Features

24.03.2004

Stock Markets: A Nifty Source for Investment?

On the surface, it could not have been a better financial year for India's stock markets. Providing one of the principal signals for what the government sees as a widespread "feel good" factor, the market has performed extremely well, touching new highs and not nose diving as a result of an inevitable correction. Sustained foreign institutional investor (FII) interest is an obvious explanation. FIIs have reportedly invested an unprecedented $10 billion in the markets this year, with more than a fifth of that amount coming in over the last three months. Clearly, India is the flavour of the season for the international investor. This has contributed in no small measure to the new faith in the markets that is reflected in the media and elsewhere.

However, it needs to be noted that India is still a marginal market globally speaking and even the growing presence of the FIIs has not radically transformed India's relative position among emerging markets in Asia and elsewhere in the world. According to one estimate, the ratio of capitalization in India's markets relative to global market capitalization is estimated to have risen only marginally from 0.6 to 0.8 per cent, when that of emerging Asia has a whole rose from 4.3 to 5.1 per cent. But, given the past and recent history of markets in India, the focus of analysts has been on the more or less sustained nature of buoyancy rather than the cause for it or its significance globally.

The optimism generated by this buoyancy received a boost when the government successfully completed, with large doses of oversubscription, the disinvestment of large chunks of shares in six companies - IBP, CMC, IPCL, Dredging Corporation of India, GAIL and ONGC. This amounted to sale of shares worth in excess of Rs. 14,000 crore, with Rs. 10,500 crore being raised from the sale of ONGC shares alone. Since these shares were not being traded earlier in the market, the disinvestment amounts to mobilisation of new capital through the market, even if not for greenfield investments.

As a

result, India's languishing "primary market" appears to have received a

huge boost. According to figures released by Prime Database (Business

Line March 17, 2004), as compared with a little over Rs.1,000 crore each

mobilised from primary share markets in 2001-02 and 2002-03 and a peak

of Rs.13,300 crore mobilised in 1994-95, the amount mobilised this

financial year (2003-04) amounts to Rs. 17,665 crore (Chart 1). In fact,

even if we take the total additional capital in the form of equity and

debt (shares and debentures) raised from the markets during the 1990s

there were only three years between 1992-93 and 1994-95, when this

year's primary equity market yield was exceeded.

Given this dramatic performance in a single year, the temptation to declare that India's stock markets have reached maturity and finally emerged a major source of capital for investment is indeed great. Even if it was the set of six public issues that helped deliver this result, the argument is likely to persist because specific events are often crucial in changing the tide in markets. For example, a virtually dead stock market till the late 1970s gradually saw an increase in activity largely because of the decision of multinational firms – especially multinational drug companies – to dilute their share in the equity of companies they held. Pressured by the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, which required dilution of the foreign share in equity to the 40 per cent level, multinational firms put on sale large chunks of equity that were sold to buyers in small lots of shares, so as to retain control. This did encourage some retail interest in stock markets, resulting in a reduction in the overwhelming role of the financial institutions and large corporates in the market. The question then is whether the choice of market-mediated disinvestment of large chunks of equity in successful, high-profit, public sector units would change India's stock market scenario. In particular, would this transform India's markets in a manner that would make it easier to mobilise capital for investment directly from saving households in the years to come?

There

are a number of reasons to believe that the answer to that question must

be negative. To start with, nowhere in the world is the stock market a

source of capital for new investment, not even in the US which is home

to some of the best organised and vibrant markets. It is known that in

that country, during the period when financial liberalisation

transformed the financial structure of the country, retained profits of

firms were the principal source of capital for investment. Further, debt

in the form of bank finance and bonds continued to play a more important

role than equity. Thus, between 1970 and 1989, the ratio of profit

retention, bank finance and bonds to the net sources of finance of

non-financial corporations in the US amounted to 91.3, 16.6 and 17.1 per

cent respectively. The contribution of equity was a negative 8.8 per

cent. The first two of these sources played an overwhelming role during

this period in the U.K. and Germany as well, with even bond markets

playing a limited role and equity markets virtually no role at all in

financing corporate investment. More recent evidence suggests that this

scenario persists. The message from those markets is clear: the stock

market is primarily a site to exchange risks rather than raise capital

for investment.

In

India, the experience with equity and debt mobilised from markets as

sources of finance during the 1990s is indeed telling. To start with, as

Chart 5 shows, the ratio of capital mobilised through equity and

debentures to financial assistance disbursed by the financial

institutions has fallen steeply during the latter half of the 1990s.

That is the role of finance from the development financial institutions,

which in volume terms rose from Rs.12,810 crore in 1990-91 to a peak of

Rs. 75,364 crore in 2001-02 (before falling to Rs. 58,735 crore in

2002-03), was not just significant but overwhelming in the latter half

of the decade. This was also the period when a combination of failure

(as in the case of UTI) and policy was preparing the ground for an end

to the era of development finance in India (Refer Macroscan, Business

Line, February 17, 2004).

It was

not just that support from the DFIs was crucial to financing investment

at the margin, but the nature of capital mobilised from the market also

indicates a bias in favour of debt. As Chart 3 shows, in the past, as

during 1992-93 to 1995-96, in years when significant sums of capital

were mobilised, a substantially larger share came from the issue of

equity rather than debentures. If active markets help firms to mobilise

capital through equity issues, that would be the preferred option since

risks are shared with the investor, whereas creditors have to be paid

interest routinely and given precedence in case of liquidation.

Interestingly, however, towards the end of the 1990s and early into the

next decade, when the record with mobilisation of capital from the

markets has been reasonably good, firms have had to rely on debentures

rather than equity. Clearly, investor preference was for debentures

rather than equity, indicating that the capital gains and returns

expected from the latter were overshadowed by the security of the

former.

All this suggests that two features of the remarkable performance of the markets in 2003-04 in terms of delivering new capital against shares that were not previously being traded are of utmost significance. First, the important role of the FIIs in sustaining the boom in markets and in acquiring the shares of the six PSUs that ensured the record capital mobilisation figure. Second, the fact that there was one extremely attractive PSU, namely ONGC, whose share had been put on offer.

Even within days of the opening of the issue of shares of some of these PSUs, the interest of foreign institutional investors was obvious. For example, they accounted for 75 and 55 per cent respectively of the demand for IPCL and CMC shares by February 26, 2004. Therefore, the government's real concern was not with these companies, but with IBP. In the case of that company, the FIIs were not interested at all, accounting for just 2 per cent of total claims. Unfortunately, retail investors, who were important targets of the disinvestment exercise, were not the ones who helped shore up the issue finally, since they accounted for just 6 per cent of demand. The prime role was played by the financial institutions and mutual funds that had come forward to take up 44 and 36 per cent of the demand, at a time when the issue was still not oversubscribed. Given Disinvestment Minister Shourie's alarmist tantrums when the issue was not being responded to, it does appear that the government had "persuaded" the institutions to fill the gap.

Compare this with the performance of the ONGC issue. The sale of 10 per cent of ONGC shares, which was the largest-ever public issue in the country, was fully subscribed within 10 minutes of the opening of the offer. The immediate surge in demand on the first day of the issue came mainly from FIIs who accounted for bids amounting to over Rs 18,000 crore. Retail investors applied for just 13,520 shares, compared with 26.14 crore shares that the FIIs bid for. According to subscription details, FIIs accounted for over 87 per cent of the total bids made on the first day. Finally, the issue was oversubscribed six times. There was a further twist to the story. The media has it that Warren Buffet pumped in around $1 billion to acquire a large chunk of shares.

This kind of interest on the part of the FIIs and by investors like Buffet who virtually "lead the herd", suggests that the pricing of the shares was such that they were so lucrative that the offer could not be refused. Associated with the success of the issue may be, a substantial loss in terms of the value of the assets that the government has given up. There are bound to be questions regarding the price band in which the shares of the different PSUs were offered. It is widely known that given imperfections, prevailing market prices are no indicator of the true value of a financial asset. But even such comparisons are suggestive. There were very few ONGC shares floating in the market, but evidence from the other firms is telling. Thus, IPCL shares were being offered at a floor price of Rs. 170, which was well below the Rs. 195.70 at which the share was being quoted at the National Stock Exchange just before the offer opened. The corresponding figures were Rs. 475 and Rs. 541.50 for CMC and Rs. 620 and 717.75 for IBP.

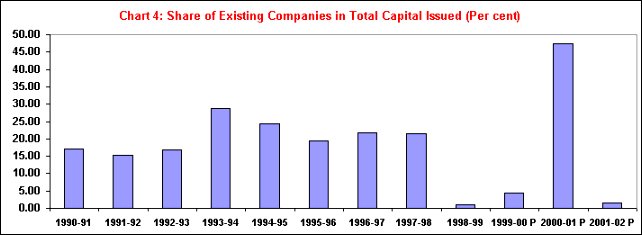

The

figures also make sense in the light of other evidence. One puzzling

feature of the data on mobilisation of capital through the market is

that during the period 1998-99 to 2001-02, the share of new (as opposed

to existing) companies in total capital mobilised was extremely high

(Chart 4). But, these were the years when additional mobilisation occurred

largely through debentures. There seems to be a reversal in 2003-04,

which is clearly a year when mobilisation through equity would overwhelmingly

dominate. Interestingly, that also happens to be a year when the sale

of equity by existing and highly profitable companies would account

for an overwhelming share of the mobilisation. The message therefore

appears clear. The experience of 2003-04 is not one that points to a

transformation of India's stock markets into a cash cow for entrepreneurs

with new investment ideas. It is proof that while the capital market

remains one in which profit hunters trade risks in secondary markets,

there would be periodic primary market booms whenever speculation spills

over into a thirst for even new shares or when the government desperate

to mobilise budgetary resources and/or shore up its "reformist"

image puts on sale the best PSUs, at what are seen as bargain prices.

The entrepreneur with an eye to the small investor's wallet has little

cause to cheer.

© MACROSCAN

2004