Themes > Features

08.04.2011

Whither Industrial Growth?

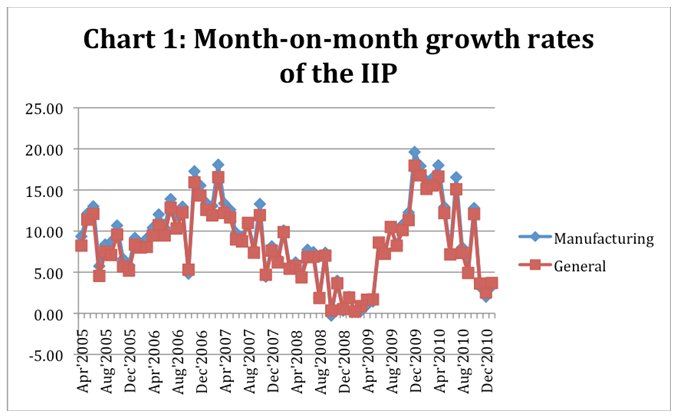

When GDP growth bounced back to close to 9 per cent after the slump induced by the global recession, India’s growth performance once again appeared remarkable by global comparison. But one feature that has sullied this record is evidence of a deceleration in industrial growth in recent months. Month-on-month annul growth rates which stood at between 10 and 18 per cent during most months of the August 2009 to July 2010 period, have since decelerated and stood at less than 5 per cent in four of the five most recent months (September 2010 to Jan 2011) for which data are available (Chart 1). As a result, even though annual rates of growth are still respectable (Chart 2), some disquiet has been expressed in various circles.

It

is useful to view the recent downturn as being part of longer-term trends

in industrial growth. Unfortunately, since IIP figures have been recompiled

from April 2004 onwards, using the new series of WPI to deflate IIP

items for which production is reported in value terms, fully comparable

month-on-month rates of growth are available only from April 2005. But

examining this series (Chart 2) points in two directions. The first

is that the recent downturn is sharper than the one experienced during

the immediately preceding cycle. Second, while the previous downturn

may have begun earlier, it stretched across the period that saw the

onset of the global financial crisis and witnessed the global recession.

On the other hand, the more recent downturn has occurred in a period

when the recession had bottomed out and the world economy was experiencing

a recovery.

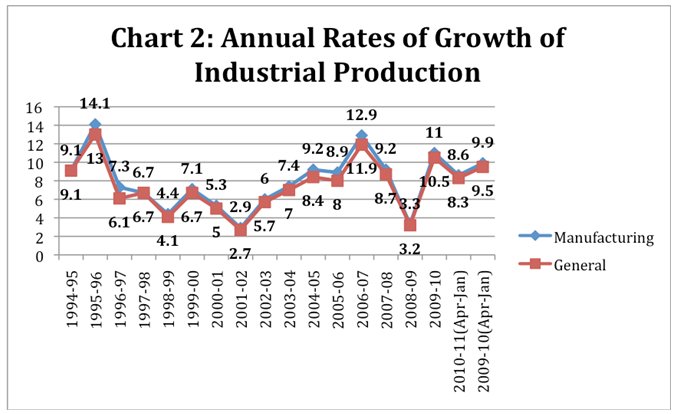

One inference that could be drawn from this is that it is not so much

an export recovery as developments in the domestic market that underlie

the deceleration in industrial growth. This is of significance because,

as Chart 2 illustrates, if we take a long view, after a mini-boom during

the mid-1990s, industrial growth remained low for most years during

the 1996-97 to 2002-03 period. After that, growth recovered and reached

a peak in 2006-07. And, if we exclude 2008-09, which was a year of slow

growth induced by the global recession, it appears that Indian industry

had subsequently settled into a trajectory of growth of around 8 to

9 per cent a year. What the recent slowdown does is question the sustainability

of that manufacturing growth trajectory.

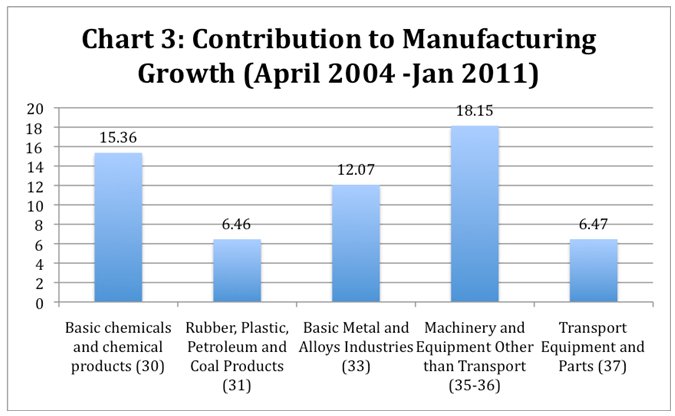

The sustainability issue is all the more relevant because of the concentration

of post-2004 growth in a few industrial sectors. Consider for example

an analysis in which the contribution of each of 17 two-digit industry

groups to aggregate manufacturing growth during April 2004 and January

2011 is computed. This is done by multiplying by the trend rate of growth

of the relevant group with its weight in the index of manufacturing

production. The resulting figure shows that that there are only five

of these seventeen that contributed at least 5 per cent of the observed

growth in manufacturing over this period. These five were all metal-

or chemical-based and included: (i) Manufacture of Basic Chemicals and

Chemical Products (except products of petroleum and coal) (Group 30

of National Industrial Classification 1987); (ii) Manufacture of Rubber,

Plastic, Petroleum and Coal Products (Group 31); (iii) Basic Metal and

Alloys Industries (Group 33); (iv) Manufacture of Machinery and Equipment

Other than Transport Equipment (Group 35-36); and (v) Manufacture of

Transport Equipment and Parts (Group 37). These five out of 17 industry

groups accounted for as much as 58.5 per cent of the total growth in

the index of manufacturing production (Chart 3).

This concentration of growth in the metal- and chemical-based industries

has a number of possible implications. The most obvious of these stems

from the fact that the metal- and chemical-based industries tend to

be among the more capital intensive in the industrial sector. Employment

per unit of investment or output in these industries is much smaller

than in many other manufacturing sectors. Hence, if growth is biased

in favour of the metal- and chemical-based industries, the responsiveness

of employment in the manufacturing sector to a unit increase in manufacturing

output would be lower than would otherwise be the case. Growth could

be jobless or inadequately job creating. This has indeed been a feature

characterising registered manufacturing growth in India in recent years.

But there could be implications for the nature of growth itself. To

start with, inasmuch as it is domestic demand that drives growth in

these industries, that demand would in all probability be fuelled by

(i) public expenditure, particularly public investment, which tends

to be biased in favour of demand for these industrial products; (ii)

upper income group consumption of such commodities that are normally

not ''necessities''; and (iii) debt-financed household investment (in

housing), purchases of automobiles and consumption of ''luxuries''.

These are the kinds of demands for final products that tend to be directed

at the metal- and chemical-based industries. Hence, growth based on

such industries would depend on the availability of one or more of these

sources of demand as stimuli for the industrial sector.

Besides being driven by demands of these kinds, these industries are

normally in the nature of clusters, in the sense that the metal- and

chemical-based industries are dependent on inputs from similar industries

and serve, if at all, as inputs for downstream metal- and chemical-based

industries. This results in the fact that growth or deceleration in

these sectors tends to be ''cumulative''. If exogenous demand trends

induce a slowdown of growth in some of these industries, they have a

dampening effect on the growth of related industries as well.

These two features of growth, in turn, have implications for the sustainability

of the growth process. If growth is to continue, one or more of these

sources of demand must remain strong. There are limits to the degree

to which upper income demand can continue to sustain growth, since even

though incomes are high in this group, the share of the population included

is extremely small. Hence, public expenditure and debt-financed investment

and consumption have to be sustained.

A feature of fiscal reform policy has been an attempt by the government

to rein in deficit spending by reining in expenditures. This tendency

has been stronger because tax policy reform in recent years has focused

on the reduction of customs duties as part of trade liberalisation,

on a reduction of direct taxes to incentivise private saving and investment,

and of indirect taxes as part of a process aimed at rationalising them.

As a net result the tax-GDP ratio has been significantly lower than

would have been the case if these changes had not been made. A corollary

is that for any given reduction of the fiscal deficit, the expenditure-reduction

required tends to be higher than would have been the case earlier. Thus,

the more successful is fiscal reform in terms of tax and deficit reduction,

the larger would be the relative reduction in public expenditure.

From the point of view of industrial growth, therefore, the successful

implementation of fiscal reform implies a transition to a deflationary

fiscal environment with dampened demand. It is possible that it is this

effect that explains the slowdown in industrial growth in the period

between the mid-1990s and 2003-04 (Chart 2). But that does raise the

question as to the factors underlying the subsequent recovery in industrial

growth. That recovery cannot be attributed to a reversal of fiscal reform,

except for the period after the onset of the downturn induced by the

global recession in 2008, when the government responded with a fiscal

stimulus that was adopted also because of the parliamentary elections

scheduled for April-May 2009.

Thus, during much of the period of high growth after 2003-04, the stimulus

to industrial growth in all probability came from debt-financed private

investment in housing, private purchases of automobiles and private

consumption. Growth based on debt-financed demand, however, requires

the continuous expansion of the universe of the indebted. While enhanced

availability of cheap liquidity and financial innovation that can bundle

and distribute risk can encourage such expansion, at some point the

threat of unsustainable defaults would slow, if not stop, the process.

That would slow demand growth as well. This is perhaps what explains

the evidence of the decline of the month-on-month growth rates of the

indices of manufacturing and industrial production after March 2007,

which was before the global recession and well before its effects were

felt in India.

Once the effects of the recession were felt, industrial growth slumped.

It was the response of a government, with an eye to the impending elections,

to that slump, that led to the recovery and return to high growth. But

the fiscal stimulus encouraged by the election was a once-for-all effort

on the part of a government that was committed to fiscal conservatism.

When it returned to power it chose to unwind the stimulus. It is because

that unwinding process was not accompanied by any neutralising surge

in debt-financed private investment and consumption that we have witnessed

over the last fiscal a significant deceleration in month-on-month growth

rates in industrial production, which now appears to be quite steep.

It is indeed too early to conclude with confidence that this is what

is happening. But that seems to be an argument that explains trends

in industrial growth over the medium term. If so, we can expect that

we are set for a return to a period of slower industrial growth as happened

in the second half of the 1990s. Unless once again, some other stimulus,

such as exports, provides the basis for growth.

©

MACROSCAN 2011