Themes > Features

17.03.2004

The End of Development Finance

Close to

two years back, on March 30 2002, the Industrial Credit and Investment

Corporation of India (ICICI) was through a reverse merger, integrated with

ICICI Bank. That was the beginning of a process that is leading to the

demise of development finance in the country. The reverse merger was the

result of a decision (announced

on October 25, 2001) by the ICICI to

transform itself into a universal bank that would engage itself not only

in traditional banking, but also investment banking and other financial

activities. The proposal also involved merging ICICI Personal Financial

Services Ltd and ICICI Capital Services Ltd with the bank, resulting in

the creation of a financial behemoth with assets of more than Rs. 95,000

crore. The new company was to become the first entity in India to serve as

a financial supermarket and offer almost every financial product under one

roof.

Since the announcement of

that decision, not only has the merger been put through, but similar moves

are underway to transform the other two principal development finance

institutions in the country, the Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI),

established in 1948, and the Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI),

created in 1964. In early February, Finance Minister Jaswant Singh

announced the government's decision to merge the IFCI with a big public

sector bank, like the Punjab National Bank. Following that decision, the

IFCI board has approved the proposal, rendering itself defunct.

It is expected that the decision would be implemented despite considerable

scepticism among both PNB shareholders and IFCI employees with regard to

the proposal. On his last day in office, the erstwhile Chairman and

Managing Director of IFCI, V. P. Singh, sought to assuage the fears of PNB

shareholders by saying that IFCI would clear most of its liabilities

before the merger. Freed of them, PNB, in his view, could leverage IFCI's

existing expertise on project financing, monitoring, advisory services and

term-lending to complement its existing business.

Finally,

recently the Parliament has approved the corporatisation of the IDBI,

which had been debated for more than a year, paving the way for its merger

with a bank as well. IDBI had earlier set up IDBI Bank as a subsidiary.

However, the process of restructuring IDBI has involved converting the

IDBI Bank into a stand alone bank, through the sale of IDBI's stake in the

institution. Since there is no clear declaration that IDBI Bank would be

chosen as the partner bank for the proposed merger of the DFI, talk of an

alternative is very much in the air. Among the banks being mentioned are:

Bank of Baroda, Punjab National Bank, Indian Bank and Canara Bank.

When the

bill to corporatise IDBI was put through with some difficulty in the Rajya

Sabha, it appeared that the government had provided two commitments. The

first was that the government would retain a majority stake in the entity

into which the IDBI would be transformed.

The government currently

has a 58.47 per cent stake in IDBI.

And, second that the

development finance emphasis of the institution would be retained. But

already doubts are being expressed about the government's willingness to

stick to the first of these commitments. And once the merger creates a

universal bank as a new entity, with multiple interests and a strong

emphasis on commercial profits, it is unclear how the second commitment

can be met either.

As part of

the corporatisation process, the

IDBI has received a forbearance of five

years with respect to the SLR requirement. It is however ready to meet the

obligation of cash reserve ratio (CRR) of around Rs 2,000 crore to the RBI

immediately. The SLR requirement for the institution is pegged at around

Rs 18,000 crore. The non-performing assets (NPAs) of around Rs 15,000

crore are likely to be transferred out of the institution as and when the

merger with a bank takes place.

These developments on the development banking front do herald a new era.

An important financial intervention adopted by almost all

late-industrialising developing countries, besides pre-emption of bank

credit for specific purposes, was the creation of special development

banks with the mandate to provide adequate, even subsidised, credit to

selected industrial establishments and the agricultural sector. According

to an OECD estimate quoted by Eshag, there were about 340 such banks

operating in some 80 developing countries in the mid-1960s. Over half

these banks were state-owned and funded by the exchequer, the remainder

had a mixed ownership or were private. Mixed and private banks were given

government subsidies to enable them to earn a normal rate of profit.

The principal motivation for

the creation of such financial institutions was to make up for the failure

of private financial agents to provide certain kinds of credit to certain

kinds of clients. Private institutions may fail to do so because of high

default risks that cannot be covered by high enough risk premiums because

such rates are not viable. In other instances, failure may be because of

the unwillingness of financial agents to take on certain kinds of risk, or

because anticipated returns to private agents are much lower than the

social returns in the investment concerned.

In practice, financial intermediaries seek

to tailor the demands for credit from them with their funds by adjusting

not just interest rates, but also the terms on which credit is provided.

Lending gets linked to collateral, and the nature and quality of that

collateral is adjusted according to the nature of the borrower and supply

and demand conditions in the credit market. In the event, depending on the

quantum and costs of funds available to the financial intermediary, the

market tends to ration out borrowers to differing extents. In such

circumstances, borrowers are rationed out because they are considered

risky, but they may not be the ones that are the least important from a

social point of view.

These problems can be

aggravated because certain kinds of insurance markets for dealing with

risk are absent and because in some (especially, developing-country)

contexts, certain kinds of long-term contracts may not just exist. They

need to be created by the state, and till such time state-backed lending

would be needed to fill the gap.

Industrial development banks also help deal

with the fact that local industrialists may not have adequate capital to

invest in capacity of the requisite scale in more capital-intensive

industries characterised by significant economies of scale. They help

promote such ventures through their lending and investment practices and

often provide technical assistance to their clients. Some development

banks are expected to focus on the small scale industrial sector,

providing them with long-term finance and working capital at subsidised

interest rates and longer grace periods, as well as offering training and

technical assistance in areas like marketing.

Fundamentally of course, development banking is required because social

returns exceed private returns. This problem arises because private

lenders are concerned only with the return they receive. On the other

hand,

the total return to a project includes the

additional surplus (or profit) accruing to the entrepreneur. The projects

that offer the best return to the lender may not be those with the highest

total expected return. As a result, good projects get rationed out,

necessitating measures such as development banking or directed credit.

Finally, directed credit has positive

fiscal consequences. In contrast to subsidies, such credit reduces the

demand placed on the government's own revenues. This makes directed credit

an advantageous option in developing countries faced with chronic

budgetary difficulties that limit their ability to use budgetary subsidies

to achieve a certain allocation of investible resources.

It must be said that

development banks have played an important role in the Indian context. In

his deposition before the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance

(1999-2000) on 18 September 2000, the Managing Director of ICICI stated:

"disbursement by FIs constituted around fifty per cent of gross fixed

capital formation by the private corporate sector in the pre-liberalised

era. If you see the financial institutions' disbursement versus bank

credit to industry right from 1951 to the last year, we see that financial

institutions have provided significantly more credit for the creation of

capital in industry in India. It has grown year after year … Thus, the FIs

have played a pivotal role in the development of Indian industry and

have fulfilled their initial objective i.e. to spur industrialisation in

the country over the last three to four decades."

The corporatisation, transformation into universal banks and subsequent

privatisation of the DFIs is bound to undermine this role of theirs. The

justification for the conversion to universal banking as provided by the

Industrial Investment Bank of India (IIBI) in a written reply to the

Parliamentary Standing Committee indicates this: "Since

compartmentalisation of activities leads to greater transactions cost and

inefficiency, no financial intermediary can survive competition if it does

not allow itself flexibility to change. In the new financial environment, IIBI is of the opinion that a financial player may be either placed

naturally for resources like a commercial bank, or may be a pure financial

service provider and retailer like the NBFCs. Still another option is to

build a financial supermarket where all the services are available under

a single umbrella. The advantages are that they would be free to choose

the product mix of their operations and configure activities for optimum

allocation of their resources."

The CEO of ICICI made clear what this means in terms of emphasis: "When we

were set up, our role was to meet long term resource requirements of the

industry. With liberalisation, the role has slightly changed. It became

developing India's debt market, financing India's infrastructure

development, etc. With globalisation, I think, the role is set to change

further. Now we have to stress on profitability, shareholder value,

corporate governance, while at the same time not losing sight of our goals

– the goals that were originally set for us – and the goals that were set

up in the interim with liberalisation." Unfortunately, the emphasis on

those goals would remain only with regulation. But regulation is diluted

by liberalisation.

There is

another way in which the gradual dissolution of the core of India's

development banking infrastructure is related to the process of

liberalisation. This is through the effects of liberalisation on the

profitability of an institution like the IFCI, for example. According to

the

D. Basu Expert Committee, which was appointed by IFCI's governing board

immediately following its corporatisation and initial public offering in

1993, to examine the causes of the large NPAs accumulated by the

institution and suggest a restructuring, IFCI embarked upon a programme of

rapid expansion of business. To scale up the volume of business, it

increasingly raised resources from the debt markets. This was at a time

when interest rates were relatively high. In order to cover the high cost

borrowings, the institution was forced to make investments in what were

considered high yielding loan assets.

Unfortunately, this occurred

at a time when financial liberalisation had put an end to the traditional

consortium mode of lending, in which all major financial institutions

collaborated in lending to a single borrower as per a mutually agreed

pattern of sharing. Liberalisation was introducing an element of

competition among financial institutions. In the event, in search of high

returns IFCI chose to take relatively large exposures in several

greenfield projects (notably in the steel and oil sectors).

For a number of reasons, these projects did not deliver on their promise.

Many of these projects had expected to raise substantial equity from the

capital market as well as from the internal resources of group companies.

Depressed conditions in the capital market put paid to the first.

Recessionary conditions limited the second. Many of these groups were in

the traditional commodity sectors such as iron and steel, textiles,

synthetic fibres, cement, sugar, basic chemicals, synthetic resins,

plastics, etc. Besides the general recessionary environment, some of these

sectors were particularly affected by the abolition of import controls and

the gradual reduction of tariffs. Internal resource generation, therefore,

fell short of expectations. As a result, with inadequate own-financing in

the pipeline, many of these projects suffered from cost- and

time-overruns.

Unlike other financial institutions, IFCI had not diversified into other

types of businesses. Project finance still accounted for 94 per cent of

IFCI's business assets. As a result, the impact of NPAs arising from the

factors cited above was greater in the case of IFCI than in the case of

other institutions. In addition, there was sharp rise in IFCI's gross NPA

level in 1998-99 (Rs. 5,783.56 crore as against Rs. 4,159.84 crore in the

previous year), as a result of the implementation of the mandatory RBI

guidelines for classifying non-performing assets. As a result, certain

loans, particularly those relating to projects under implementation, which

had been treated as performing assets in earlier years, had to be

classified as non-performing.

The Basu Committee had noted that some of the factors referred to above

such as impact of trade policy liberalisation and tariff reduction,

recessionary conditions in the late 1990s, depressed conditions in the

capital market, etc., affected other DFIs and banks as well. However, the

impact was particularly pronounced in the case of IFCI, as the

concentration of risk relative to net worth was much higher. Also, as

already stated, other DFIs had started diversifying into non-project

related lending business. It was difficult to survive as a development

finance institution in the new environment.

Thus, the decline of development finance is clearly related to the process

of economic liberalisation. However, as a number of industry associations

have noted in recent times, it hardly is true that in a time of growing

competition for Indian firms from international business and a growing

liberalisation-induced shift in the investment and lending practices of

banks and NBFCs away from manufacturing, state support for domestic

private investment is not insignificant.

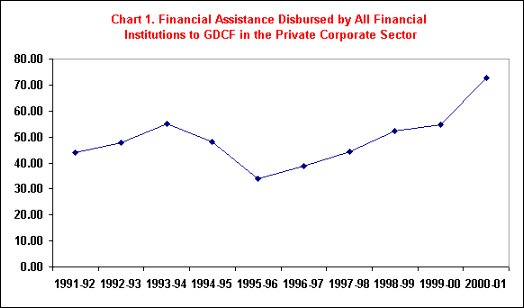

The view that development finance does not matter is countered by the fact

that thus far, right through the years of liberalisation, the state has

been forced to maintain a high ratio of disbursement of financial

institutions to Gross Domestic Capital Formation in the private corporate

sector (Chart 1). That ratio has risen sharply in recent times. However,

the argument that development finance is irrelevant is backed up by

evidence that in the case of many new projects, the share of equity

finance in total resources is quite high (Chart 2). The stock market is

replacing the DFIs, it is claimed. But such evidence is based on

information collected by the Department of Company Affairs from firms that

have issued prospectuses. That is, they are firms that have the ability to

and have chosen to tap capital markets and have hence issued prospectuses.

But, it is not clear whether these firms actually managed to raise the

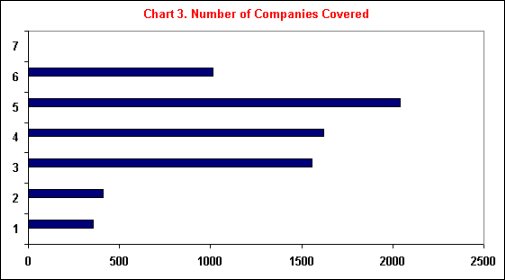

requisite capital from equity markets. And though the number of such

projects is growing, it still remains small (Chart 3). Further, the number

of such projects is quite volatile. Thus, relying on these figures to

justify undermining a framework that has served Indian industry well is

completely unwarranted. But, the reasons why these arguments are purveyed

is that they serve as the basis for justifying the government's decision

to adopt large-scale financial liberalisation in its bid to attract and

appease international financial capital. In that framework of policy,

support for building a domestic manufacturing base obviously does not make

sense.

© MACROSCAN

2004