Themes > Features

10.06.2003

Agrarian Crisis and Distress in Rural India

Rural India is in acute

distress. Though the bulk of the population in rural India has always

experienced pitiable living conditions yet, their conditions are much

worse at this moment than perhaps at any other time since the mid-sixties

as there is not enough work, not enough food to eat and not enough water

to drink for the rural population.

Those commentators who at all bother to notice the state of affairs, and

they are few and far between, attribute this distress to the prevailing

conditions of drought, which gives the impression, that it is a transitory

phenomenon, and that it is a curse of nature. In reality however, the

drought compounds the distress of the rural population as the increasing

distress of the past several years has left them without any cushion.

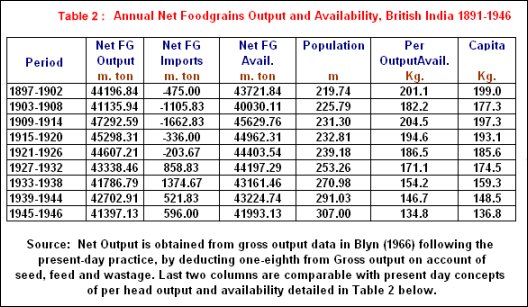

The magnitude of distress can be gauged from the two Tables given below

(both taken from Utsa Patnaik, ‘Foodstocks and Hunger’ mimeo.). The 1990s

have not only seen a steady decline in the level of per capita food

availability in the country as a whole (taking both rural and urban India

together); the absolute amount of per capita food availability in the year

2002–03 was even lower than during the years of the Second World War-years

that saw the terrible Bengal famine. Since urban India, on average, has

not seen any drastic decline in food availability, the actual situation in

rural India, it follows, must be even worse than what these figures

suggest. And this situation, it must be emphasized, does not take into

account the onset of the current drought. The drought has only accentuated

a state of distress in rural India that has been growing ever since the

1990s, that is, ever since the country has embarked on the programme of

neo-liberal economic reforms.

Apologists for the neo-liberal policies put forward a curious argument to

explain the decline in per capita food availability. This decline, they

contend, is because of a change in the dietary habits of the people: they

have diversified their consumption pattern from foodgrains towards all

kinds of less-elemental and more sophisticated commodities. Therefore,

according to them, far from its being a symptom of growing distress, the

decline in food availability is actually indicative of an improvement in

the conditions of the people, including the rural poor. Some have even

gone to the extent of suggesting that with the changes occurring in Indian

agriculture in terms of the cropping pattern and use of machinery,

peasants and workers do not need to put in hard manual labour.

Correspondingly, the need for consuming huge amounts of foodgrains no

longer arises. Therefore, the rural population now is no longer bound to

follow the old consumption pattern; it can afford to sample more up-market

goods, including food items, which it is doing with a vengeance.

The dishonesty of this argument is quite appalling. All over the world,

and all through history, as people have become better off they have

consumed more foodgrains per capita, not less. True, this increase in

foodgrain consumption per capita with increasing per capita incomes does

not take the form of larger direct consumption of foodgrains; it

takes the form of larger indirect consumption, so that taking

direct and indirect consumption together the per capita consumption of

foodgrains increases with rising incomes. In other words, people do not

consume more corn or more cereals per se. They consume, more

poultry products, meat and processed foods but the animals in turn consume

more foodgrains, so that people, directly and indirectly, consume

more foodgrains per capita. Thus in the former Soviet Union the annual per

capita consumption of foodgrains, both directly and indirectly, was as

much as 1 ton. This does not mean that a Soviet citizen actually consumed

1 ton of foodgrains per year; he or she consumed only a fraction of it

directly and the rest via larger animal products and processed foods.

Likewise in the US today the annual per capita consumption of foodgrains,

both direct and indirect, comes to about 850 kilograms, which is six times

the Indian figure of availability (the availability figure for

India today is likely to be larger than the consumption figure since the

former includes consumption plus additions to private stocks and

such additions must be occurring at a time when public foodgrain stocks

are burgeoning).

Within India too when we look at cross-section data across states, it is

clear that states with higher per capita incomes have higher per capita

consumption of foodgrains, that is, foodgrain consumption rises with

income. What is true, and is invariably dragged into the argument by

neo-liberal apologists, is that, according to NSS data, per capita

consumption of foodgrains is declining over time for all income groups,

which is supposed to support the ‘changing tastes’ hypothesis. But, in the

case of the higher income groups, this finding loses its relevance because

indirect consumption of foodgrains via processed foods etc. is

systematically underestimated by the NSS. When we bear in mind the

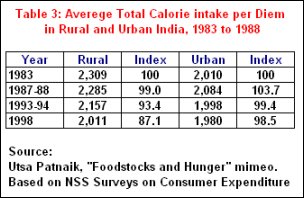

additional fact that the per capita calorie intake has gone down

drastically for the entire rural population (see Table 3), and hence is

likely to have gone down even more drastically for the rural poor, the

fact of growing rural distress stands out in bold relief.

This growing distress has occurred precisely during the very years when

the country has accumulated enormous foodstocks; indeed these two

phenomena are the two sides of the same coin. The fact that accumulation

of such enormous foodstocks has occurred despite a stagnation (or even a

marginal decline) in per capita foodgrain output in the country during the

1990s (see Table 1), suggests that the cause of this accumulation is the

absence of adequate purchasing power of the rural population. In other

words, the period of neo-liberal reforms has seen a significant

curtailment of purchasing power in the hands of the working people,

especially in rural India, which has caused growing distress on the one

hand and an accumulation of unwanted foodstocks in the hands of the

government on the other. The fundamental cause of the growing rural

distress is income deflation in rural India.

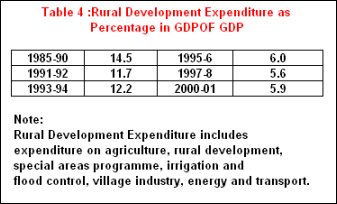

The most obvious and basic cause of this income deflation is the cut in

government expenditure in rural areas. Table 4 gives figures of rural

development expenditure as percentage of GDP.

The decline, especially

after the mid-nineties is quite drastic. Public expenditure is an

important source of employment generation in rural India. A number of

well-meaning commentators, seeing that the bulk of public expenditure,

including even the expenditure which is meant to benefit the rural poor,

gets into the hands of the rural rich, often come to the conclusion that

the curtailment of such expenditure would have little adverse effect on

the rural poor. This is erroneous. No matter to whom the expenditure

accrues in the first instance (and of course it is an exaggeration to say

that all of it gets into the hands of the rural rich), its multiplier

effects do generate jobs for the rural poor. The cessation of such

expenditure therefore negatively affects them. And this is exactly what

has happened. Perhaps the most important source of injection of purchasing

power into rural areas has dried up under the impact of the neo-liberal

economic 'reforms' that have brought in their train acute fiscal crisis of

the state. In the miasma of confusion that constitutes the so-called

'State versus Market' debate (as if the pro-market reforms entail a

'withdrawal of the State' as opposed to a harnessing of the State for

their own benefit by international finance capital and its local allies),

what is particularly striking is the fact that the role of public

expenditure in generating employment, especially in rural areas, scarcely

ever figures. But that is symptomatic of an even deeper malaise, namely

that rural India, especially the rural poor, have completely disappeared

from the official economic discourse these days, except in the tendentious

statistics about decline in poverty!

The decline in rural development expenditure by the government affects

rural employment in two very distinct ways: the first, mentioned earlier,

is through its immediate multiplier effects; an injection of purchasing

power from outside dries up and this fact has a cumulative effect on

employment via an overall reduction of purchasing power that is many times

the initial reduction. Additionally however, there is another effect that

operates over time. The reduction in public development expenditure has an

adverse effect on rural infrastructure, on the availability of irrigation

and extension facilities, on the availability of cheap inputs, and so on.

All these affect the growth rate of agricultural output, and, through this

mechanism, the employment situation. (And if the decline in public

development expenditure is accompanied by a drying up of rural credit and

a reduction in input subsidies whose impact is borne by the producers,

then the effect on agricultural growth rate and employment is even more.)

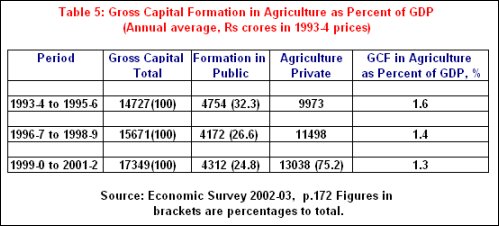

Table 5 gives figures for gross capital formation in agriculture as

percentage of GDP. The first point to note is the abysmally low share of

investment in agriculture as a percentage of GDP. Since agriculture

accounts for roughly a quarter of the GDP and since GCF accounts for

roughly a quarter of the GDP, if GCF in agriculture was to be in

accordance with this sector's overall weight, then it should have been

6.25 per cent (a quarter of a quarter). In contrast we find a figure that

is no more than a mere 1.6 per cent. What is more, even this has been

declining through the 1990s. Within investment moreover, the share of the

public sector has declined quite sharply. Now, much of private investment

goes into high value crops that have a lower employment intensity than the

more commonplace agricultural crops, notably foodgrains, that benefit from

public investment on irrigation, infrastructure and such like. It follows

that the decline in public investment has had an adverse impact on

agricultural employment via lowering growth rate not only of agriculture,

but also of the employment-intensive crops within it. This is quite

separate from its immediate demand-side effects.

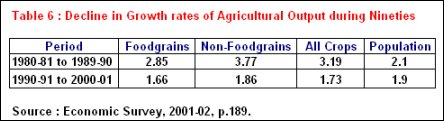

The confirmation for a reduction in the growth rate of

the more common crops, including foodgrains, is provided by Table 6.

Not only has there been a remarkable decline in the rate of growth of

agricultural output, but this rate of growth, whether of agriculture as a

whole or of foodgrains, has fallen well below the rate of growth of

population in the 1990s while it had exceeded the rate of growth of

population in the 1980s. The 1990s were indeed the first decade since

independence when per capita foodgrain output in the country declined in

absolute terms. The fact that despite this decline the country still faced

a massive accumulation of surplus foodgrain stocks shows the extent of the

squeeze on rural purchasing power, a squeeze arising from both decline in

growth rate itself and from the reduction in the injection of purchasing

power from outside.

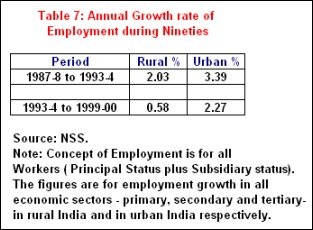

Direct evidence on employment is provided in Table 7. While the growth

rate of employment has declined in both urban and rural India in the

1990s, the magnitude of decline is much sharper in rural India. What is

more, the absolute level of the growth rate of employment in rural India

is an abysmal 0.58 percent, which is so far below the rate of growth of

rural population that one can safely infer a substantial increase in the

rural unemployment rate.

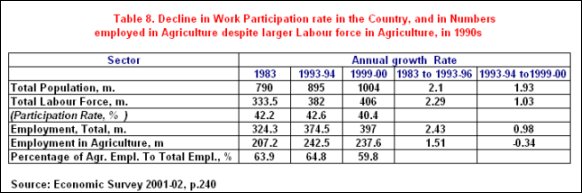

Table 8, taken from the Government's own Economic Survey, shows

another startling phenomenon, namely an absolute decline in the employment

in agriculture. The NSS figures for the same period show a slightly

different picture, namely a 0.18 per cent increase in agricultural

employment, but even this is so minuscule an increase that we can conclude

quite safely that agricultural employment in the 1990s scarcely grew at

all.

The picture of an absolute stagnation in agricultural employment and a

near stagnation in total rural employment sum up the situation of acute

distress in rural India, precisely during the 1990s when the

government-controlled media and economists on the pay-roll of the Bretton

Woods institutions celebrated the 'achievements of liberalization’.

But it was not just unemployment that plagued rural, especially

agricultural, India. In addition there was a drastic fall in prices of

cash crop, which was imported from the world market under the new

dispensation of 'liberal trade’. The price-fall in the world market in

turn was the result of the stagnation and recession in world capitalism,

which arose because, among other things, of the ascendancy of a new form

of international finance capital. This made a continuation of Keynesian

demand management of the post-war years impossible, and favoured the

imposition of deflationary measures, which are always much liked by

finance, all over the world. The price declines did not for long remain

confined to cash crops alone; even foodgrain producers have seen declining

prices in the recent years.

The drought has come on top of all this. Its effect would be a further

squeeze in the purchasing power of the rural poor leading to acute

distress. The fact of drought affecting the demand side even more sharply

than it affects the supply side would appear incredible to anyone familiar

with the history of the post-independence Indian economy. In the past, a

drought always entailed a rise in prices, affecting the rural (and urban)

workers adversely through a price inflation relative to their money wages

(or what is called a profit inflation). But now the picture is altogether

different. The effect of the drought is much greater on the demand side

than on the supply side, as a result of which while the drought brings

great hardships these are no longer reflected in the figures of inflation.

Most observers have not yet become accustomed to this phenomenon of income

deflation, which has the same effect on the living conditions of the group

whose income is being deflated as a profit inflation has, but which is a

more silent killer. A person's real earnings can be halved either through

a doubling of prices or through a halving of the money earnings. The

effect in either case is exactly the same but the former attracts greater

notice than the latter. Just a few days ago when the rate of increase of

the index of wholesale prices, which is quite low at this moment (though

that fact is of little consolation since income deflation is being imposed

upon the rural population) climbed up by a couple of decimal points

there was a hue and cry that inflation was rearing its ugly head once

again! But the much more persistent and drastic income deflation that has

been imposed on the rural working people throughout the 1990s, ever since

the programme of 'liberalization' was launched, has scarcely been noticed

at all.

Whenever this overwhelming evidence, drawn from the government's own

statistics, on rural distress is presented, the typical reaction, when all

other arguments attempting to refute it fail, is: 'If things are so bad,

why aren't people rising up?’ There are to be sure the signs of that

peculiar involuted resistance that the peasantry alone is capable of,

namely suicides, which now occur on a large scale. In addition however it

must be borne in mind that distress also saps the capacity to rise up.

Manik Bandyopadhyay in a classic Bengali short story, 'Why didn't they

snatch and eat?’, set in the context of the Bengal famine, had pointed to

this very fact. The reason why people died of starvation in millions,

often in full sight of shops and restaurants full of food, was because

they were too weak to snatch and eat. Something of the sort may well be

happening in rural India today. It is therefore the duty of the

progressive forces to instil hope, anger and the will to resist among the

distressed people of rural India.

© MACROSCAN

2003