Changes in the World of Work

Global Economic Processes

There are at least six recent processes in the international economy that have a direct bearing upon labour markets and work conditions in countries across the world. The first, and possibly the most important, is the fact that the world economy is operating substantially below capacity. The global unemployment equilibrium is actually getting more severe, because of the deflationary impulse imparted by the domination of finance capital and the inadequate role played by the US as 'leader' of the world economy.

This is especially noteworthy because the US administration is otherwise exerting itself to impose newly aggressive and militaristic imperialism upon the rest of the world. The US is not currently fulfilling its role (in the Kindleberger sense) of leader of the world economy to maintain stability. Such a role requires the fulfilment of three functions at a minimum: discounting in crisis; counter-cyclical lending to countries affected by private investors' decisions; and providing a market for net exports of the rest of the world, especially those countries requiring it to repay debt. The absence of discounting in crisis is not universal; there are countries that have received large bail-outs orchestrated by the US Treasury and the IMF. But the spectacular collapse of Argentina, the bleeding of Sub-Saharan Africa despite impending large-scale famine, and the indifference to implosions in Eastern Europe and elsewhere, bear witness to the fact that the US administration does not see its responsibility to discount in crisis, in terms of salvaging the larger system.

Similarly, counter-cyclical lending has been discouraged, as private finance (including portfolio capital) has been associated with creating sharp boom-and-bust cycles rather than mitigating them, and US policy has been geared towards protecting such behaviour rather than repressing it. Finally, while the US did play a crucial role as an engine of world trade by running very large external trade deficits in the 1990s, that role has been much diminished after 2000. Indeed, even before then, the import surplus in the US reflected private investment-savings deficits, as the government's budgetary role became more contractionary.

Partly because of this inadequately accepted role of the leader, and partly because of the deflationary impulse provided by the greater mobility of finance capital, aggregate growth in the world capitalist system has been far below expectations, especially in the recent phase. It is now clear that the period has been associated with a deceleration of economic activity in much of the developed world, a continuing implosion in vast areas of the developing world including the continent of Africa, and a dramatic downslide in what had hitherto been the most dynamic segment of the world economy-East and Southeast Asia. These processes are reflected in decelerated rates of growth of world trade (in value terms) despite the enforced liberalization of trade in most countries, as well as in declining rates of greenfield investment across the world. Even as most economies remain in the grip of recession or even the possibility of deflation, counter-cyclical or expansionary macroeconomic policies remain out of reach for governments because of a combination of fear of the power of finance and domination of the neoliberal economic policy approach.

Second, corporate globalization has been marked by greatly increased disparities, both within and between countries. While there is-inevitably-a debate over this, most careful studies find increased inequality within and across regions[1] as well as a stubborn persistence of poverty and a marked absence of the 'convergence' predicted by apologists of the system. In addition, the bulk of the people across the world find themselves in more fragile and vulnerable economic circumstances in which many of the earlier welfare state provisions have been reduced or removed, and public services have been privatized or made more expensive and therefore less accessible. This has not only affected the socio-economic rights of citizens, it has also added to the problem of inadequate effective demand and therefore contributed to recessionary tendencies worldwide.

Such inequalities are only likely to be intensified by the third process exemplified by recent patterns of international capital flows. For the last four years, there has been a net transfer of resources from the less developed countries to the developed North, and particularly to the United States. This peculiar, even appalling, result indicates the way in which international flows of money increasingly reflect the international distribution of power, with private citizens and central banks of the developing world (especially in Asia) choosing to hold their savings and foreign exchange reserves in the safe havens of the North. The United States economy (and, of course, US Treasury Bills in particular) remain, the most favoured destination for investors across the world. But even the recent partial flight from the dollar has generally had the effect of strengthening European financial assets rather than flowing to developing economies that are in need of such resources. Indeed, the paradox is such that the developing countries that could most profitably use these capital resources are imposing deflationary policies at home, which create excess capacity and inadequate demand, and make the export of capital appear to be more attractive. The United States attracted 70 per cent of the world's savings over the last two years; even after the supposed 'revulsion' from dollar assets in the last year, it continues to attract at least half of the rest of the world's savings.

The fourth feature is also related to the mobility of capital and the domination of finance. Developing countries in general, and semi-industrial 'emerging markets' in particular, experience much greater economic and financial volatility because of their exposure to boom-and-bust cycles created by rapid and unsustained capital flows of relatively large magnitudes. There is therefore much greater vulnerability to capital account-driven external shocks, even as the role of domestic counter-cyclical macroeconomic policies has been greatly diminished by the fear of further capital flight and the hegemony of the neoliberal economic policy paradigm. By the end of 2001, it was estimated that there had been more than 67 currency crises in emerging markets over the previous decade. The only reason that such crises have been somewhat less in evidence since then, is because private capital markets have actually dried up vis-à-vis the developing countries, and net flows positive into most emerging markets are no longer. (India is of course currently an exception, receiving relatively large inflows of portfolio capital which are simply adding to the external reserves of the country and are therefore extremely expensive for the government to allow.)

The fifth feature is the growing concentration of ownership and control in the international production and distribution of goods and services, and also among the agents of international finance. It is no secret that the decade of globalization has been marked by some of the strongest and most sweeping waves of concentration of economic activity that we have known historically. Periods of high concentration are also periods of intensification of competitive pressures. Intensification of competition in turn means that the 'normal' tendencies of capitalist accumulation are sharpened and aggravated, including the pressure to find more and more means of reducing labour costs, for example. Concentration also involves the amalgamation or destruction of smaller capitals. The very process of the big swallowing up the small, at both national and international levels, tends to reduce employment. So the reorganization and restructuring of production takes the form of a decline in importance of smaller, more employment-intensive manufacturing units and the growing dominance of large players employing much fewer people. Associated with this are the well-known stagnationist tendencies of monopoly capital, which also tend to indirectly reduce employment through their effect on aggregate demand. Crises in emerging markets are typically associated with further concentration, as the attempt to resolve such crises within the basic neoliberal paradigm has involved further liberalization and privatization, thus allowing the sale of domestic business units to large multinationals.

One very recent feature deserves to be noted: the apparent breakdown of multilateralism. While the collapse of the WTO negotiations in Cancun has been ascribed to a group of developing countries, the truth is that the intransigence, refusal to admit past transgression and reluctance to negotiate on the part of the developed countries was instrumental in creating the deadlock. The implementation of the 1994 GATT agreement and the functioning of the WTO have already been heavily skewed in favour of the interests of developed countries, particularly the United States. Nevertheless, the Bush administration has clearly shown that it has scant regard for international institutions, which it uses only when they explicitly serve its own immediate ends. The US government's attitude towards the WTO has been similar in that it has been unwilling to make even the smallest compromise to an international institution that has already been biased towards the US in its functioning. The current decline in multilateralism is likely to herald a period of greater uncertainty and fluidity in world trade, as well as a scramble for bilateral and regional deals and pressure for competitive devaluations. While this may appear to reduce the power of developing countries, it is worth remembering that in the past century, such periods in the world economy have been precisely those when today's semi-industrial economies could achieve some amount of autonomous industrialization.

Changes in Labour Markets

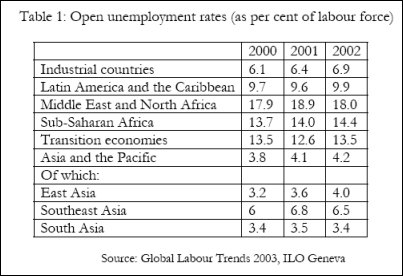

These broader changes in the international economy have also affected national and international labour markets. The most significant change is the increase in open unemployment rates across the world. By the turn of the century, unemployment rates in most industrial countries were higher than they had been at any time since the Great Depression of the 1930s. But even more significantly, open unemployment was very high in the developing countries, and has continued to grow thereafter, as Table 1 indicates. This marks a change, because developing countries typically have had lower open unemployment rates simply because of the lack of social security and unemployment benefits in most such societies, which ensures that people undertake some activity, however low-paying, and usually in the form of self-employment. Therefore disguised unemployment or underemployment has generally been the more prevalent phenomenon in developing societies. The recent emergence of high open unemployment rates therefore suggests that the problem of finding jobs has become so acute that it is now captured even in such data, and may also herald substantial social changes in the developing world.

|

|

The

Asian region typically has the lowest rates of open unemployment in the

world, but even here, as can be seen from Table 1, these rates have been

historically high and rising, especially in Southeast Asia. This extensive

slack in labour markets across the world is a direct reflection of the

global recessionary tendency that has already been discussed above, and

all the evidence suggests that this slack has been increasing in recent

years, as economies even in the developing world continue to operate far

below potential. Furthermore, in most Asian countries, youth unemployment

is especially high.

In many Asian economies, moreover, underemployment continues to be a

significant concern. This is especially true in Southeast and South Asia.

In Nepal underemployment is officially estimated to be as high as half the

work force, while in Indonesia and the Philippines disguised unemployment

is high and rising, especially in the informal sector.

Another very significant change in the recent past is the decline in

formal-sector employment. Once again, this is a trend that is spread

across the globe and covers both developed and developing countries. In

developing countries, the substantial reduction in the share of

organized-sector employment has been associated not only with increased

open unemployment but also the proliferation of workers crowded into the

informal sector, and typically more in the low-wage, low-productivity

occupations that are characteristic of 'refuge sectors' in labour markets.

While there are also some high value-added jobs increasingly in the

informal sector (including, for example, computer professionals and some

high-end IT-enabled services), these are relatively small in number and

certainly too few to make much of a dent in the overall trend, especially

in countries where the vast bulk of the labour force is unskilled or

relatively less skilled. In turn, this has meant that the cycle of

poverty–low employment generation–poverty has been accentuated because of

the diminished willingness or ability of developing country governments to

intervene positively for expanded employment generation.

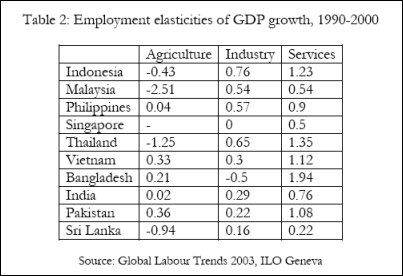

The decline in employment elasticities of production is a tendency that is

especially marked in developing countries. To some extent, this reflects

the impact of international concentration of production and export

orientation, as the necessity of making products that will be acceptable

in world markets requires the use of new technologies developed in the

North and inherently labour-saving in nature. But what is interesting is

the extent to which declining employment elasticities in developing Asia

have marked all major productive sectors, including agriculture. This is

evident from Table 2, which describes the employment elasticity of GDP

growth in the major productive sectors over 1990–2000 in the major

economies of Southeast and South Asia. Agriculture is clearly no longer a

refuge sector for those unable to find employment elsewhere-the data

indicate low or even negative employment elasticity in this sector,

reflecting a combination of labour-saving technological changes such as

greater use of threshers and harvesters, and changes in landholding

patterns resulting in lower extents of traditional small peasant farming

because of the reduced economic viability of smallholder cultivation

across the region. The service sector, by contrast, seems to have emerged

as the refuge sector in this region, except possibly in countries like Sri

Lanka and India.

|

|

The emergence of global production chains is another important feature of

the recent past. These are not entirely new, and even the current chains

can be dated from at least the 1980s. However, two major sets of changes

have dramatically increased the relocation possibilities in international

production. The first set includes technological changes, which have

allowed for different parts of the production process to be split and

locationally separated, as well as created different types of requirement

for labour involving a few highly skilled professional workers and a vast

bulk of semi-skilled workers for whom burn-out is more widely prevalent

than learning by doing. The second set includes organizational changes

which are associated with concentration of ownership and control, but also

with greater dispersion and more layers of outsourcing and subcontracting

of particular activities and parts of the production process.

Therefore, we now have the emergence of international suppliers of goods

who rely less and less on direct production within a specific location and

more on subcontracting a great part of their production activities. Thus

the recent period has seen the emergence and market domination of

'manufacturers without factories', as multinational firms such as Nike and

Adidas effectively rely on a complex system of outsourced and

subcontracted production based on centrally determined design and quality

control. This has been strongly associated with an increase in

export-oriented production in manufacturing in a range of developing

countries, especially in textiles and garments, computer hardware,

consumer electronics and related sectors. It is true that the increasing

use of outsourcing is not confined to export firms; however, because of

the flexibility offered by subcontracting, it is clearly of greater

advantage in the intensely competitive exporting sectors and therefore

tends to be more widely used there.

Much of this outsourcing activity is based in Asia, although Latin America

is emerging as an important location once again. Such subcontracted

producers vary in size and manufacturing capacity, from medium-sized

factories to pure middlemen collecting the output of home-based workers.

The crucial role of women workers in such international production

activity is now increasingly recognized, whether as wage labour in small

factories and workshops run by subcontracting firms, or as piece-rate

payment-based home workers who deal with middlemen in a complex production

chain.

Finally, there is the very significant effect of international migration,

in determining changes in both national labour markets and macroeconomic

processes within home and host countries. In Latin America, migration is a

response to the lack of productive employment opportunities within the

country-at least 15 per cent of the labour force of most Central American

countries (in particular, El Salvador, Guatemala and the Honduras) is

estimated to be working in the United States, mostly in underpaid,

oppressive and precarious jobs. Migration flows are especially marked for

Asia over the last two decades, and within the broad Asian region. South

Asian migrant workers in the Gulf and West Asia have contributed huge

flows of remittance income which has stabilised the current account in

India and Bangladesh, for example. Within Southeast Asia, Thailand is host

to approximately 890,000 migrant workers, while Malaysia is estimated to

have more than 900,000 on official count. In Singapore, one quarter of the

work force is comprised of migrants. Typically, of course, such migrants

are used for 3-D jobs ('difficult, dirty and dangerous') as well as in

unskilled sectors. In Malaysia, for example, 70 per cent of the unskilled

construction workers come from Indonesia. What is noteworthy about Asian

migration is the significant role played by women migrants, especially

from the Philippines but also from other parts of the continent. It should

be noted, of course, that the line between voluntary migration and

trafficking is often quite thin.

Emerging

Processes

There are a number of important processes

currently at work, which will shape national, regional and international

labour markets in the near future. The first is a process that is still

unfolding, and is likely to have possibly seismic effects on patterns of

work across the world-the demographic shifts and consequent

imbalances in population structure as between industrial and developing

countries.

The ageing population structure of most industrial societies, and even

some developing countries in the western hemisphere, implies that by the

next decade of this century, many activities will effectively have to be

outsourced to other regions, whether through labour migration or through

devices made possible by new technology, such as IT-enabled services. By

2010, it is estimated that nearly 60 per cent of the world's labour force

will be in Asia, which still has a dominantly young population. This is

surely likely to have profound implications for patterns of development

and for labour markets, which are still inadequately comprehended.

The current crisis in developing country agriculture and the growing

problems of even subsistence farming are also likely to have major

implications, not only for the present, with agrarian crisis becoming a

standard feature of most developing economies, but also for the future. It

is in this context that the overall inadequacies of employment generation

in other sectors become even more problematic. The breakdown of

traditional Lewis-type mechanisms of moving labour from agriculture to

other more dynamic sectors, in a context in which global integration of

distorted agricultural markets is making even traditional subsistence

cultivation difficult if not unviable, is likely to make employment the

single most important social issue in almost all developing societies in

the near future.

Two other issues,

which have recently attracted a lot of discussion, deserve to be

considered in more detail. The

first

relates to

the perception widespread in the North, that manufacturing jobs are being

exported from North to South. The

second is the

issue of feminization of work,

especially export-oriented work, in the developing world.

The last

decade has seen a significant shift in the structure of international

manufacturing production, such that developing countries now account for

nearly a quarter of the world's manufacturing goods exports, up from just

over one-tenth two decades ago. Such relocation, which in turn is supposed

to imply a net loss of manufacturing jobs in the North and a net expansion

of such jobs in the South, has been seen as being driven by both the

movement of capital, as multinational companies in particular move to

areas characterized by cheaper labour, and trade liberalization, which has

allowed manufactured goods produced in Southern locations to penetrate

Northern markets.

In actual fact, however, there is little evidence of the 'export' of

manufacturing jobs.[2]The

vast majority of developing countries have experienced very substantial

losses in manufacturing employment as a result of the liberalization of

trade and financial markets. Even the top thirteen developing country

exporters (excluding China) do not show increases in manufacturing

employment. So, while such jobs may have declined in the North, they have

not increased commensurately in the South, even in the group of most

dynamic developing country exporters. This is because trade liberalization

has meant loss of many manufacturing jobs in developing countries to

imports even as some jobs may have increased through exports, and because

technological changes in both the North and the South have given rise to

low and declining employment elasticities of manufacturing production.

These factors in turn stem from a larger process of national and

international concentration of production, intensification of competitive

pressure and the greater power of large capital. These have accelerated

the adoption of labour-saving technology, encouraged flexible labour

market practices, adversely affected small manufacturing enterprises, and

induced a deflationary policy bias into most economies. All of these have

impacted adversely on employment, leading to the 'disappearance' of

manufacturing jobs, rather than their export.

Another common perception relates to the fact that the increasing

importance of export-oriented manufacturing activities in many developed

countries has been associated with a much greater reliance on women's paid

labour. This process was most marked over the period 1980 to 1995 in the

high-exporting economies of East and Southeast Asia, where the share of

female employment in total employment in the export processing zones (EPZs)

and export-oriented manufacturing industries typically exceeded 70 per

cent. It was also observed in a number of other developing countries, for

example in Latin America, in certain types of export manufacture.

Women workers were preferred by employers in export activities primarily

because of the inferior conditions of work and pay that they were usually

willing to accept. Women workers had lower reservation wages than their

male counterparts, were more willing to accept longer hours and

unpleasant, often unhealthy or hazardous, factory conditions, typically

did not unionize or engage in other forms of collective bargaining to

improve conditions, and did not ask for permanent contracts. They were

thus easier to hire and fire at will and according to external demand

conditions, and also, life-cycle changes such as marriage and childbirth

could be used as proximate causes to terminate employment. Another

important reason for feminization was the greater flexibility afforded by

such labour for employers, in terms of less secure contracts. Further, in

some of the newer 'sunrise' industries of the period, such as the computer

hardware and consumer electronics sectors, the nature of the assembly-line

work-repetitive and detailed, with an emphasis on manual dexterity and

fineness of elaboration-was felt to be especially suited to women. The

high 'burn-out' associated with some of these activities meant that

employers preferred work forces that could be periodically replaced, which

was easier when the employed group consisted of young women who could move

on to other phases of their life-cycle.

The feminization of such activities had both positive and negative effects

for the women concerned. On the one hand, it definitely meant greater

recognition and remuneration of women's work, and typically improved the

relative status and bargaining power of women within households, as well

as their own self-worth, thereby leading to empowerment. On the other

hand, it is also true that most women are rarely if ever 'unemployed' in

their lives, in that they are almost continuously involved in various

forms of productive or reproductive activities, even if they are not

recognized as 'working' or paid for such activities. This means that the

increase in paid employment may lead to an onerous double burden of work

unless other social policies and institutions emerge to deal with

the work traditionally assigned to (unpaid) women.

Given these features, it has been fairly clear for some time now that the

feminization of work need not be a cause for unqualified celebration on

the part of those interested in improving women's material status.

However, it is now becoming evident that the process of feminization of

labour in export-oriented industries may have been even more dependent

upon the relative inferiority of remuneration and working conditions than

was generally supposed. This becomes very clear from a consideration of

the pattern of female involvement in paid labour markets in East and

Southeast Asia, and more specifically in the export industries, over the

entire 1990s. What the evidence suggests is that the process of

feminization of export employment really peaked somewhere in the early

1990s (if not earlier in some countries), and that thereafter the process

was not only less marked but may even have begun to peter out. This is

significant because it refers very clearly to the period before the

effects of the financial crisis began to make themselves felt on real

economic activity, and even before the slowdown in the growth rate of

export production. So, while the crisis may have hastened the process

whereby women workers are disproportionately prone to job loss because of

the very nature of their employment contracts, in fact, the marginal

reliance on women workers in export manufacturing activity (or rather, in

the manufacturing sector in general) had already begun to reduce before

the

crisis.

[3]

A reversal of the process of feminization of work has already been

observed in other parts of the developing world, notably in Latin America.

Quite often, such declines in the female share of employment have been

found to be associated with either one of two conditions: an overall

decline in employment opportunities because of recession or structural

adjustment measures, or a shift in the nature of the new employment

generation towards more skilled or lucrative activities. There could be

another factor. As women became an established part of the paid work

force, and even the dominant part in certain sectors (as indeed they did

become in the textiles, readymade garments and consumer electronics

sectors of East Asia), it became more difficult to exercise the

traditional type of gender discrimination at work. Not only was there an

upward pressure on their wages but also other pressures for legislation

which would improve their overall conditions of work. Social action and

legislation designed to improve the conditions of women workers tended to

reduce the relative attractiveness of women workers for those employers

who had earlier relied on the inferior conditions of women's work to

enhance their export profitability. The rise in wages also tended to have

the same effect. Thus, as the relative effective remuneration of women

improved (in terms of the total package of wage and work and contract

conditions), their attractiveness to employers decreased.

Conclusion

The recent

trends and emerging processes described above point to some very difficult

issues for policy, even as employment generation is becoming the single

most pressing concern in most societies. Quite simply, the basic question

relates to how adequate and decent work is to be ensured for men and women

workers, in an international

context in which greater economic integration has drastically altered the

contours of public policy as well as the requirements of employers. It may

be that policies directed towards labour markets are less effective in

securing desired outcomes; rather, it may be necessary to shift and

reorient basic macroeconomic policies towards more growth and employment

generation in general.

[1]

Cornia, 2001; Milanovic 2002, etc. A more

extensive survey of the literature on

globalisation and inequality is available on

www.networkideas.org.

[2]

This argument is developed and substantiated in

Ghosh "Exporting jobs or watching them disappear?

Relocation, employment and accumulation in the

world economy", in Ghosh and Chadrasekhar (eds)

Work and well-being in the age of finance, Tulika

Books 2002.

[3]

This argument is provided in more detail in Ghosh

"Export-oriented employment of women in India" in

Razavi and Pearson (eds) Social policy and women's

export employment, Macmillan, forthcoming.