Themes > Current Issues

6.12.2005

The Employment-Poverty Link in Bangladesh

Jayati Ghosh

For

nearly three decades now, the economy of Bangladesh has been growing

at slightly more than 4 per cent, and per capita income growth even

accelerated in the 1990s compared to the previous decades. In the 1980s,

per capita GDP had grown slowly at the rate of about 1.6 per cent per

annum. In the first half of the 1990s, the growth rate accelerated to

2.4 per cent and further to 3.6 per cent in the second half of the decade.

Of

course this increase in the per capita growth was mainly because of

the demographic transition involving declines in rates of population

growth (from 2.1 per cent in 1990 to only 1.6 per cent in 2000), since

there was no apparent break in the trend rate of growth of around 4

per cent over the entire period. However, there was clearly greater

macroeconomic stability in terms of reduced rates of inflation (from

an average of 9.9. per cent per annum in the early 1980s to an average

of 5.6 per cent per annum by the end of the 1990s).

However, it is notable that this aggregate economic expansion has had

less apparent direct impact on poverty reduction. It is certainly the

case that the long-term trends in poverty show notable progress since

Independence, from 71 per cent in 1973-74 to around 45 per cent in 2000.

Chart

1 provides estimates of poverty according to two different methods:

in terms of a poverty line derived from the cost of basic needs, and

in terms of direct calorie intake. While some reduction in the incidence

of poverty is evident, this is actually less rapid than occurred during

the 1980s. Clearly, the reduction in poverty has not been commensurate

with the expectations generated by the macroeconomic pattern of relatively

stable and non-inflationary growth.

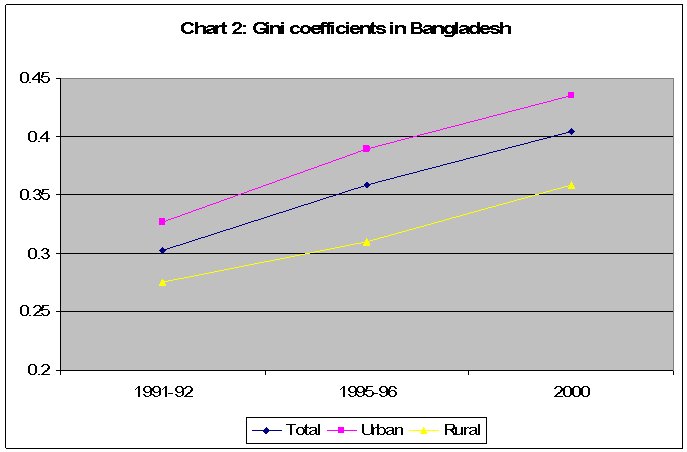

Some of the reason for this is probably the substantial increase in

inequality over this period, as evident from Chart 2. The main source

of increasing inequality was the increasingly unequal distribution of

both non-farm income and remittance income.

The

outward-looking macroeconomic policy pursued by Bangladesh in the recent

past did succeed in stimulating some parts of the economy, especially

readymade garments and fisheries which were the most rapidly growing

activities in the 1990s. But these activities still have a relatively

low weight in the economy, and most (at least two-thirds) of the incremental

growth in the 1990s originated from the non-tradable sectors - mainly,

services, construction and small-scale industry. The demand stimulus

for this came from three major sources - the increase in crop production

in the late 1980s, accelerated flow of workers' remittance from abroad

and incomes generated by the readymade garments industry.

However, these sectoral contributions of changing GDP were not exactly

matched by changes in employment patterns. Chart 3 show the extent of

growth of labour force in different sectors over the two halves of the

decade of the 1990s. The most rapid growth has been in financial services,

but these still constitute a very small part of total employment. Manufacturing

employment has grown only marginally, after falling in the previous

decade. While the new export sector of ready made garments has provided

an important source of new employment (especially for women) total employment

in aggregate manufacturing has actually declined, in both relative and

absolute terms. There has been significant de-industrialisation, particularly

in the traditional sectors, which have suffered from import penetration.

However, agriculture has shown substantial increase in employment generation

to around 4 per cent per annum in the second half of the decade, reflecting

the impact of various policy measure offering more incentives to cultivators

from the mid-1980s onwards. While construction increased its share of

GDP rapidly, the rate of employment generation decelerated in this sector.

Other services sectors also showed decelerating employment growth in

the second half of the 1990s.

In

the early 1990s there was a marked improvement in the government's budgetary

position along with an equally marked increase in the domestic saving

rate. However, the increase in the saving rate was not matched by a

commensurate response from private investment, at least in the early

1990s. However, in the second half of the 1990s, while public investment

rates remained broadly the same, private investment increased causing

the aggregate rate to increase to more than 21 per cent.

The sectoral allocation pattern of development spending has undergone

some significant changes in the last two decades, reflecting the changing

role of the government under the economic reforms. Allocations have

fallen appreciably for a number of directly productive sectors - most

notably, manufacturing industry, water resources, and energy, and agriculture,

and increased for transport and communication, rural development, education

and health.

Open unemployment rose risen from 1.8 per cent of the labour force to

as much as 4.9 per cent, and was as high for women as for men, while

underemployment in 2000 was estimated to be very high at around 31 per

cent. What is also of concern is the dramatic increase in the ratio

of self-employed to total workers, as indicated in Chart 4. In general

the shift to self-employment in non-agriculture tends to be less rewarding

in income terms for the poor, than the shift to regular work. However,

there has been only a very slight, almost negligible increase in the

share of regular employment.

So it is apparent that one crucial link to ensure more rapid poverty

reduction - the generation of productive employment - has simply not

been operating in a way that would show more effective results. rather,

employment elasticities of output growth have been low or falling in

most sectors, and the persistence of large-scale underemployment implies

the continued proliferation of low productivity jobs, most typically

now in the services sector.

There

is a common perception that the high presence of micro-credit delivery

systems in Bangladesh has operated to provide a cushion for poor households

in case of shocks such as crop failures, floods and other natural disasters,

etc. It has also helped to improve the relative position of women. However,

the basic features of micro-credit (short-term, relatively small amounts,

groups lending pressure for prompt repayment) mean that it has not contributed

much to asset creation among the poor, or to sustained employment generation.

In fact, the poverty reduction that has occurred may be related more

to other forms of public expenditure. The expansion of public transport

infrastructure, especially roads networks in the 1980s, may have contributed

to subsequent rural development which in turn assisted some of the reduction

of poverty in that later period.

However, trade liberalisation had the counter effect of reducing the

viability of many small producers, so the net effect of all the policy

changes over the period is not clear. It is likely that some of the

effects of openness were positive (as in the garments industry) others

were adverse for livelihood and therefore poverty, and these were to

some extent mitigated by the spread of public transport networks and

the availability of micro-credit.

© MACROSCAN 2005