Though

still remote and unintelligible to the ordinary citizen,

the annual statement on and quarterly reviews of monetary

policy by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) receive

much attention from the Finance Ministry, the financial

sector and the media. This is not surprising given

the increased importance of the financial sector and

the crucial role of credit in the current process

of growth of the Indian economy. Most often these

periodic releases are long on analysis and short on

new initiatives. Even when circumstances are changing

rapidly, the RBI seems to err on the side of stability

rather than change.

This is also true of the assessment of Macroeconomic

and Monetary Developments and Review of Monetary Policy

for the first quarter of 2007-08, released end-July.

They reiterated concerns that have been expressed

by the central bank for some time now: about the rapid

and excessive inflow of foreign capital and consequent

accumulation of foreign exchange reserves, the resulting

overhang of liquidity in the system, the massive expansion

of credit that this excess liquidity has facilitated,

and the increasing direction of such credit to risky

or "sensitive" sectors, especially housing

and real estate.

The evidence seems to indicate that some of these

trends have only gathered momentum during the first

quarter of 2007-08. Thus, over the four-month period

between end March and 27 July 2007, India's foreign

exchange reserves rose by $26 billion as compared

with $61 over the year-ending 27 July as a whole.

This would have had collateral implications for the

other variables of concern mentioned above. Yet, the

RBI chose to be cautious in terms of new policy initiatives.

It raised the cash reserve ratio requirement, or the

deposits that banks have to hold at the central bank,

by just 50 basis points or half a percentage point

(from 6.5 to 7.0 per cent) and withdrew the ceiling

of Rs.3000 crore on daily reverse repo transactions

that permits banks to park funds with the central

bank at a specified interest rate. While the former

is expected to drain around Rs. 16,000 crore from

the financial system, the latter too may limit liquidity

to some extent.

However, given the current state of liquidity in the

system, these are by no means large sums that would

severely restrict the supply of credit relative to

demand. They are expected to only have a marginal

effect on interest rates paid to depositors, to make

up for the larger proportion of low-interest cash

reserves that the banks would have to hold. Not surprisingly,

Finance Ministry mandarins and financial sector executives

heaved a sigh of relief at the decision of the RBI

to opt for a minor mid-course correction in policy.

The RBI has merely signaled that credit must be restrained,

but has done very little in pursuit of that objective.

Moreover, the RBI has suggested that even this limited

effort to impound liquidity is driven primarily by

the need to hold headline inflation at below 5 per

cent and reduce it to the 4-4.5 per cent range in

the medium term. That is, while there are references

to credit quality, financial stability and global

dangers in the policy statement, the response of the

central bank is explained by the need to add monetary

policy measures to the government's supply management

efforts to curb inflation. The positive response of

the financial sector to the RBI's measures is also

explained by the fact that the central bank has emphasized

this objective rather than focusing on its concerns

with regard to excessive credit growth, poor credit

quality and overexposure in stock and financial markets.

The fear that the RBI may act on these concerns explains

why the quarterly monetary policy reviews and the

monetary policy changes that accompany them, have

been the target of special attention. Different interests

fear this possibility for varying reasons. The Finance

Ministry has concerns of its own making. Fiscal reform

of the kind pursued by the ministry has involved a

combination of tax concessions, lower tax rates and

a reduction in the fiscal deficit relative to GDP.

This has meant that even though rising corporate profits

and top-decile incomes have helped raise the tax-GDP

ratio, the ministry has found itself unable to meet

the commitments which the present government has made

with regard to sectors such as agriculture. The way

in which the Finance Minister has dealt with the problem

is to persuade the banking system to increase credit

provision to that sector. Part A of recent budget

speeches are full of off-budget promises to increase

credit to agriculture or even for financing private

educational expenditures. Not a day passes without

the Finance Minister congratulating himself and his

government for increasing credit provision to agriculture

in recent months, even if much of that credit is not

directed at farming per se. In the event, one fear

that afflicts Finance Ministry mandarins is that any

effort on the part of the RBI to curb credit growth,

would limit their ability to use public sector banks

as cash cows that partially make up for the government's

inability to mobilize resources for public investment.

The second reason why the Finance Ministry and the

private sector await with apprehension the RBI's monetary

policy statements is that easy liquidity, low interest

rates and expanding credit provide the basis for the

boom in India's manufacturing sector and in the real

estate and financial markets. Credit-financed purchases

of automobiles and durables, investments in housing

and real estate and forays into the stock market are

what keep the surge in the respective markets going.

If the central bank chooses to either squeeze liquidity

and credit or raise interest rates, the unusual and

consistently high rate of GDP growth being recorded

by the economy over the eight quarters beginning with

the fourth quarter of financial year 2004-05 and ending

in the third quarter of 2006-07, is likely to falter.

A third factor explaining apprehensions about possible

central bank intervention is the RBI's own expressions

of concern about structural shifts that have been

occurring in the direction of credit, in particular

to the housing and real estate markets. During 2006-07,

housing and real estate loans grew by 25 and 70 per

cent respectively, despite having decelerated relative

to their growth in the previous financial year. Further,

even though direct incremental exposure of the banking

system to the stock markets seems to be declining,

there appears to be a sharp increase in investments

in mutual fund investments, indicating a substantial

degree of indirect incremental exposure to these markets.

This combination of a sharp increase in credit exposure

combined with enhanced exposure to what are considered

"sensitive" sectors, is indeed a cause for

concern for even the central bank. The RBI, therefore,

has added reason to limit credit growth and make credit

more expensive. It also needs to be more proactive

in dealing with rising risk and increased vulnerability

in the financial sector in general and the banking

sector in particular. The expectation, therefore,

was that there would be an effort, beyond mere warning

statements, to reverse these tendencies.

It must be noted, however, that the situation of easy

liquidity is not an act of commission of the RBI.

In fact, the central bank, by restricting its lending

to the government and undertaking open market operations

of various kinds, has been seeking to limit the growth

of liquidity in the system. If yet there has been

an increase in liquidity, it has been because of the

surge of capital flows into the country, that have

tied the hands of the RBI. During 2006-07, foreign

direct investment flows rose sharply to US$ 17.7 billion

from $7.7 billion in 2005-06. Cumulative net foreign

institutional investor (FII) investments increased

from US$ 45.3 billion at end-March 2006 to US$ 52.0

billion as at end-March 2007, or by close to $ 7 billion.

And, Indian corporates have been borrowing heavily

from the international market.

It is well known that to prevent an appreciation of

the rupee as a result of this surge in capital inflows,

the RBI has been buying dollars and adding it to its

foreign exchange reserves. As a result, India's foreign

exchange reserves rose from US$ 151.6 billion at the

end of March 2006 US$ 199.2 billion by end-March 2007.

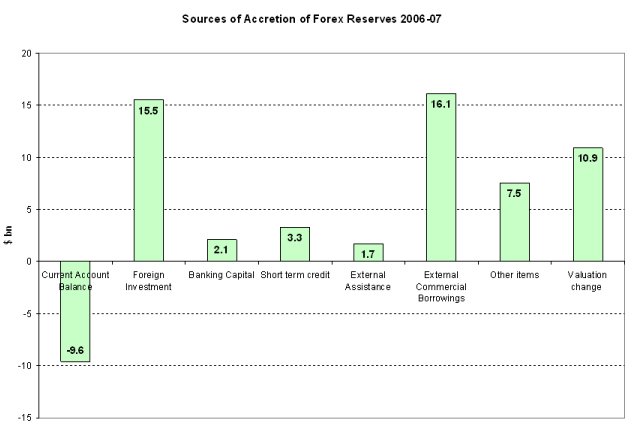

According to the RBI, of the $46.2 billion accretion

to its reserves, foreign investment accounted for

$15.5 billion, NRI deposits for $3.9 billion, short

term credit for $3.3 billion and external commercial

borrowings for $16.1 billion. In sum, external debt

of various kinds contributed to as much as $23.3 billion

to reserves in 2006-07, as compared with $7.2 billion

in 2006-07.

Chart

1 >> Click to Enlarge

This has two implications. Increases in the foreign

assets of central bank have as their counterpart an

increase in money supply, unless they are sterilized

by sales of other assets. But, having done that for

long, the Reserve Bank of India has little maneuverability

on this front. The net result has been the increase

in liquidity in the system, the consequent credit

boom and the growing exposure to sensitive sectors

and sub-prime borrowers. Both the volume of credit

and the distribution of that credit has substantially

increased risk and the threat of financial instability.

The second is that the central bank is caught in the

horns of a dilemma. If it has to manage the exchange

rate through its operations in the foreign exchange

market it would have to lose maneuverability in the

management of money supply and credit expansion. The

RBI's response to this has been such that it has not

been successful either in stalling rupee appreciation

or in reining in credit growth.

If the RBI has to be successful it would have to move

on two fronts. It would have to find ways of limiting

financial capital inflow into the country, which is

relatively easy given the rising share of external

commercial borrowing in total inflows. It would also

have to directly curb the growth of domestic credit

and the use of debt for speculative purposes by impounding

liquidity or drawing it out of the system and by hiking

interest rates to discourage debt-financed speculative

activity.

Both of these would of course squeeze liquidity and

affect the debt-financed consumption and investment

boom that explains in large part the recent acceleration

in GDP growth. It could also correct the speculative

surge being witnessed in stock and real estate markets.

Not surprisingly both the Finance Ministry and the

private sector are against such measures and have

been exerting pressure on the central bank in myriad

ways. The generalized expression of relief in the

wake of the recent monetary policy review and policy

announcement only proves that the RBI has indeed been

limited by this pressure or has succumbed to it. That

does not bode well for the future.