Themes > Features

2.11..2010

Is Food Inflation finally coming down?

The

past three years have witnessed a period of very rapid and sustained

increase in food prices, which has very significantly affected the living

standards of the bulk of the Indian population. Food price inflation

has been in double digits for an extended period, and all the declared

policies of the government have done little to reduce it. Indeed, some

policies such as the deregulation of petrol prices may well have further

contributed to such inflation.

For

almost a year now, some important policy makers and spokespersons of

the government have been promising that food inflation will come down

to 6 per cent within a few months. This claim has been made periodically

since last October; yet, food prices have continued to rise at very

rapid and even increasing rates.

This has also led to a change in the official policy thrust, towards

inflation control through monetary policy notwithstanding the negative

effect this may have on output and employment. Thus the Reserve Bank

of India is so concerned about the continuing high rates of food inflation

(which it interprets as reflecting excess demand) that it is increasingly

veering towards putting up interest rates in order to restrict price

increases. But there are several reasons why this is not likely to be

the appropriate strategy.

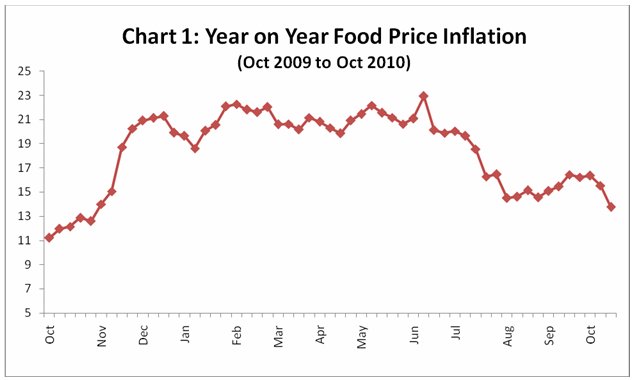

Chart 1 shows the year-on-year rate of food price inflation over the

past year by week. The rapid increase in the food inflation rate to

20 per cent and more from November 2009 reflected the impact of the

poor kharif harvest consequent upon the bad monsoon. This was coupled

with the effect of adverse expectations. The food inflation rate remained

persistently high for nine months thereafter. It is worth noting that

there was no deceleration even after the rabi harvest, which (while

not particularly good) was certainly not as bad as the previous kharif.

It is only in the past three months that there has been some deceleration

in the year-on-year food inflation rate, although it still remains very

high at around 15 per cent in annual terms.

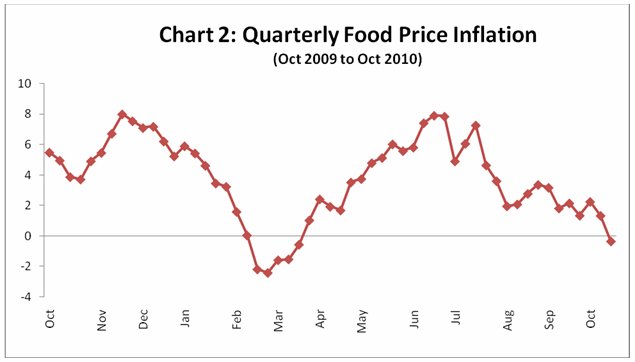

Another way of tracking the seasonal movement of food prices is to look at the quarterly rate, that is, the rate of increase in food prices relative to the previous quarter (13 weeks previously). Chart 2 provides this information, and suggests that there was some effect (although muted) of the incoming rabi harvest on overall food prices, which actually fell in March and part of April. It is also evident from Chart 2 that the most recent kharif season has been associated with a deceleration in inflation (though not yet an absolute decline in prices) as the effects of a munificent monsoon in large parts of peninsular India are felt. This is notwithstanding the relatively poor rainfall that has affected much of the Eastern region.

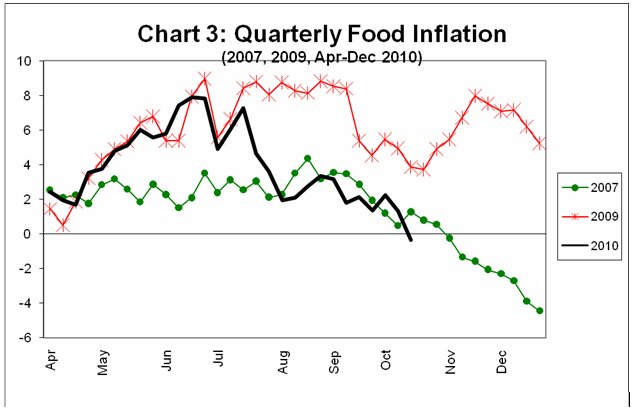

Looking

at the quarterly pattern allows us to compare the current year with

two recent years that have been associated with very different patterns

of price movement: 2007 (which was a very good year in terms of agricultural

output in both kharif and rabi seasons) and 2009 (which turned out to

be a very poor year for kharif and only a moderate year for rabi). In

2007, quarterly food inflation rates were moderate but positive until

October, and then even turned negative from October, indicating absolute

price declines (which are quite normal in periods of good harvests).

In 2009, by contrast, quarterly food inflation rates rose quite sharply

between May and July, and then stayed very high until October. The slight

deceleration in October and November was not sufficient to ensure any

real decline in the year-on-year inflation rate, as was observed in

Chart 1. And, of course, the poor kharif harvest in that year meant

that the quarterly inflation rate then rose sharply in the last two

months of 2009, ensuring the very high annual rates in excess of 20

per cent that were observed from then onwards.

What is particularly interesting about Chart 3 is the food price behaviour that is indicated for the current fiscal year. For the first four months of fiscal 2010-11, the quarterly food inflation rates have looked very similar to those that prevailed in 2009, which as we have seen was a bad year in terms of agricultural output. However, since late August the pattern appears to have changed, and the pattern of price movements much more closely tracks the price behaviour of 2007, which was a good harvest year. Since all indications are that the current year will witness a good kharif harvest, there is sufficient reason to expect that the quarterly inflation rate may turn negative post-harvest, as had occurred in 2007 for example.

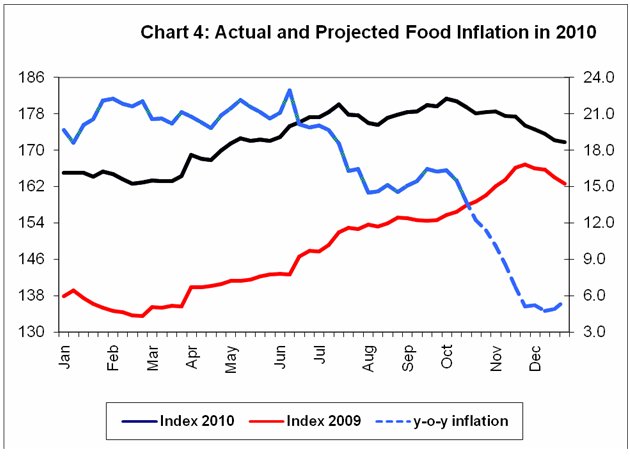

If

this does actually transpire, then it may well be that the rate of food

price inflation will decline in the near future. Chart 4 projects the

price behaviour noted from Chart 3 onto the coming months of this year,

in terms of the possible implications for the year-on-year food inflation

rate. If the seasonal price pattern tracks the movements in 2007, which

may be expected because of the good kharif harvest, there is likely

to be a decline in the year-on-year food inflation rate to just below

6 per cent in the coming months.

This in turn means that heavy-handed monetary policy measures designed

to curb such inflation, especially those affecting the base interest

rate, are likely to be excessive and even unnecessary given the likely

movement of food prices.

However, this does not mean that there is any justification for complacency

on the food price issue, nor does it suggest that the question of food

security for the population is any less pressing. Note that much of

the decline in food inflation rates that may appear shortly is because

of the base effect of very high food prices in the previous year. Also,

money wages of most workers (both wage workers and self-employed) have

certainly not kept pace with the food price increases.

A further factor must be borne in mind. India continues to be affected

by global prices of important food items, and there are clear indications

of another price upsurge in food markets in global trade. For example,

wheat prices in the Chicago market (which is the typical benchmark for

the global trade price) have increased by more than 70 per cent in the

three months up to late September. There is once more evidence of speculative

activity in the commodity futures markets, driven by index traders.

What makes the problem more pressing for India is that the Indian government

has once again allowed futures contracts in wheat from May 2009, having

lifted the ban specifically for this commodity. If the global speculative

pressures affect India, including through the impact on the local futures

market, this may provide a source of food price inflation that is unrelated

to local supply factors. In such a case, any bets on future food price

movements would be off.

©

MACROSCAN 2010