And,

of course, matters are much worse considering only

those crops whose data is firm. Although current estimates

of foodgrain production for 2003-04 are a whopping

19% higher than in 2002-03, this is only 4% higher

than in 1998-99; and the overall Index of Agricultural

Production (IAP) has increased less than 3% between

1998-99 and 2003-04. The IAP per capita of rural population

is thus actually down 6% from 1998-99 while per capita

foodgrains output is down 5%.

Moreover, this is not all. The feature that distinguishes

the last five years, and worries farmers most, is

that farm prices have drifted relatively lower despite

low output growth. With agricultural GDP at current

prices shown 27.3% higher in 2003-04 than in 1998-99

against 10.4% increase at constant prices, agricultural

prices increased 15.4%. But during the same period,

non-agricultural GDP is estimated to have increased

39.2% in constant prices and 69.1% in current prices,

implying 21.5% increase in non-agricultural prices.

The GDP estimates imply at least 5% terms of trade

loss for agriculture over 1998-2004.

Again, matters might be worse since official terms

of trade indices from the Ministry of Agriculture

had already shown 5% decline during 1998-2002, when

terms of trade from GDP estimates had shown only 2%

decline. But in any case, taking terms of trade into

account, the purchasing power of agricultural incomes

has actually declined in per capita terms during 1998-2004

even by the optimistic NAS figures; and this decline

is by more than 10% if one combines official Indices

of Agricultural Production and Terms of Trade. Thus,

despite some diversification, overall agricultural

outcomes have been poor, both on output and prices.

As far as output is concerned, this is because rates

of growth of yields per acre have declined very sharply

for almost all major crops. Considering all the crops

covered in the IAP, yield growth had averaged 2.5%

per annum during the 1980s, dropped to around 1.5%

by 1998-99, and has averaged only about 0.5% during

the last five years. Underlying this are some long-term

trends, e.g. the plateau reached by ‘green revolution'

technology and inadequate public investment since

the 1980s. But matters have worsened recently on these

and other fronts, such as extension and cooperative

credit, because the Fifth Pay Commission bankrupted

state governments.

Of course, some states have done better than others

on output growth and the private sector has begun

extension activities for some crops in some regions.

But, with very few winners and many losers, agricultural

production performance is not an aspect in which India

is shining. However, the political fallout is not

entirely clear since, with most states opposition

ruled, the blame-game will be about Centre-state responsibility

and response. And the debate is likely to be on whose

incumbency hurt more, not what is to be done in the

future.

On the price situation, however, the NDA is much more

vulnerable. After all, it was the Centre that caved

in at WTO and dismantled quotas prematurely, exposing

Indian agriculture to the international price volatility

that many farmers blame for their woes. And, although

attractive support prices were announced, farmers

in most regions did not actually get any price support.

Moreover, contrary to recommendations of some committees

to extend support operations, there are plans to halt

support purchases altogether and link support prices

to insurance – a misguided alternative already being

piloted in some districts where Rabi arrivals will

coincide with elections.

Turning to rural poverty, can this have reduced given

the poor agricultural outcomes? Also, given the near

vacuum on policy initiatives on agricultural production

and price instability, what are the ideas to deal

with this? The important aspect that needs noting

in this context is that rural incomes are not all

from agriculture and that fall in crop prices, although

this hurts farmers, can improve conditions for those

who buy food.

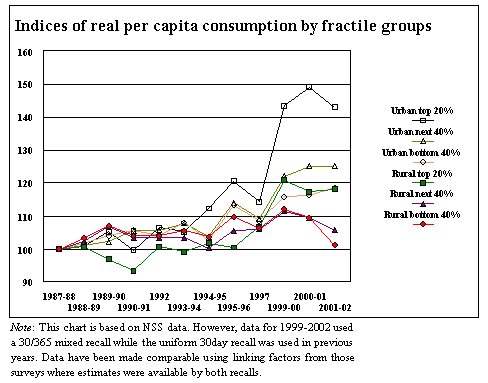

Chart

>> Click

to Enlarge

The ‘shining' campaign has put particular emphasis

on the achievement on roads and thus of rural connectivity.

And available NSS data does show fairly massive rebound

(by over 40%) in rural non-agricultural employment,

particularly construction, transport and trade, during

1997 to 2001-02, after a collapse during 1990-91 to

1997. Moreover, available data on wages and prices

show that the consumer price index for rural labour

increased less than other price indices after 1998-99

and that real wage rates have increased. Further,

rural non-food consumption is increasing whether one

goes by NSS or independent data. Thus, there are clear

signs of rural dynamism if one goes beyond agriculture.

However, paralleling the poor agricultural performance,

there is also evidence of stagnation in agricultural

employment while the number of rural workers dependent

on wage employment has increased very sharply (over

45% since 1991). NSS data in fact show a doubling

of current unemployment among usual rural workers

over the period 1997 to 2001-02. Furthermore, although

the ‘shining' campaign has correctly identified the

fairly large antyodaya grain supplies as a major achievement

of the NDA, overall per capita cereals consumption

(whether measured by availability or from NSS consumption

estimates) has declined.

This coexistence of some dynamism in rural non-agriculture

alongside declining agriculture makes it difficult

to identify exactly what is happening to overall rural

well-being. This is compounded because the only reliable

source of information on this, the NSS consumption

expenditure surveys, have become non-comparable. Pressure

from ‘reformers', stung by NSS results that showed

increased rural poverty from 1990-91 to 1998, caused

a change in the nature of the questions asked in these

surveys.

Some experimental surveys had shown that asking 365

day, rather than 30 day, questions on items such as

clothing and durable goods throws up improved distribution

and that asking 7 day questions on food returns 30%

higher food consumption than 30 day questions. So,

instead of the uniform 30 day recall used previously,

the 1999-00 NSS questionnaire was changed to only

365 day for clothing and so on and both 7 and 30 day

questions for food. Not surprisingly, this led to

much lower measured rural poverty, by almost 50 million.

Since then much has been written on comparability

of subsequent NSS data, and it is sufficient to note

that it is now agreed that rural poverty did not decrease

by anything like 50 million and that, although the

proportion of poor is likely to have declined somewhat,

the number of poor may actually have gone up. More

importantly, it is now agreed that, properly interpreted,

NSS data from 1993-94 onward show very large increase

in inequalities (see chart) – across states, between

rural and urban, and within urban areas. Moreover,

although evidence on inequalities within rural areas

is less clear, the trend towards lesser inequality

that had begun in the mid-1970s with rural development

programmes and extended public distribution has clearly

halted.

But, consistent with the divergent indications on

agriculture and rural non-agriculture discussed above,

the most interesting indication from NSS data from

1993-94 to 2001-02 is that although cultivators and

agricultural labourers have done badly, and the self-employed

in non-agriculture have also not done well, those

employed for wages or salary in non-agriculture have

done much better. In fact, salaried employment, proximity

to urban growth, and the ability to migrate emerge

as main determinants, not only of the ability to avoid

poverty but also as sources of relative affluence.

Although cultivators still dominate among the richest

20% in rural areas, the proportion among the rural

rich of affluent non-cultivators with urban connections

has increased rapidly.

This should interest those attempting to guess political

outcomes. Although caste and religion continue to

dominate networks of patronage, the combination of

poor agricultural outcomes and rapid urban growth

in recent years has shifted the rural balance from

traditional elites towards those who can offer urban

access. It is here that the BJP, traditionally much

weaker in rural than urban areas, can be the biggest

gainer. Rural India is definitely not ‘shining'. But

access to the shine that exists, which the ‘shining'

campaign has made even more apparent, is now through

networks where that party is stronger. The moot question

is whether this shift in balance merely affects how

people tell outsiders how they will vote or whether

this is so deep that it will actually show up in how

they finally vote?

On this, NDA strategists might like to mull over the

following about rural India. It remains overwhelmingly

agricultural, is about to go into elections in a year

after severe drought, and is being bombarded with

celebrations of ‘shining' without any solution being

offered for what is definitely a longer-run crisis.

There have in the past been only four years before

the current one when national income has grown more

than 8%: 1967-68, 1975-76, 1988-89 and 1996-97. These

have all followed a year of drought and all except

1975-76, when Indira Gandhi declared an Emergency,

were election years. The ruling party suffered losses

every time.