Themes > Features

05.02.2004

The Right to Strike and Labour Repression in India

For some

time now, it has been evident that the stance of the Central government –

in terms of the executive authority and policy makers – has been anti-labour.

It is now apparent that the same tendency is also increasingly prevalent

among the judiciary, which has been delivering a series of judgements

which effectively operate to reduce the bargaining power and rights of

workers.

The recent Supreme Court judgement on the right of public employees to go

on strike, the arbitrary decision of a Kolkata High Court judge to ban

rallies on weekdays (which then was reversed); the Supreme Court's

reversal of its own previous judgement regarding the right to regular

employment of contract workers employed for prolonged periods – all these

are indications of a much broader and more dangerous socio-economic

process.

There is an underlying economic paradigm in all this, which essentially is

the neo-liberal market-oriented framework. This argues that labour market

"flexibility" is crucial for increasing investment and therefore

employment, and also for ensuring external competitiveness in a difficult

international environment. In this perception, legal protection afforded

to workers, in the form of curbs on employers' ability to hire and fire

workers at will, minimum wages or granting freedom to engage in collective

action such as the right to strike, all actually operate to reduce

employment.

In addition, in India there is a further argument, which is frequently

accepted even by well-meaning people with a concern for the poor. This

relates to the argument that the dualism in the labour market in India

means that there is a conflict between organised workers and those in the

unorganised sector.

It is often argued that the recognised trade unions ignore the problems of

the workers in the informal sector; that protection given to organised

workers actually allows or even militates against the improvement of

conditions of unorganised workers, who are anyway much worse off. This

perception then leads even some progressive people to accept that the

"privileges" extended to organised sector workers can be withdrawn, since

they are anyway so much better off than most other workers in the economy.

This argument is based on poor politics and even worse economics. The

politics is wrong because in fact any struggle over workers' rights

necessarily affects all workers, even if this is not immediately evident

to particular categories of workers. It is amply clear even from the

Indian experience, that every attack on organised workers has also reduced

the bargaining power of unorganised workers, that periods of repression of

organised labour have also been periods when informal sector workers find

themselves even more exploited.

The neo-liberal economic argument is that these rules which restrict

hiring and firing put undue pressure on larger employers and prevent

smaller firms from expanding even when the economics of their situation

otherwise warrants it. This creates a dualistic set-up in which the

organised or formal sector necessarily remains limited in terms of

aggregate employment and most workers, who remain in the unorganised

sector, are therefore denied the benefits of any protection at all.

The resulting dualism is characterised by an organised (or larger scale)

sector, which has relatively low employment, and an unorganised (or

smaller scale) sector, which has low investment. If aggregate economic

activity is to break out of this dualism and marry the advantages of both

sectors, the argument goes, it is necessary to get rid of the constraints

put on large employers in the matter of labour relations. The purpose of

various recent interventions - the recommendations of the Second National

Labour Commission, the recent Court judgement, the attempts to create more

"flexible" and less protective labour legislation – is to supposedly get

rid of these constraints on employers.

The belief is obviously that reducing such "rigidities" and curbing the

power of organised labour will increase private investment, increase

economic activity and improve productivity. All these in turn will improve

external competitiveness, which is considered to be so important these

days.

The chief problem with this argument is that it completely ignores the

major forces affecting investment, economic activity and therefore

employment. It is now accepted across the world that aggregate investment

does not respond to changes in the wage rate, but to broader macroeconomic

conditions such as the level of demand, the amount of public investment,

the expectation of external markets, and so on.

Labour costs are never viewed in isolation, but only in relation to labour

productivity, which in turn is affected not only by the level of

well-being, skill and education of the workers themselves, but also by

infrastructure conditions, the technology used in production, and so on.

In such a context, greater "flexibility" in labour markets might simply

mean the perpetuation of low wage-low productivity practices by employers,

rather than more economic growth.

While there is a formidable array of rights accepted by the Indian

Constitution for workers, and protective legislation as well, the problem

is that they are rarely achieved or enforced. Typically they can only be

even minimally enforced in the organised sector.

It is currently being argued by neo-liberal economists and others, that

these laws, which restrict employers' rights to dismiss workers at will

and stipulate some degree of permanency of employment, act as a major drag

on the profitability of the organised sector and on its ability to compete

with more flexible labour relations elsewhere. In this perception, a shift

towards a more universal contract-based system of labour relations, with

no assumptions of permanency of employment, is required to ensure economic

progress based on private enterprise within the current context.

But it can be argued in response to this, that labour laws are far less

significant as factors in affecting private investment, and therefore

employment, than more standard macroeconomic variables and profitability

indicators. Thus, the condition and cost of physical infrastructure, the

efficiency of workers as determined by social infrastructure, and the

policies which determine access to credit for fixed and working capital as

well as other forms of access to capital, all play more important roles in

determining overall investment and its allocation across sectors.

Expectations of demand and the extent of the market determine the volume

of investment.

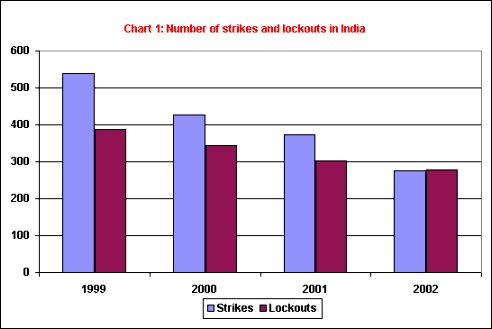

Indeed, it is also clear that in the recent past in India, strikes have

been far less relevant in disrupting production in the Indian economy,

than lockouts by employers. Chart 1 shows the actual number of strikes and

lockouts in India over the period 1999-2002. While both have been coming

down over this period, the decrease in the number of strikes has been more

dramatic, and in 2002, the number of lockouts was actually higher.

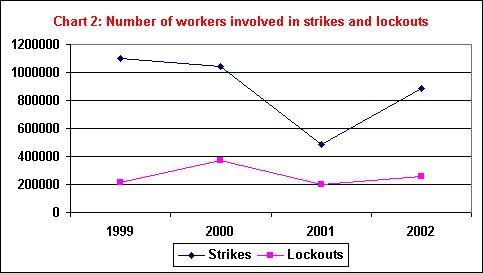

Chart 2 provides information on the number of workers involved in strikes

and lockouts - here, the evidence is that strikes have involved a greater

number of workers than lockouts. However, obviously strikes have been of

shorter duration and therefore less disruptive of production and economic

activity, as shown by the actual working days lost, in Chart 3. The

persondays lost to lockouts has been consistently higher than the loss due

to strikes, and was nearly double in 2002.

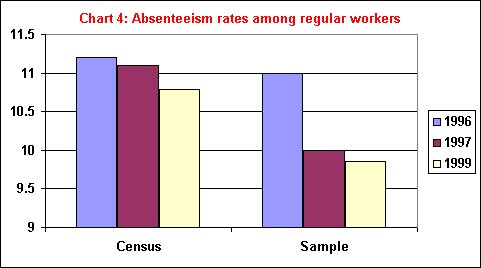

It is also likely that workers' discipline has improved in general, as

absenteeism rates among regular workers seem to have come down quite

drastically in the recent past, as indicated in Chart 4. Similarly, labour

costs per personday worked (Chart 5) have been broadly flat, despite large

increases in labour productivity, so that obviously workers have not

garnered any advantage from technological progress, the gain from which

have accrued to employers instead.

It is in this context that the right to strike must be considered in

India. Obviously, strikes are ultimate weapons, which are only resorted to

by workers when all other means of struggle and negotiation have been

exhausted. In recent Indian experience, the working class as whole has

been relatively responsible and only used strikes in extreme cases when

negotiations have failed completely or when employers have appeared to be

completely insensitive to genuine demands of labour.

Denial of this right would lead to a massive deterioration of the

bargaining power of workers, which has already been weakened by various

macroeconomic processes such a global integration and the withdrawal of

the state from important areas of regulation and provision. In any

society, the socio-economic rights of all citizens, including workers,

have never really been freely gifted by the state or employers; their

recognition and implementation have always been the result of prolonged

struggle on the part of workers and other groups.

Changing the conditions of such struggle amounts to changing the

possibility of ensuring these basic rights, which are even recognised in

the Constitution of India. Therefore, the right to strike for workers

remains an important instrument for ensuring the basic economic rights of

all citizens.

© MACROSCAN

2004