| |

|

|

|

|

The

Left and Elections in West Bengal* |

| |

| May

18th 2011, C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh |

|

This

is clearly an important moment in Indian politics.

The dust has still not settled in the five states

where elections to the state assemblies were held,

but their impact is already reverberating across the

country. Not just the elections in the states of West

Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Assam, Kerala and Puducherry,

but even by-election results (as in Kadapa in Andhra

Pradesh) may turn out to have national significance

for the course of both politics and economic policies

at central and state levels.

The two states where Left Front governments were in

power have captured the bulk of media attention. And

within that, the focus has been on West Bengal, not

only because of the importance of Left politics in

that state for the Left movement in the country as

a whole, but because the Left Front government there

had managed to win elections for a record seven consecutive

elections. In Kerala, where incumbent governments

have been ejected by voters every five years for nearly

four decades, the vote was extremely close and the

incumbent Left Democratic Front very nearly made it

back to power. Indeed the victory of the opposition

may well be seen as Pyrrhic because of the likely

instability of the future UDF coalition government.

Across the board, it is the Left's loss of state power

in West Bengal which is being widely seen as the most

devastating and full of portent for the future. Interestingly,

this view seems to be shared by both opponents and

proponents of organized left parties in the country:

that this huge loss shows that the people have decisively

rejected the Left Front government, and that the major

left parties in the country (such as the CPIM and

the CPI) will find it impossible to recover from this

massive defeat. In some quarters this is being celebrated;

within the Left, there is a sense of desolation and

anxiety; in other quarters, more dispassionate observers

are concerned about the lack of the moderating power

of the Left in preventing a national rightward lurch

particularly in economic policies.

Mainstream media responses have contributed to this

by talking about ''the death of the Left'' and similar

stereotypical responses. But how much of this is actually

justified by the voting patterns that have been revealed

in the latest elections? There is no question that

the Left Front government has been handed a resounding

defeat, with most Ministers losing their seats and

the seat share of the parties involved in the coalition

falling to one-third of the former strength in the

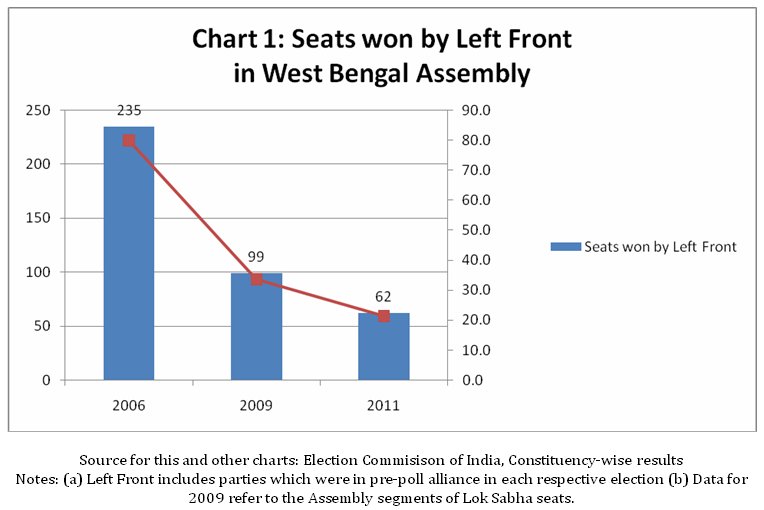

Assembly. Chart 1 shows the number of Assembly seats

held or implicitly garnered by the Left Front in successive

elections since its historic seventh victory in 2006.

It is clear that there has been a very significant,

even dramatic, decline.

Chart

1 >> Click

to Enlarge

But

note that the number of seats gained in 2006 represented

an extraordinary achievement: 80 per cent of Assembly

seats (well over the two-thirds majority) claimed by

a government that had already been in power in the state

for three decades. This is an achievement unparalleled

in independent India, and probably anywhere in the world.

It is rare to find a democratically elected government

that retains power for a second or third term. When

this happens anywhere else in India, the mainstream

media are quick to declare it as a victory for good

governance, though they have always been much more grudging

of Left victories. That the Left Front government in

2006 was able to retain power to garner a record seventh

term and even add to its tally of Assembly seats compared

to 2001 indicates that it had an appeal among the electorate

that was both unprecedented and remarkable.

Some would argue that the sharp decline in the number

of seats thereafter suggests that the government then

squandered this advantage. Certainly the causes for

the decline can and will be analysed threadbare inside

and outside the various parties that formed the Left

Front government. Many factors must have played roles,

of which the poor handling of the policy of land acquisition

for industrialisation is the one that is most commonly

cited. The proactive coming together of all sorts of

disparate and otherwise conflicting political elements

at both centre and State level, with the sole aim of

dislodging the Left from its bastion, was also definitely

important.

But the combination of complacency and exhaustion that

can be created by 34 years of uninterrupted rule should

not be underplayed either. This combination was evident

to many external observers. Of course it was then rudely

shocked by the experience of the 2009 general elections.

But it may be that the subsequent attempts at political

revival among Left supporters were too belated and inadequate

to cope with what is only a very natural human desire

among the people for political change, even if the nature

of that change is unpredictable or problematic.

But does this mean that the people of the state have

decisively rejected the politics of the Left? A detailed

look at voting shares provides a more nuanced understanding.

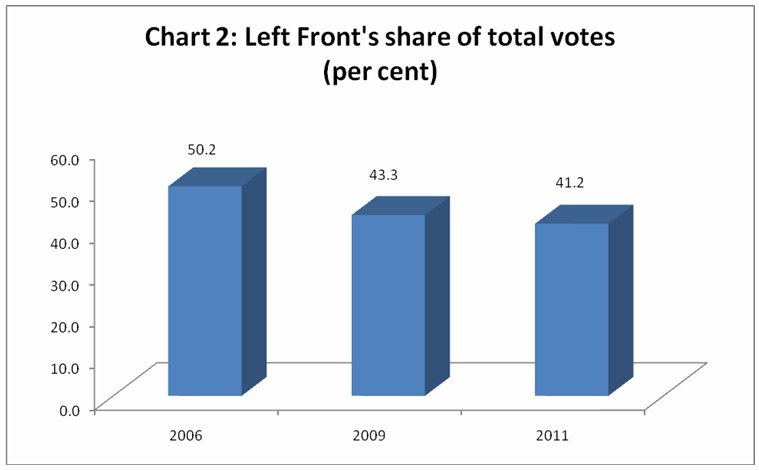

Chart 2 indicates that even in this latest Assembly

election, when the verdict of the electorate appears

to be so decisive against the incumbent government,

the Left parties still managed to garner more than 41

per cent of the votes. This is still no mean achievement

for a government that has been in power for nearly 35

years.

To put this into perspective, it should be noted that

most state governments in India are holding on to power

on the basis of much smaller vote shares, generally

well below 40 per cent. This includes the Congress government

in Andhra Pradesh (whose position appears much more

tenuous after the Kadapa by-election) and the Congress-NCP

coalition government in Maharashtra. This also includes

the Nitish Kumar government in Bihar, which is the mainstream

media's current favourite and is being portrayed as

a model for Mamata Bannerji to follow. It is only because

politics in West Bengal (as in Kerala) is much more

polarised between two contending groups that the first

past the post system does not generate parties that

can come to power with relatively small shares of the

vote.

Chart

2 >> Click

to Enlarge

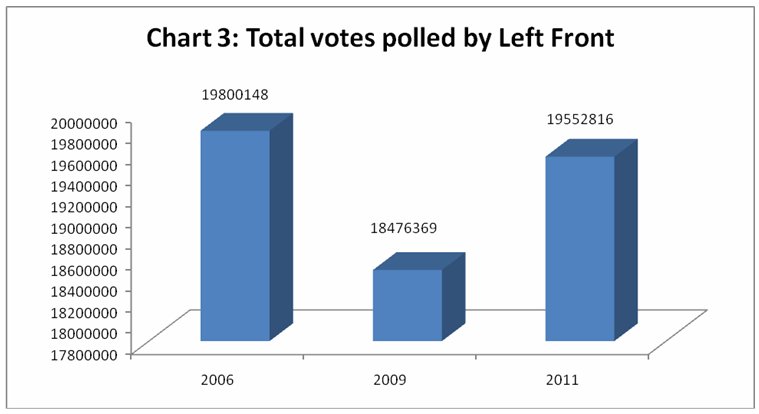

It may be more surprising that in terms of the actual

number of votes polled, the Left Front has significantly

improved upon its performance in the 2009 general elections,

and has even come close to the number of votes it managed

to get in its record-breaking seventh victory in 2006.

Chart 3 shows that in this Assembly election, the Left

Front managed to attract nearly 1.1 million additional

voters compared to 2009. Not only was the Left Front

vote in 2011 very close to that in 2006, this increase

was almost equal to the extent by which the Left Front

had fallen short of the votes of the TMC-Congress combine

in 2009.

This helps to explain the optimism that was evident

among Left party cadres just before the results were

declared. This may partly reflect the disconnect between

the parties and the people, as a result of which they

did not anticipate the electoral debacle. It can also

be partly understood when it is recognised that in fact

many more people actually did come out to vote for Left

parties than had done so in 2009.

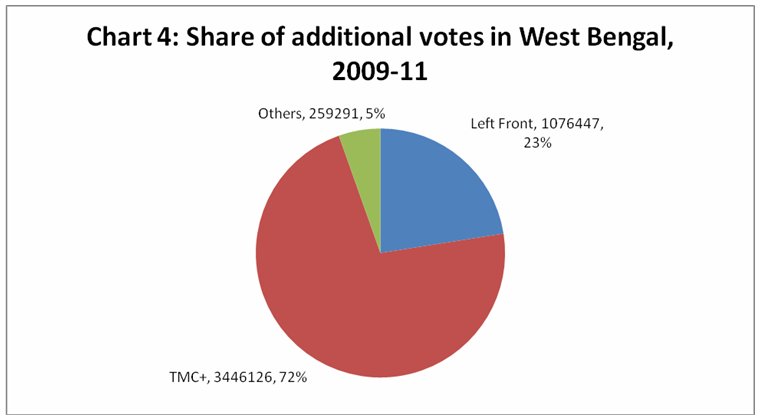

The disconnect partly comes from the fact that the party

cadre apparently did not anticipate that many more people

would turn out to vote for the opposition. Overall there

was a significant increase in the number of votes cast

overall between 2009 and 2011, of nearly 4.8 million

votes according to the Election Commission's preliminary

estimates. This was in part because of a 3.7 million

increase in size of the electorate, i.e. new young voters,

and in part because voter turnout increased sharply.

The difference in this election is really that the opposition

combine of Trinamool and Congress parties managed to

swing a much larger share of these new voters to vote

for change in government.

Chart

3 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart

4 >> Click

to Enlarge

Chart 4 shows that of the additional votes cast, the

Left Front managed to get less than a quarter, and that

nearly three-quarters accrued to the Opposition combine.

It is also worth noting that more than half the new

voters were women. Firstly, the number of women on electoral

rolls increased somewhat more than men; and secondly,

more of them voted than before. While the male voting

percentage increased from 82.3 per cent to 84.4 per

cent, the female turnout went up from 80.3 per cent

to 84.5 per cent, exceeding male turnout in a state

where traditionally voter turnout amongst women voters

has been much less than among men. This is obviously

a major aspect that the Left needs to introspect on.

Whatever one may think of the result, there can be no

denying that this shows that Indian electoral democracy

is among the most vibrant in the world.

Obviously none of this changes the basic reality of

this particular state assembly election - that it has

involved a major defeat for the Left that may have far-reaching

implications. But it can by no means be taken as showing

that there is massive dimunition in Left support among

the people of West Bengal. Certainly it is not just

premature but downright wrong to write off the Left

as a major political force. This result too is likely

to have a significant bearing on how politics evolves

in the state in future.

*

This article was originally published in The Businessline,

17 May, 2011.

|

| |

|

Print

this Page |

|

|

|

|