Cotton and International Trade: Unfair Prices for the Developing World

In

the post WTO era, ever since agriculture was opened

up to free global trade, world prices of cotton have

witnessed a sharp and steady decline. Despite the

avowal to cut protection in agriculture, the post WTO era has not seen any reduction in protection that

is being given to farmers in rich developed countries

like the US and the European Union. The subsidies

given by the US to its cotton farmers have largely

been accepted to be the reason for the spectacular

decline in cotton prices at a global level.

The reason for this is that since the government provides

a large range of domestic support, US cotton farmers

increase their production unlimitedly and in much

excess of domestic demand. This excess is then dumped

in the international market, which makes the world

cotton supply much larger than demand and brings down

cotton prices. This is possible since the US has various

export promotion programmes like credit promotion

and other direct payments for making US cotton globally

competitive, which, though disguised as non-subsidies,

actually help to dump this surplus in the international

market. Some of it is given as compensation to US

farmers if their actual price is higher than the world

price (See step 2 payments in

the box below). This obviously encourages the

US producer to dump a huge supply on the international

market. Not surprisingly, world prices have declined

steadily since 1995 and reached a 29 year low in 2001.

While Cotton prices have declined by more than 60

percent since 1995, U.S. subsidies to its 25,000 cotton

farmers reached 3.9 billion dollars in 2001-02, double

the level of subsidies in 1992. Interestingly, the

value of subsidies provided by American taxpayers

to the cotton barons of Texas and elsewhere in 2001

exceeded the market value of output of cotton by around

30 per cent. In addition, this subsidy is provided

to only the richest 10% of US farmers who get 73%

of the total cotton subsidies. The rest of the cotton

farmers in America hardly benefit from these subsidies.

This actually shows that US subsidies, though largely

domestic, is actually for the benefit of the export

market.

|

World Production of Cotton

Between 1998-99 and 2002-03 the US has increased its

production at an annual rate of 5.45% (Table 1). It

reached its peak in 2001-02, producing a staggering

20, 303 thousand bales of cotton. Interestingly, its

surplus of production over domestic demand has also

increased steadily from 3,517 thousand bales in 1998-99

to 9,909 thousand bales in 2002-03. This is close

to a three-fold increase in surplus levels over a span

of just 4 years and represents a 29.56 % annual growth

rate. Stocks show a much lower growth rate of 8.70%

per annum. This is not surprising since the huge production

is dumped into the export market. World production

also shows a huge increase between 1998-99, and 2001-02

when it reached peak levels. From a figure of 85,

298 thousand bales in 1998-99, it went up to 98,463

bales in 2001-02.

|

|

A look at table 1 shows that the US has increased

its export market share drastically between 1998-99

and 2002-03. From a share of 18.16% in 1998-99, America’s

share in world exports jumped to 38.96 % in 2002-03.

This represents a huge annual average growth rate

of 28.99% between these two years. Obviously, nudged

on by its subsidy programme, US exports have been

able to keep pace with its surplus growth rate.

Only in the last two years does the US show a decline

in production and a subsequent decline in World production

has generated a surplus of use over production, resulting

in an increase in world prices.

Global Prices of cotton and

the US

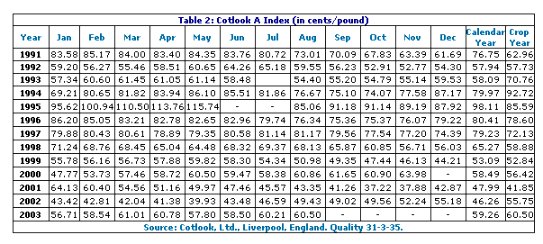

In 2001-02, global prices were around 42 cents per

pound, the fourth year in succession that they were

below the long-term average of 72 cents per pound

(Table 2). Even the most efficient producers are now

operating at a loss, unable to cover the costs of

production. Marketing projections by the International

Cotton Advisory Committee (ICAC) suggest that prices

will remain chronically depressed in the foreseeable

future. Forecasts point to a modest recovery in 2003,

but prices look likely to remain at between 50-60

cents per pound until 2015 if present conditions continue.

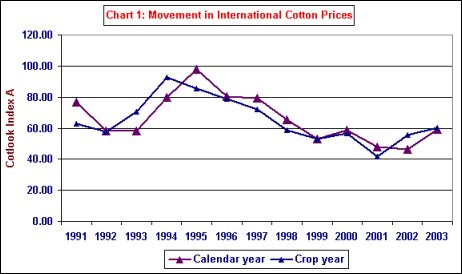

Table 2 and Chart 1 show the spectacular decline in

the Cotlook Index A, the indicator for the global

prices of cotton. The annual indices according to

both calendar and crop year (the latter is the more

relevant timeframe) reflect this pattern. However,

only in the last one-two years have there been some

improvement in the global prices of cotton. That is

largely because of the fact that due to the rock-bottom

price in 2001-02, global stocks had been drawn down

subsequently. But unless the subsidies are cut soon,

the imbalance in the world market will continue.

|

|

|

|

Since it has managed

to bring in such a large supply, the subsidies given

by the US government has brought down international

prices considerably. Consequently, after 1995 when

the Agreement on Agriculture came into effect, global

prices continued to fall reaching the lowest ever

level in 29 years in 2001. It is not surprising, and

only goes to prove the trade distorting nature of

US subsidies, that this all-time-low in global prices

coincide with the highest level of US subsidies in

2001-02. The subsidies managed to bring the largest

ever supply of cotton by US farmers to the export

market around 2001 and 2002.

This price pattern is ironical considering agricultural

prices were supposed to increase after the Agreement

on Agriculture. A less protected international agricultural

market and the removal of subsidies by the developed

countries were supposed to improve cotton prices and

therefore improve the lot of poor farmers in poorer

countries. However, the reality turned out to be rather

different.

The Developing World

Estimates by the International Cotton Advisory Committee

(ICAC), using its World Textile Demand Model, indicate

that the withdrawal of American cotton subsidies would

raise cotton prices by 11 cents per pound, or by 26

per cent.

The refusal to cut cotton subsidies by the US has

adversely affected the condition in many developing

or least developed countries, which are exporters

of cotton. The government of India puts its losses

at $1.3 billion, Argentina at over $ 1 billion, and

Brazil at $ 640 million in 2001-02. However, countries

located in Africa, especially Benin, Burkina Faso,

Chad and Mali, who depend heavily on cotton exports

for their economic conditions, have been hit the hardest

by the secular decline in prices. In 11 countries

in Africa, cotton export earnings bring in one fourth

of all export revenue. In the four above-mentioned

African countries, 30 per cent of total export earnings

and over 60 per cent of earnings from agricultural

exports come from cotton. According to Oxfam, U.S.

cotton subsidies are destroying livelihoods in Africa

by encouraging over-production and product dumping.

According to an Oxfam Report (2001), costs of production

for one pound of cotton are three times higher in

the US than in Burkina Faso. Other major producers

like Brazil also have far lower production costs.

In spite of this, the US has expanded production in

the midst of the price slump. Obviously cotton subsidies

help them to increase production unlimitedly, and

then dump that higher production in world markets.

Other countries have consequently suffered as a result

of both lower prices for exports and loss of world

market share. While the US improved its share gradually

to a massive 40% of the world market, other major

exporters who could not subsidies their exports suffered

a decline. Uzbekistan’s share dropped from 16.11%

to 11.46%, and that of Mali from 4.01% to 2.78% between

1998-99 and 2002-03. In fact this decline had started

even earlier. Burkina Faso’s share increased

marginally but it lost out in real terms due to the

steady decline in global prices of cotton.

For India, the subsidies mean a huge loss. Though

India is a net importer at the moment, and therefore

Indian consumers can take advantage of the price

decline, Indian farmers are losing out heavily.

Imports are flooding the Indian market, whereas if

subsidies were cut, Indian cotton could have become

much more competitive. The trend of international

prices over the last few years has driven many of the

poorer and smaller cotton farmers to suicide. This

phenomenon has taken on alarming proportions since

most of the farmers who have gone into cotton

production have had to take heavy loans in order to

meet production needs. However, regular slumps in

international prices have meant that they were unable

to capture enough of the world market, nor able to

recover enough profits to be able to repay their loan.

Simultaneously and more crucially, they are forced to

compete with international cotton supply even in the

domestic market.