Themes > Current Issues

24.03.2009

Prices and Politics in India

Jayati

Ghosh

Price

movements are fundamentally about income distribution. When prices

of certain commodities go up faster than others, it implies reduced

real incomes of those who sell the latter. The most obvious direct

effect is of course on real wages - because when the price of labour,

or money wages, does not keep pace with the items that form the consumption

basket of workers, it implies reduced real wages of workers. But other

categories of workers are also affected: when agricultural crop prices

do not go up as much as input costs for cultivation, or other goods

that farmers have to buy, it affects the real incomes of farmers.

Similarly for non-agricultural petty producers, who can also be considered

as self-employed workers.

That is why prices are also political, or rather, why inflation can

be such a hot political issue especially before elections. The general

perception is that high inflation is unpopular, for the obvious reason

that it cuts into the real income of most people. Therefore, in the

middle of last year when the increase in prices had become an issue

of widespread concern, it essentially reflected the concern that this

was impacting on the real incomes of most ordinary people.

The recent decline in inflation rates - on which more below - has

led many to believe that this is no longer a concern. But in terms

of political impact, what needs to be examined is the extent to which

inflation of the past few years has affected real incomes. In other

words, do people feel better or worse off than they did five years

ago when the UPA government came to power?

It is important in this regard to be aware of the difference between

inflation and price levels. Inflation refers to the change in prices,

and any positive rate of inflation, however low, indicates that prices

are rising. So even if the inflation rate is coming down, that does

not mean that prices are coming down, it only means that prices are

increasing at a slower rate than before. This is a mistake commonly

made by media commentators, who confuse a decline in inflation rates

with a decline in prices. If prices themselves actually come down,

then that is deflation.

Why does this matter? Because even if the inflation rate slow down

or comes down to zero, it simply means that the price level stays

at the level it had reached, which may be felt to be a very high level

by those whose nominal incomes have not increased. So if prices had

risen very dramatically last year, but have now slowed down, this

may still be experienced as very high price levels by those whose

wages and salaries have not increased much over the whole period.

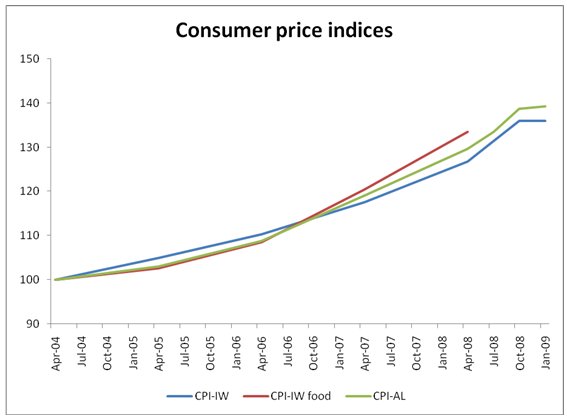

The accompanying chart shows how consumer prices - the price of the

basket of goods estimated to be consumed by different groups of workers

- have moved since April 2004, just before the last general elections.

Some points of note emerge from this chart. First, overall inflation

has been quite high for both sets of workers over this period, with

consumer prices increasing by around 40 per cent over this five year

period. It is extremely unlikely that nominal wage incomes for most

workers in urban or rural areas have increased by that much in this

period, although we will have to wait for large sample survey data

before we can check on this. Certainly the large sample survey data

suggested little change in nominal wage and self employed incomes

between 1999-2000 and 2004-05, especially in the informal sector.

It is likely that this trend has continued into the past five years

as well. For a significant proportion of self-employed workers such

as home-based workers, micro case studies suggest that nominal remuneration

has even declined in recent times, suggesting that real incomes have

plummeted quite dramatically.

Second, while the consumer price index for industrial workers was

increasing more rapidly until October 2006, thereafter the index for

agricultural labourers has been moving up more rapidly. The main reason

is probably the faster increase in the price of food, since the food

index even for industrial workers has moved up more rapidly since

October 2006.

But higher inflation need not always be the greater problem - in fact,

sometimes the opposite can be true! This is not always and inevitably

the case - it depends on what is happening to nominal incomes as well.

So even falling inflation can be of concern, if the nominal incomes

of enough people fall even faster. And deflation, if is associated

with declining economic activity and employment, can be really bad

news.

That is why the news, on 19 March, that the wholesale price index

(WPI) for all commodities had barely increased on an annual basis,

increasing at the historically low rate of 0.44 per cent, gave rise

to mixed reactions. Some welcomed it, feeling that it reflected an

easing of the inflationary pressures that seemed so marked just a

few months ago, in the middle of last year. Others (notably the Chairman

of the Prime Minister's Economic Advisory Council) dismissed the lower

inflation rate as nothing but “a base effect” of the earlier high

prices, as the economy stabilises at those price levels. Others were

actually alarmed at this possible sign that the economy is entering

a deflationary phase, in which output and employment may even shrink.

Yet hardly any commentators dwelt on the income distribution aspect

of the inflation, which is arguably the most significant consequence,

at least politically. To understand the distributive implications,

the overall inflation rate has to be unpackaged into its component

parts, to understand which sectors and which categories of producers

and consumers are affected in different ways.

An examination of the disaggregated changes in the latest WPI numbers

throws up some surprising, even alarming, results. The accompanying

table provides information on year-on-year percentage changes (or

annual inflation rates) for different categories of goods.

Table

1: Percentage change in prices between 8 March 2008 and 7 March

2009 |

|

Category

|

Per cent change |

| All commodities |

0.44 |

|

Food articles |

7.35 |

|

Foodgrains |

10.24 |

|

Cereals |

10.16 |

|

Pulses |

10.97 |

|

Fruits & vegetables |

5.13 |

|

Eggs meat & fish |

3.89 |

|

Edible oils |

-9.78 |

|

Other food articles |

21.60 |

|

Non-food primary articles |

-1.72 |

|

Fibres |

1.73 |

|

Oilseeds |

-5.23 |

|

Minerals |

-1.21 |

|

Fuel, power light & lubricants |

-0.75 |

|

Manufactured products |

1.32 |

|

Food products |

6.03 |

|

Beverages & tobacco |

8.96 |

|

Drugs & medicines |

4.45 |

|

Textiles |

8.41 |

|

Wood & wood products |

10.05 |

|

Paper & products |

4.77 |

|

Leather & products |

1.82 |

|

Rubber & plastic products |

2.32 |

|

Chemicals & products |

1.61 |

|

Fertilisers & pesticides |

5.13 |

|

Non-metallic mineral products |

2.16 |

|

Cement |

1.22 |

|

Metals & metal products |

-11.47 |

|

Iron & steel |

-16.65 |

|

Non-ferrous metals |

-10.49 |

|

Machinery & machine tools |

2.56 |

|

Transport equipment |

2.69 |

While

overall inflation has indeed slowed down to almost no change in the

aggregate price level, food prices have continued to increase. Food

grain prices have gone up the most - by more than 10 per cent - and

this cannot be blamed on higher procurement prices alone, since the

prices of pulses, which are not covered by public procurement, have

also gone up just as much. The prices of fruits and vegetables and

eggs, fish and meat have also increased, even if not by as much as

for food grains. The only food category for which prices have fallen

is edible oils, which reflects the decline in oilseed prices as world

prices have crashed. Other food articles' prices have increased by

more than one-fifth in this one year.

So all householders who wonder how inflation could be falling when

they keep facing higher prices when they go to the market are right

in one important respect - food prices are indeed still rising, despite

the stability of the overall price level. And this will obviously

affect household budgets, especially among the poor for whom food

still accounts for more than half of total household expenditure.

It is worth remembering that food prices have always been politically

sensitive: there are elections that are supposed to have been won

or lost over the price of onions...

Another major item of essential consumption has also increased in

price: that of drugs and medicines has gone up by 4.5 per cent, which

obviously impacts upon the entire population, but especially the bottom

half of the population who may find it extremely difficult if not

impossible to meet such expenditures in times of stringency.

But these are not the only disturbing things about the disaggregated

data. A remarkable feature is how non-food primary product prices

have moved. The prices of fibres - mainly cotton, jute and silk -

have barely increased at all. Oilseed prices have fallen by more than

5 per cent. This immediately affects all the producers of cash crops,

who will be getting the same or less for their products even as they

pay significantly more for food. They are also paying more for fertiliser

and pesticides, whose prices have increased by more than 5 per cent.

Meanwhile, several manufactured goods have also declined in price

over the past year. Some of the sharpest price declines have occurred

in iron and steel (a decline of nearly 17 per cent) and non-ferrous

metals (a decline of nearly 11 per cent). This has happened mostly

in the very recent period, as the impact of the global recession fed

into trade prices. Indeed, the sheer rapidity and extent of the price

changes for traded goods is remarkable.

For example, the price of fibres rose by 12.1 per cent between 8 March

2008 and 10 January 2009, and then plummeted by 9.3 per cent in just

the past two months. While some of this can be explained by seasonality

(such as the cotton harvest that comes around December-January) the

decline this year is much sharper than previous years and reflects

international prices as well. Overall, the price index of manufactured

goods increased slightly by 2 per cent until 10 January, and subsequently

fell by 0.65 per cent to 7 March 2009.

What does all this add up to? What it suggests is a worrying combination

of falling prices faced by agriculturalists who produce cash crops

as well as petty producers and others who produce manufactured goods,

even as the prices of essential items like food and medicines continue

to rise. These groups and their families alone account for the majority

of the population in the country. The latest figures ought to worry

the government that is still in power, for this combination could

amount to electoral dynamite.

© MACROSCAN 2009