Themes > Features

21.03.2005

The Unfulfilled Potential of the ICDS

This

year marks the 30th anniversary of the Integrated Child Development

Scheme, or ICDS, which was initiated in October 1975 in response

to the evident problems of persistent hunger and malnutrition especially

among children.

Since

then, the ICDS has grown to become the world’s largest early child

development programme. The coverage of the Scheme has expanded rapidly,

especially in recent years. From an initial 33 blocks in 1975, the

programme covered an estimated 6,500 blocks by 2004. There are almost

600,000 anganwadi workers and an almost equal number of anganwadi

helpers providing services to beneficiaries throughout the country.

According to the government, the programme currently reaches 33.2

million children and 6.2 million pregnant and lactating women.

Officially, the objectives of the Scheme are:

-

to improve the nutritional and health status of children in the age group 0-6 years

-

to lay the foundation for proper psychological, physical and social development of the child

-

to reduce the incidence of mortality, morbidity, malnutrition and school drop out

-

to achieve effective coordinated policy and its implementation amongst the various departments to promote child development

-

to enhance the capability of the mother to look after the normal health and nutritional needs of the child through proper nutrition and health education

Accordingly,

the ICDS involves the setting up of anganwadi centres, each of which

is intended to cater to a population of around 1,000 in rural and

urban areas and to around 700 in tribal areas. The anganwadi worker

and helper, who are the basic functionaries of the ICDS, run the

anganwadi centre and implement the Scheme in coordination with the

functionaries of the health, education, rural development and other

departments. They are called ‘social workers’ and are paid an honorarium

of Rs. 1,000 per month for the worker and Rs. 500/- for the helper.

However, the supervisors and other higher officials are government

employees.

The anganwadis are meant to provide the following services:

-

supplementary nutrition to children below 6 years of age, and nursing and pregnant mothers from low income families

-

nutrition and health education to all women in the age group of 15- 45 years

-

immunisation of all children less than 6 years of age and immunisation against tetanus for all the expectant mothers

-

health check up, which includes antenatal care of expectant mothers, postnatal care of nursing mothers, care of newborn babies and care of all children under 6 years of age

-

referral of serious cases of malnutrition or illness to hospitals, upgraded PHCs/ Community Health Services or district hospitals

-

non-formal preschool education to children of 3-5 years of age.

By many accounts, thus far the scheme has been a success. Most of the studies conducted on the functioning of the ICDS Scheme have recognised its positive role in the reduction of infant mortality rate, in improving immunisation rates, in increasing the school enrolment and reducing the school drop out rates. The most important impact of the Scheme is clearly reflected in significant declines in the levels of severely malnourished and moderately malnourished children and Infant Mortality Rate in the country. The percentage of children suffering from severely malnutrition declined from 15.3 per cent during 1976-78 to 8.7 per cent during 1988-90. Infant Mortality Rates declined from 94 per 1000 live births in 1981 to 73 in 1994.

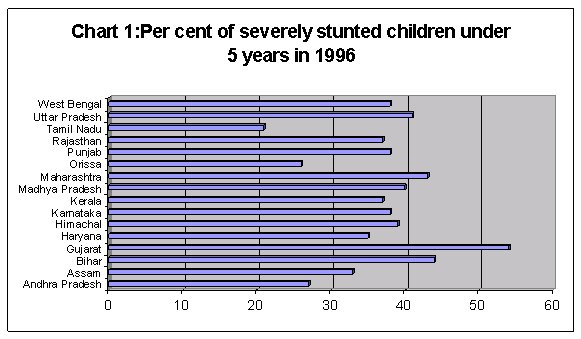

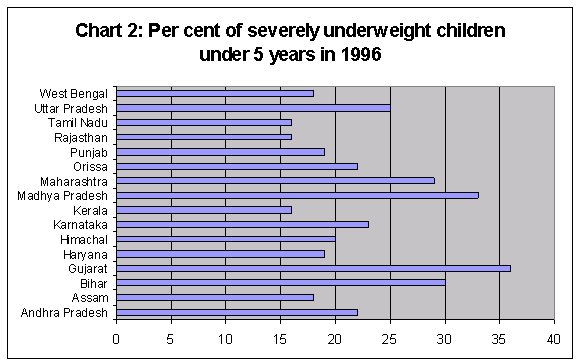

Nevertheless, it is also clear that for a scheme that has been in operation for three decades, the benefits are still far too limited, and maternal and child health and nutrition are still areas of major concern for policy. Even today, around one third of Indian children – and more than half in rural areas - are born with low birth weight. Charts 1 and 2 indicate the extent of severe stunting and severe under-nutrition among young children in the major states, both of which are still unacceptably high. It is noteworthy that these indicators are particularly bad in some ostensibly more ''developed'' and relatively high-income states, such as Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka.

The high incidence of premature births, low birth weight and neonatal and infant mortality can be attributed to poor nutritional conditions of the mothers. The majority of women still do not get proper nutrition and health care during their pregnancy. In some areas, 60-75 per cent of pregnant women receive no antenatal care at all. More than 85 per cent of women in rural areas and 95 per cent in the remote areas give birth at home. Only 42 per cent of women in the country have access to safe delivery facilities.

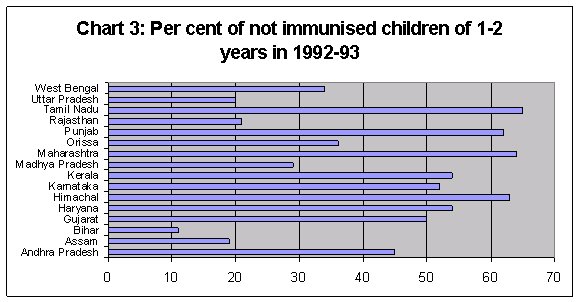

In addition, surveys indicate that even the immunisation services were still well below minimally acceptable norms in the 1990s. Chart 3 shows that most children in the age group 1-2 years were not adequately immunised.

What explains this continuing dismal picture even thirty years after

what is one of the more successful of government schemes was launched

specifically to address these problems? The basic answer must be

that not enough resources have been devoted to this scheme, to meet

the huge requirement. Quite simply, there are not enough anganwadis

or anganwadi workers, and they do not have adequate resources to

meet all the nutritional requirements of those pregnant and lactating

mother, infants and small children who need them. If the declared

norm of one anganwadi per 1000 population is to be met, there should

be 14 lakh anganwadis, as against the current 6.5 lakh such centres,

of which only around 6 lakh centres are operational.

There is the further problem of overloading the tasks assigned to

anganwadi workers. The worker and helper in such centres are paid

so little that they are no more than voluntary workers who receive

a paltry ''honorarium'', and are called ''part-time workers'' in

the centres which are supposed to open for only four hours a day.

Yet they have been found to be among the most dedicated and committed

of public servants who have developed grassroots contacts and are

able to identify particular individuals and groups in any community

easily. They are therefore increasingly engaged in a wide range

of other public interventions, especially in the rural areas.

Some of these other jobs in which the anganwadi workers and helpers

are involved relate to Health Department services such as creating

awareness on diarrhoea and ORS, Upper Respiratory Infections, Directly

Observed Treatment System for Tuberculosis, AIDS awareness, motivation

and education on birth control methods, etc. There are also additional

activities related to the Education Department like Total Literacy

Programmes, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, DPEP, Non Formal Education, etc.

In some areas, the close relationship that develops with the local

women makes these women insist that the anganwadi workers accompany

them to the hospital when they go for family planning operations,

their children’s illness, and so on. It is easy to see that all

this amounts to more than a full-time activity, yet the anganwadi

workers and helpers are hardly compensated for all this. In any

case there are simply not enough of them to cater to all of these

varied demands even within a small population.

There are other problems which stem directly from this inadequacy

of centres, staff and resources to run this programme effectively.

It has been found that one of the primary reasons for poor coverage

of needy groups under the scheme is the location of the anganwadi

centre, which typically tends to be in the main village or in upper

or dominant caste hamlets in rural areas in most states. This restricts

the access to such services by deprived communities such as SCs

and STs who live slightly apart. Yet these are precisely the groups

who require it the most.

The expenditure for running the ICDS programme is currently met

from three broad sources:

-

funds provided by the Centre under ‘general ICDS; used to meet expenses on account of infrastructure, salaries and honorarium for ICDS staff, training, basic medical equipment including medicines, play school learning kits, etc.

-

allocations made by the state governments to provide supplementary nutrition to beneficiaries

-

funds provided under the Pradhan Mantri Gramodaya Yojana (PMGY) as additional central assistance, technically to be used to provide monthly take home rations to those children (age group 0 to 3 years) living below the poverty line and in need of additional supplementary nutrition.

There

are frequent complaints of the delay in central government transfer

of resources for this programme, while state governments differ

substantially in the amount and quality of supplementary nutrition

that is provided. This makes the Scheme uneven and sometimes even

problematic in terms of the quality of food provided and its acceptability

to small children.

The original intent of the ICDS programme was to address the various

sub-stages (conception- 1 month, < 3 years and 3-6 years) of

growth in order to ensure that negative health and nutritional outcomes

do not accompany the child from one stage to the next. However,

it has been pointed out by many researchers that the way the programme

has been implemented, it effectively ends up concentrating mainly

on the 3-6 years age group. While children under 3 years are usually

enrolled in the programme, their involvement remains nominal and

there are no facilities to allow for reaching out to such children

and their mothers at home in an effective way.

The timing of the anganwadi centres also effectively rules out many

of the poorest households, since they are open only for four hours

a day. When both parents are working, which is typically the case

among rural labour households in many parts of the country, it is

difficult to deliver and pick up the child from the centre in time,

and so children in such households get excluded from the services.

Once again this really boils down to a question of resources, since

these centres should be open for longer with higher associated expenditure.

These problems have long been recognised, and public interest litigation

(especially by the People’s Union for Civil Liberties, among others)

has ensured that some important orders have been passed by the Supreme

Court in this regard. In 2001, the Supreme Court directed the State

Governments and Union Territories to implement the ICDS in full

and to ensure that every ICDS disbursing centre in the country provide

300 calories and 8-10 grams of protein for each child up to 6 years

of age; 500 calories and 20-25 grams of protein for each adolescent

girl; 500 calories & 20-25 grams of protein for each pregnant

woman and each nursing mother; and 600 calories and 16-20 grams

of protein for each malnourished child. The Court also ordered that

there should be a disbursement centre in every settlement.

Despite this court order, the government was slow to act and very

little was done to ensure that these demands were met even four

years later. However, in the latest Budget Speech of the Finance

Minister, the following promise has been made: ''The universalisation

of the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme is overdue.

It is my intention to ensure that, in every settlement, there is

a functional anganwadi that provides full coverage for all children.

As on date there are 6,49,000 anganwadi centres. I propose to expand

the ICDS scheme and create 1,88,168 additional centres that are

required as per the existing population norms. Forty seven per cent

of children in the age group 0-3 are reportedly underweight. Supplementary

nutrition is an integral part of the ICDS scheme. I propose to double

the supplementary nutrition norms and share one-half of the States’

costs for this purpose. I also propose to increase the allocation

for ICDS from Rs.1,623 crore in BE 2004-05 to Rs.3,142 crore in

BE 2005-06.''

This appears very positive, but it is immediately evident that this

is still well below the requirement and that even the additional

centres will still not meet the declared population norms. Quite

clearly, the required expansion, in terms of Central allocation

of resources and hiring of more workers, is much greater than is

being envisaged by the Government even now.

More

significantly, the Finance Minister’s statement can be seen as a

partial attempt to meet the increasing concern of the Supreme Court,

which has already twice reprimanded the government for not doing

enough to ensure the univeralisation and greater effectiveness of

the Scheme. In the latest order, dated 7 October 2004, the Supreme

Court issued very detailed and far-reaching instructions, as follows:

''1. The aspect of sanctioning 14 lakhs AWCs and increase of norm

of rupee one to rupees 2 per child per day would be considered by

this Court after two weeks. (It was subsequently put off following

an affidavit by the Government.)

2. The efforts shall be made that all SC/ST hamlets/habitations

in the country have Anganwadi Centres as early as possible.

3. The contractors shall not be used for supply of nutrition in

Anganwadis and preferably ICDS funds shall be spent by making use

of village communities, self-help groups and Mahila Mandals for

buying of grains and preparation of meals.

4.All State Governments/Union Territories shall put on their website

full data for the ICDS schemes, including where AWCs are operational,

the number of beneficiaries category-wise, the funds allocated and

used and other related matters.

5.All State Governments/Union Territories shall use the Pradhanmantri

Gramodaya Yojna fund (PMGY) in addition to the state allocation

and not as a substitute for state funding.

6.As far as possible, the children under PMGY shall be provided

with good food at the Centre itself.

7.All the State Governments/ Un ion Territories shall allocate funds

for ICDS on the basis of norm of one rupee per child per day, 100

beneficiaries per AWC and 300 days feeding in a year, i.e., on the

same basis on which the Centre makes the allocation.

8.Below Poverty Line shall not be used as an eligibility criterion

for ICDS.

9.All sanctioned projects shall be operationalised and provided

food as per these norms and wherever utensils have not been provided,

the same shall be provided. The vacancies for the operational ICDS

shall be filled forthwith.

10. All the State Governments/Union Territories shall utilise the

entire State and Central allocation under ICDS/PMGY and under no

Circumstances, the same shall be diverted and preferably also not

returned to the Centre and, if returned, a detailed explanation

for non-utilisation shall be filled in the Court.

11.All State/Union Territories shall make earnest efforts to cover

the slums under ICDS.

12.The Central Government and the State/Union Territories shall

ensure that all amounts allocated are sanctioned in time so that

there is no disruption whatsoever in the feeding of Children.''

These are extremely important guidelines, yet it is evident that

the government is not likely to conform to them without sufficient

social and political pressure. It is a sad commentary on the state

of public intervention, that even the most critical schemes that

are universally acknowledged to be necessary to ensure the future

of the country, must be fought for in courts of law and then insisted

upon through activism and people’s struggles.

©

MACROSCAN 2005