Themes > Features

14.07.2011

The Latest Employment Trends from the NSSO*

No

sooner were the results of the 66th Round of the National Sample Survey

Organisation (relating to data collected in 2009-10) released, than

they became the subject of great controversy. Surprisingly, the controversy

was created not by critics of the government and its statistical system,

but from within government circles!

Some highly placed officials found that the results of this massively

large sample survey - conducted by one of the most respected governmental

statistical organisations in the developing world - contradicted their

own presumptions about the pattern of growth of the Indian economy.

Instead of therefore questioning their own priors, they decided that

the data must be wrong, and castigated the NSSO for its faulty investigative

methods (which they had earlier accepted without question). Others pointed

to specific problems with the data collection in the 66th Round, such

as excessive reliance on outsourced contract investigators, even though

this is not a very new problem, but rather has plagued the NSSO during

several of its recent rounds.

However amusing these official interventions may be, there is no doubt

that the results of the latest large survey of the NSSO reveal some

very important changes in the labour markets in India, and also in the

nature of the growth process that determines these changes. They therefore

deserve to be taken seriously and analysed in detail, including by the

same policy makers who otherwise currently choose to be in denial.

The starkest result relates to the slowdown in overall job creation,

which is what has generated the headlines about ''jobless growth''.

The NSS surveys are extremely inclusive in their definition of economic

activity, trying to capture all kinds of work including self-employed

work, part time work, home based work and so on, and therefore it is

wrong to think that they automatically exclude work that is outside

the formal sector. Even so they indicate a dramatic deceleration in

the rate of employment generation.

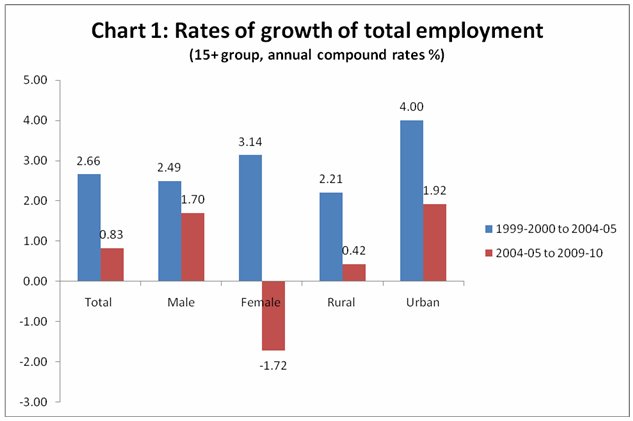

The charts below relate to usual principal status activity, which is

the main activity that people declare themselves to be engaged in on

a usual basis over the course of the previous year. They also refer

to those above the age of 15 years. The employment numbers have been

derived by applying the participation rates of the NSSO survey of 2009-10

to interpolated population figures from Censuses 2001 and 2011.

Chart 1 shows the dramatic deceleration in total employment growth,

from an annual rate of around 2.7 per cent in the previous five-year

period to only 0.8 per cent in the latest quinquennium. For females,

there was an absolute decline in employment - although it is certainly

true that this may reflect the lack of recognition of women's work,

since the biggest element of the decline relates to women's self-employment.

But even male employment shows quite a sharp deceleration. This slowdown

in employment generation is evident across both rural and urban areas,

though it was especially marked in rural India.

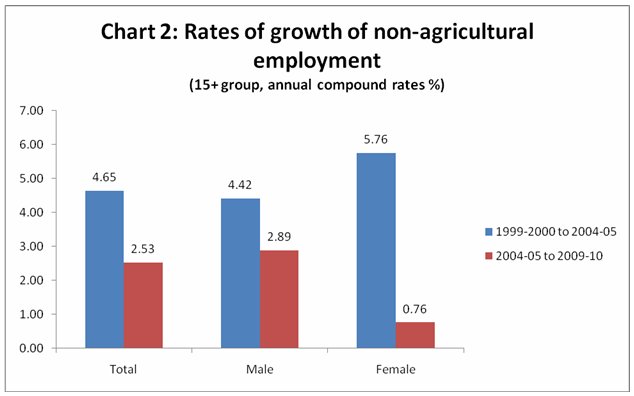

Nor should it assumed that the overall slowdown in employment generation

is simply the reslt of less employment in agriculture, which is after

all a typical feature of a broad process of industrialisation and development.

Rather, as Chart 2 indicates, rates of increase of non-agricultural

employment also fell sharply, indeed halved, for all workers taken together.

The collapse was sharpest for female workers. But even for male workers,

the slowdown in non-agricultural job creation was strongly evident.

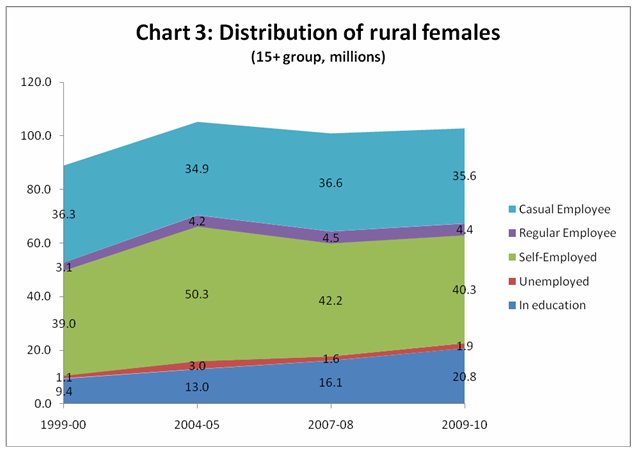

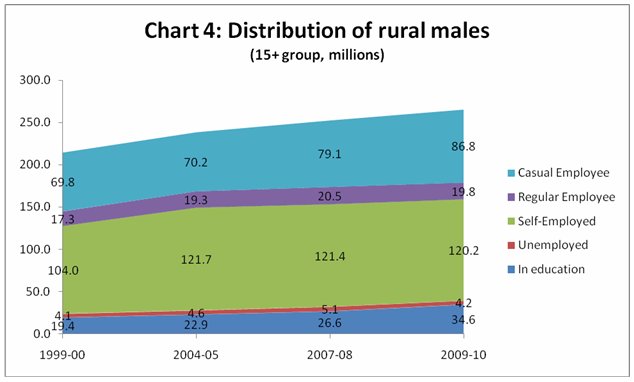

The

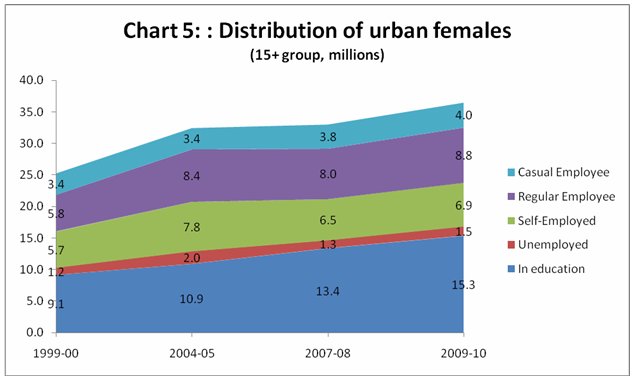

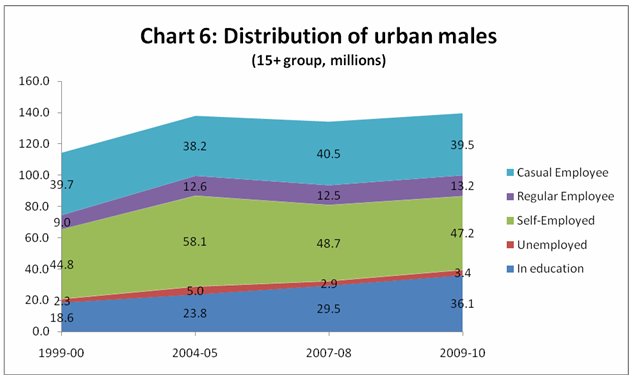

remaining charts provide evidence on absolute numbers of people, in

the 15+ age group, by gender and residence. These charts include data

from the smaller 64th Round of the NSSO, conducted in 2007-08, which

was specifically devoted to employment. This is useful because it allows

us to check whether the latest round is indeed a significant outlier,

or part of a trend that was already emerging a few years earlier.

From these charts, a more complex picture emerges, which clearly needs

to be analysed and understood carefully. It is evident that the latest

round really confirms the trends that were already beginning to show

by 2007-08, for most categories of workers. Therefore claiming that

this round specifically was affected by data collection problems is

not so convincing.

Charts 3 and 4 show the distribution of rural females and males respectively,

over the recent rounds, in terms of absolute numbers. For rural females,

it is certainly true that self-employment has collapsed, showing a decline

of more than 20 per cent compared to five years earlier. This is obviously

a matter that needs to be delved into, not in terms of the adequacy

of the investigative methods, but also in terms of questioning whether

the forms of self-employment that were said to have emerged were really

viable at all.

This question becomes significant because it is clear that self-employment

has also fallen for rural male workers. In both categories, the increase

has been in casual work. This increase is marginal for rural women (some

of whom are likely to have withdrawn from the work force) but quite

substantial for men in rural India. Regular employment has been largely

stagnant.

The good news is that there has been a substantial increase in those

engaged in education, for both rural females and rural males. The increase

is really quite significant, around 50 per cent over the five year period

for both males and females, and amounting to nearly 20 million more

young people (above the age of 15 years) being engaged in education

as the principal activity.

Could this be related to the evident decline in unemployment? Not really,

because it turns out that while unemployment seems to have fallen both

in terms of rates and absolute numbers, as is evident from the charts,

they have not fallen much for rural males though they have declined

slightly for rural females.

In

urban India, similar trends seem to be at work, as indicated in Chart

5 and 6. Self-employment has decreased for both men and women, and in

fact the decline is significantly more for urban men. Regular employment

has increased marginally for both categories. However, a note of caution

is necessary before such a finding gives rise to even minor celebration.

In the previous large survey round, the largest increase in regular

employment for urban women was in domestic service, as maid servants

and the like, which is not exactly the most desriable form of work.

So obviously, further investigation is necessary before we can adequately

intepret this trend.

Casual employment for both male and female workers has increased to

a greater extent. Specifically for the age cohort 25 to 59 years for

all India, there were around 18.2 million more casual workers, compared

to 6.4 million additional regular workers and 4 million more self-employed.

At the same time, unemployment rates appear to have fallen, especially

for this age group. The decline in unemployment even during a period

of very low aggregate job creation is a paradox that deserves further

examination.

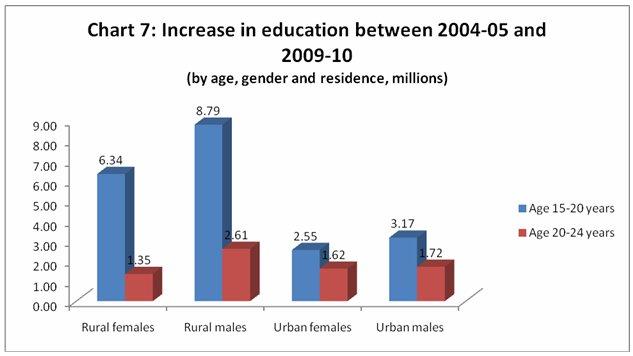

The increase in numbers of those engaged in education is so substantial

that it clearly requires another look. Chart 7 provides the absolute

numbers of increase of those engaged in education as the principal activity,

for the age cohorts of 15 to 19 years and 20 to 24 years. While the

biggest increases are for those presumably going in for secondary and

higher secondary schooling (in the age group 15 to 19 years) there are

also substantial increases in the older age group, suggesting involvement

in different forms of tertiary education.

This is good news, of course: the citizens of India deserve to be better

educated and the economy desperately needs a more skilled work force.

But it also points to a concern that should surely exercise our policy

makers, if they can bring themselves to look at a dataset that they

appear to reject at present. According to these data, there are nearly

30 million more young people putting themselves through more education

in the hope of being able to access better jobs. The total numbers of

such youth in secondary and tertiary education is at least 55 million.

Soon, perhaps even within the next five years, these young people will

enter the job market and expect to access employment that is at least

minimally commensurate with the efforts they have put in to receive

more education. But in the previous five year period, all forms of employment

(regular and casual paid work as well as self-employment) only increased

by around 28 million. If this sluggish pace of job creation continues,

there will be even larger gaps between aspiration and reality in India's

labour markets.

That such a combination is a recipe for enhanced social tensions and

political unrest is well known and has been reinforced by recent experience

across the world. If only for that reason, surely the government should

sit up to take notice of its own data?

*

This article was originally published in the Business Line, on July

12, 2011.

©

MACROSCAN 2011