shows that the share of women employed in EPZs declined even between 1980 and 1990 in Malaysia, South Korea and the Philippines, with the decline being as sharp as more than 20 percentage points (from 75 per cent to only 54 per cent) in the case of Malaysia.

The evidence suggests that the process of feminisation of export employment really peaked somewhere in the early 1990s (if not earlier in some countries) and that thereafter the process was not only less marked, but may even have begun to peter out. This is significant because it refers very clearly to the period before the effects of the financial crisis began to make themselves felt on real economic activity, and even before the slowdown in the growth rate of export production. So, while the crisis may have hastened the process whereby women workers are disproportionately prone to job loss because of the very nature of their employment contracts, in fact the marginal reliance on women workers in export manufacturing activity (or rather in the manufacturing sector in general) had already begun to reduce before the crisis.

In the subsequent period, manufacturing has tended to occupy a much less significant position in total employment of women. In Malaysia the share of women workers in manufacturing to all employed women fell from its peak of 31 per cent in 1992 to 26 per cent in 1999; in the Philippines from 13.3 per cent in 1991 to less than 12 per cent in 1999; in South Korea from its peak of 28 per cent in 1990 to 17 per cent in 2000; and in Hong Kong China from 32 per cent in 1990 to 10 per cent in 1999. [3]

In any case, the nature of such work has also changed in recent years. Most such work was already based on short-term contracts rather than permanent employment for women; now there is much greater reliance on women workers in very small units or even in home-based production, at the bottom of a complex subcontracting chain. Already this was a prevalent tendency in the region. For example, labour flexibility surveys in the Philippines have shown that the greater is the degree of labour casualisation, the higher is the proportion of total employment consisting of women and the more vulnerable these women are to exploitative conditions. [ILO 1995] This became even more marked in the post-crisis adjustment phase. [Pabico 1999]

In Southeast Asia, women have made up a significant proportion of the informal manufacturing industry workforce, in garment workshops, shoe factories and craft industries. Many women also carry out informal activities as temporary workers in farming or in the building industry. In Malaysia, over a third of all electronics, textile and garments firms were found to use sub-contracting. In Thailand, it has been estimated that as many as 38 per cent of clothing workers are homeworkers and the figure is said to be 25-40 percent in the Philippines [Sethuraman 1998]. Home-based workers, working for their own account or on a subcontracting basis, have been found to make products ranging from clothing and footwear to artificial flowers, carpets, electronics and teleservices. [Carr and Chen, 1999; Lund and Srinivas 2000]

This is of course part of a wider international tendency of somewhat longer duration : the emergence of international suppliers of goods who rely less and less on direct production within a specific location and more on subcontracting a greater part of their production activities. Thus, the recent period has seen the emergence and market domination of “manufacturers without factories”, as multinational firms such as Nike and Adidas effectively rely on a complex system of outsourced and subcontracted production based on centrally determined design and quality control. It is true that the increasing use of outsourcing is not confined to export firms; however, because of the flexibility offered by subcontracting, it is clearly of even greater advantage in the intensely competitive exporting sectors and therefore tends to be even more widely used there. Much of this outsourcing activity is based in Asia, although Latin America is also emerging as an important location once again. [Bonacich et al., 1994] Such subcontracted producers in turn vary in size and manufacturing capacity, from medium-sized factories to pure middlemen collecting the output of home-based workers. The crucial role of women workers in such international production activity is now increasingly recognised, whether as wage labour in small factories and workshops run by subcontracting firms, or as piece-rate payment based homeworkers who deal with middlemen in a complex production chain. [Beneria and Roldan, 1987; Mejia, 1997]

A substantial proportion of such subcontracting in fact extends down to homebased work. Thus, in the garments industry alone, the percentage of homeworkers to total workers was estimated at 38 per cent in Thailand, between 25-29 per cent in the Philippines, 30 per cent in one region of Mexico, between 30-60 per cent in Chile and 45 per cent in Venezuela. [Chen, Sebstad and O'Connell, 1998] Home-based work provides substantial opportunity for self-exploitation by workers, especially when payment os on a piece-rate basis; also these are areas typically left unprotected by labour laws and social welfare.

In addition, even other paid work performed by women has become less permanent and more casual or part-time in nature. In South Korea, one of the few countries for which such data is available, the proportion of employed women who casual contracts nearly doubled between 1990 and 1999; over the 1990s, around 60 per cent of all casual jobs were held by women workers.

Not only did paid employment conditions deteriorate in the region of women workers, but unpaid homework also tended to involve longer hours as the post-crisis adjustment process led to cuts in the provision of and access to public services. Only in China did paid employment for women workers, including in manufacturing, continue to grow – but even in China, services employment dominated in total employment for women, at more than 35 per cent. Gender wage gaps have narrowed slightly in most countries in the region, but they remain very high compared to other regions of the world.

Gendered migration patterns in Asia

Asia has become one of the most significant regions in the world not only in terms of the cross-border movement of capital and goods, but also in terms of the movement of people. Asian migration is not a new phenomenon historically, but in the last two decades, more women have moved than ever before. Within the Asian region, there is a complex and changing mix of countries of origin, destination and those that are both. The dominantly labour-sending countries in all of Asia include Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. The countries that are mainly destinations of host countries for migrant labour include all of those in the Middle East, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan China. Some countries are both sending and receiving international migrants: India, Malaysia, Pakistan and Thailand. Obviously, migration is a multidimensional phenomenon, which can have many positive effects because it expands the opportunities for productive work and leads to a wider perspective on many social issues. But it also has negative aspects, dominantly in the nature of work and work conditions and possibilities for abuse by employers and others.

Cross-border migration in Asia is highly gendered, with women migrants largely found in the service sector, especially in the domestic and care sectors, as well as in entertainment work. Male migration by contrast tends to be more in response to the requirements of industrialisation, in construction and manufacturing, as well as in semi-skilled services. Economic considerations are of course the primary reason for migration by individuals, especially women; but when this is large enough in sheer numbers, it has a substantial macroeconomic impact. Remittance incomes from migrant workers have shored up the balance of payments over the past decade in India and Philippines, to name just two countries. It is worth noting that female migrant workers are less affected by business cycle phenomena in the host countries, because of the different nature of activities in which they tend to be employed; therefore, both female migration and remittances from such migration have in general been more stable than the male versions in the recent period.

However, despite the growing significance of female migration in the region, there is little recognition by officialdom in the relevant Asian governments of this process, in terms of ensuring decent working conditions and remuneration for migrants.

Over the past decades, women migrants have come dominantly from three countries in Asia: the Philippines, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. In the Philippines, women migrants have outnumbered their male counterparts since 1992, and in all these countries women are between 60 to 80 per cent of all legal migrants for work. The majority are in services (typically low paid domestic service) or in entertainment work. While Filipino women tend to travel all over the world, women from the other two countries go dominantly to the Middle East and Gulf countries in search of employment. Elsewhere in the region, restrictive regulations have reduced legal female emigration, but may have increased illegal migration, or trafficking.

Migrants typically tend to fill unskilled, labour-intensive and low-paid jobs, and are generally unprotected by labour laws. While male migrants in the region are usually (but not exclusively) in the 3-D occupations (difficult, dirty, dangerous), women migrant workers tend to be concentrated in the low paid sectors of the service industry, in semi-skilled or low-skilled activities ranging from nursing to domestic service, or in the entertainment, tourism and sex industries where they are highly vulnerable and subject to exploitation. They rarely have access to education and other social services, have poor and inadequate housing and living conditions. When they are illegal or quasi-legal and dependent upon contractors, they also find it difficult to avail of existing facilities such as proper medical care and are almost never found to organise to struggle for better conditions. In general, host governments are less than sympathetic to the concerns of migrant workers, including women, despite the crucial role they may play in the host economy. Host country governments tend to view migrants as threats to political and social stability, additional burdens on constrained public budgets for social services and infrastructure, and potential eroders of local culture.

This is why there is so little attempt across the region to ensure decent conditions of migrants, even in terms of ensuring their basic safety and freedom from violence. This is an important issue for women migrants in particular, since they are specially vulnerable to sexual exploitation, not only when they are workers in the entertainment and sex industries, but also when they are employed in other service activities or in factories as cheap labour.

There is often a fine line between voluntary migration and trafficking in women (and girl children). Trafficking is a widespread problem which is on the increase, not only because of growing demand, but also because of larger and more varied sources of supply given the increasingly precarious livelihood conditions in many rural parts of Asia.

A substantial amount of trafficking of both women and children occurs not only for commercial sex work, but also for use as slave labour in factories and other economic activities such as domestic or informal service sector work. It is true, of course, that the worst and most abusive forms of trafficking are those which relate to commercial sexual exploitation and child labour in economic activities. Nor is it the case that trafficking occurs mainly through coercion or deception: there is significant evidence to indicate voluntary movement by the women themselves, especially when home conditions are already oppressive or abusive, or at least voluntary sending by the households of such individuals, given the poverty and absence of economic opportunities in the home region. Traffickers throughout Asia lure their victims by means of attractive promises such as high paying jobs, glamorous employment options, prosperity and fraudulent marriages. When there is employment, however badly paid, precarious and in terrible conditions, it may still be preferred to very adverse home circumstances. This in turn means that those who are employed through trafficking may not always desire to return home, if the adverse economic and social persist. Also, the possibilities of return to home communities with safety and dignity are often limited, given the possibilities of being stigmatised and not easily reintegrated into the home society.

All this makes the problem of dealing with trafficking much more complex than is generally appreciated. From the point of view of attacking the causes, it is important to address the issues of economic vulnerability, marginalization and attitudes to women, which encourage such movement. Environmental disasters and development-induced risks such as displacement are also known to play a role in increasing the incidence of trafficking.

Obviously, across the region there is need for more pro-active policies regarding migration. It is unfortunate that most government policies with respect to migration are designed with the male breadwinner model in mind, because this effectively excludes women, especially those who are trafficked, from the purview of regulation and protection by law. Very easy immigration policies can create routes for easier trafficking; but conversely, tough immigration policies can drive such activities underground and therefore make them even more exploitative of the women and children involved. The specificities and complexities of the trafficking processes, as well as the economic forces that are driving them, need to be borne in mind continuously when designing the relevant policies. Across the region, there is hardly any host country legislation specifically designed to protect migrant workers, and little official recognition of the problems faced by women migrants in particular. The same is true for the sending countries, which accept the remittances sent by such migrants, but without much fanfare or gratitude, and with little attempt to improve the conditions of these workers in the employment abroad. Women migrants, who typically are drawn by the attraction of better incomes and living conditions or by very adverse material conditions at home, are therefore is a no-woman’s land characterised by a generalised lack of protection.

Recently there is also a trend for increased migration by more educated women workers, in the software and IT-enabled service sectors. While such female migration is still a very small part of the total, it is pointing to a different tendency with different implications both for work patterns and for gender relations in both sending and receiving countries.

Conclusion

The picture of women’s employment and migration in Asia today is much more complex than it has appeared for some time. There have been some clear gains from the relatively short-lived process of using much more women’s labour in the greater export-oriented production of the region. One important gain is the social recognition of women’s work, and the acceptance of the need for greater social protection of women workers. The fact of greater entry into the paid work sphere may have also provided greater recognition of women’s unpaid household work. At the same time, however, such unpaid work has tended to increase because of the reduction of government expenditure and support for many basic public services, especially in sanitation, health and care-giving sectors. Recent reversals in the feminisation of employment also point to the possibility of regression in terms of social effects as well. Already, we have seen the rise of revivalist and fundamentalist movements across the Asian region, which seek to put constraints upon the freedom of women to participate actively in public life. This process is not new to capitalism: in the United States, women were actively encouraged to participate in paid work to fill in for labour shortages created by the war during the second World War, only to be thrust back into unpaid household work almost immediately once the war was over. However, the speed and extent of the equivalent processes in Asia still have the capacity for creating major social changes which can have destabilising effects on gender relations and on the possibilities for the empowerment of women generally. At the same time, advances in communication technology and the creation of the “global village” provide both threats and opportunities. They encourage adverse tendencies such as the commodification of women along the lines of the hegemonic culture portrayed in international mass media controlled by giant US-based corporations, and the reaction to that in the form of restrictive traditionalist tendencies. But the sheer knowledge of conditions and possibilities elsewhere can have an important liberating effect upon women, which should not be underestimated.

References

Asis, Maruja M. B. [2003] “Asian women migrants: Going the distance, but not far enough”, mimeo

Beneria, L., and M. Roldan [1987], The Crossroads of Class and Gender: Homework Subcontracting and Household Dynamics in Mexico City, Chicago, University of Chicago Press

Bonacich et al, (eds) Global Production: The Apparel Industry in the Pacific Rim, Temple University Press: Philadelphia.

Carr, Marilyn and Martha Alter Chen [1999] “Globalisation and home-based workers”, WIEGO Working Paper No. 12.

Ghosh, Jayati [1999b] “Trends in economic participation and poverty of women in the Asia-pacific region”, UN-ESCAP Bangkok, also available at website http://www.macroscan.com

Ghosh, Jayati and C. P. Chandrasekhar [2001] Crisis as Conquest: Learning from East Asia, New Delhi: Orient Longman.

Ghosh, Jayati and C. P. Chandrasekhar (eds) [2003] Work and well being in the age of finance, New Delhi: Tulika Books.

Ghosh, Jayati [2003a] “Where have the manufacturing jobs gone? Production, accumulation and relocation in the world economy” in Ghosh and Chandrasekhar (eds).

Ghosh, Jayati [2003b] “Globalisation, export-oriented employment for women and social policy: A case study of India” in Shahra Razavi and Ruth Pearson (eds) Gender and export employment, Palgrave

Harrison, Bennett and Maryellen Kelley [1999] "Outsourcing and the search for flexibility: The morphology of contracting out in US manufacture," in Pathways to Industrialization and Regional Development in the 1990s, Boston, Unwin and Hyman.

Heyzer, Noeleen, ed [1988] Daughters in Industry: Work Skills and Consciousness of Women Workers in Asia, Asia and Pacific Development Centre, Kuala Lumpur

Horton, Susan, ed [1995] Women and Industrialisation in Asia, London : Routledge

ILO [1995] "Women at work in Asia and the Pacific - Recent trends and future challenges", in Briefing Kit on Gender Issues in the World of Work, Geneva

Joekes, Susan [1999] “A gender-analytical perspective on trade and sustainable development”, Trade, Gender and Sustainable Development, UNCTAD, Geneva.

Joekes, Susan and Ann Weston [1994] Women and the New Trade Agenda, UNIFEM, New York

Kibria, Nazli [1995] "Culture, social class and income control in the lives of women garment workers in Bangladesh", Gender and Society, Vol 9 No 3, June, pp 289-309

Korean Working Women’s Network [1998] “Organisational strategies pf irregular women workers”, Seoul, available at http://www.kwwnet.org.

Lee, Hyehoon [2001] “Evaluation and promotion of social safety nets for women affected by the Asian economic crisis”, Expert Group Meeting on Social Safety Nets for Women, UNESCAP, Bangkok

Lim, Lean Lin [1994] "Women at work in Asia and the Pacific: recent trends and future challenges", Paper for International Forum on Equality for Women in the World of Work, Geneva, ILS

Lim, Lin Lean [1996] More and Better Jobs for Women : An action guide, ILO Geneva

Malapit, Hazel Jean [2001] “A review of literature on gender and trade in Asia”, Asian Gender and Trade Network, www.genderandtrade.org.

Mejia, R. [1997] “The impacy of globalisation on women workers”, in The Impact of Globalisation on Women Workers : Case Studies from Mexico, Asia, South Africa and the United States, Oxfam.

Meng, Xin [1998] “The economic position of women in Asia”, CLARA Working Paper No. 4, Amsterdam

Rayanakorn, Kobkun [2002] “Gender inequity”, mimeo

Tullao, Teresa and Michael Angelo Cortez [2003] “Movement of natural persons and its human development implications in Asia”, UNDP mimeo.

Wee, Vivienne (ed) [1998] Trade liberalisation: Challenges and opportunities for women in Southeast Asia, UNIFEM and ENGENDER, New York and Singapore

[1] This

question has been considered in detail in Ghosh

(2003a), which examines patterns of manufacturing

employment in the most “dynamic” developing

country exporters over the 1990s.

[2] The discussion that follows is based on a more detailed consideration in Ghosh (2003b).

[3] Data from ILO: KILM 2002.

[2] The discussion that follows is based on a more detailed consideration in Ghosh (2003b).

[3] Data from ILO: KILM 2002.

© MACROSCAN

2003