Themes > Current Issues

17.04.2008

Inflation:

How Much and Why

C.P.

Chandrasekhar

If

political statements and media headlines are adequate indicators, inflation

is emerging as India’s economic problem number one. Given the way prices,

especially of essentials in retail markets, have been moving in recent

months, this is hardly surprising. What is surprising is that media and

political attention to a problem that has bothered the common man for

sometime now has been rather recent.

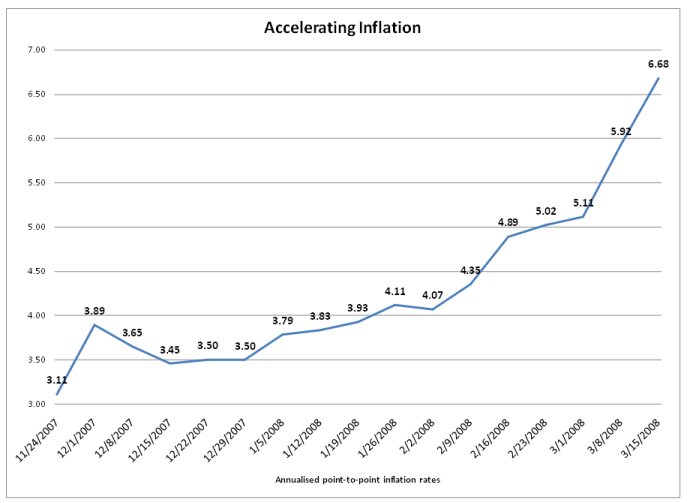

Part of the reason for this delayed response is that headline inflation figures offered by point-to-point annual increases in the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) capture trends on the ground with a substantial lag. Matters came to a head when WPI-based inflation figures relating to the week ending 15 March 2008, released at the end of last month, indicated that the annual rate of inflation had risen to 6.68 per cent, which was higher than it had been for the previous 13 months. What is more this inflation was not restricted to a few commodities but was widely spread in terms of its incidence. Inflation stood at 9.28 per cent in the case of dairy products, 19.03 per cent in the case of edible oils, 20.12 per cent in the case of oilseeds, over 9 per cent in the case of mineral oils and 26.86 per cent in the case of iron and steel. The trend has continued with the annual WPI-based inflation rate touching 7 per cent on March 22nd 2008.

The acceleration appears dramatic because going by the WPI, even as recently as February inflation was running low in the country, judged by historical standards or relative to the ceiling rate of 5 per cent set by the Reserve Bank of India. The wholesale price index for the week ended February 2, 2008 pointed to an annual inflation rate of just 4.07 per cent, whereas, during the corresponding period in the previous year annualised inflation was as high as 6.5 per cent on a week-to-week basis. However, soon thereafter the inflation rate started falling (even as concerns over inflation were still being expressed), and by October/November last year the inflation rate was hovering around the 3 per cent level. What is being witnessed now is a continuation of a trend that began in December when inflation once again edged upwards to touch 3.5 per cent in December, 4 per cent by end January 2008, 5 per cent by late February, 6 per cent at the end of the first week of March and then close to 7 per cent by mid March.

It must be noted that even a 7 per cent level is by no means high when viewed from a perspective imbued with the tolerance for single-digit inflation levels that characterised India in the past. But four factors explain the almost panic-stricken response to this rate today. First, the current level seems to be one more step in a stairway that could quickly take inflation to double digit levels. Second, the current level is well above the 5 per cent mark that has been officially declared as the acceptable ceiling rate in the wake of fiscal and monetary reform. Third, it is accepted that prices at the retail level are rising much faster and inflation as measured in terms of retail prices could be near or above double-digit levels. And, finally, all this is occurring in a period when global inflation is on the rise and policies of trade liberalisation and domestic deregulation have reduced the degree to which Indian prices are insulated from international prices.

Of these the growing distance between retail and wholesale prices is an important factor influencing the response. According to figures released by the government’s own Department of Consumer Affairs, in the last one year, in the retail market of Delhi, the price of groundnut oil has risen from Rs. 98 to Rs. 121 a kg, mustard oil from Rs. 55 to Rs. 79, vanaspati from Rs. 56 to Rs. 79, rice from Rs.15 to Rs.18, wheat from Rs. 12 to Rs.13, atta from Rs. 13 to Rs.14, gram from Rs. 32 to Rs. 38 and tur from Rs. 35 to Rs. 42. In fact, figures collated by Price Monitoring Cell of the Department of Consumer Affairs establish that in the case of a few commodities there is huge difference between inflation as measured by retail prices (collected from and averaged across 18 reporting centres nationwide) and the wholesale price index. In the case of rice, inflation over the year ending March 15 stood at 7.88 per cent as measured by the WPI, whereas it worked out to a huge 20.86 per cent in terms of average retail prices. In the case of vanaspati too the inflation rate stood at 8 and 22 per cent respectively.

These differences are bound to be reflected in the consumer price indices for agricultural labourers and industrial workers, which not only give greater weight to some of the essential commodities that have seen high rates of price inflation, but are also based on the retail prices of these commodities. Unfortunately the lag in the release of consumer price indices is much greater than in the case of the WPI, the most recent figure being for the month of February 2008. Yet, going by the consumer price indices the annual month-to-month rate of inflation stood at 6.38 per in February 2008 for agricultural workers and a much lower 4.69 per cent for industry workers. But figures based on the March indices are likely to be much higher given the most recent trends in prices revealed by other sources.

A combination of domestic and international factors is seen as responsible for this inflationary process. A central tendency is the growing inability of the government to use its procurement and distribution mechanism as a means of controlling the domestic prices of cereals and pulses. This inability stems from two sources. The first is the failure to ensure that marketed surpluses of these commodities grow at a fast enough pace to match up to consumption and buffer stocking requirements in years when demand is buoyant, as is the case recently. The second is the liberalisation of trade in many of these commodities that has seen the entry of private traders including large transnational buyers, who have cornered stocks and limited procurement by government agencies like the Food Corporation of India. According to estimates made by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), the rice stocks in the central pool as on October 1, 2008 would be only 5.49 million tonnes, just marginally above the buffer norm of 5.20 million tonnes. Wheat stocks are estimated to be only 10.12 million tonnes, which would be below the buffer norm of 11 million tonnes.

Part of the reason for this delayed response is that headline inflation figures offered by point-to-point annual increases in the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) capture trends on the ground with a substantial lag. Matters came to a head when WPI-based inflation figures relating to the week ending 15 March 2008, released at the end of last month, indicated that the annual rate of inflation had risen to 6.68 per cent, which was higher than it had been for the previous 13 months. What is more this inflation was not restricted to a few commodities but was widely spread in terms of its incidence. Inflation stood at 9.28 per cent in the case of dairy products, 19.03 per cent in the case of edible oils, 20.12 per cent in the case of oilseeds, over 9 per cent in the case of mineral oils and 26.86 per cent in the case of iron and steel. The trend has continued with the annual WPI-based inflation rate touching 7 per cent on March 22nd 2008.

The acceleration appears dramatic because going by the WPI, even as recently as February inflation was running low in the country, judged by historical standards or relative to the ceiling rate of 5 per cent set by the Reserve Bank of India. The wholesale price index for the week ended February 2, 2008 pointed to an annual inflation rate of just 4.07 per cent, whereas, during the corresponding period in the previous year annualised inflation was as high as 6.5 per cent on a week-to-week basis. However, soon thereafter the inflation rate started falling (even as concerns over inflation were still being expressed), and by October/November last year the inflation rate was hovering around the 3 per cent level. What is being witnessed now is a continuation of a trend that began in December when inflation once again edged upwards to touch 3.5 per cent in December, 4 per cent by end January 2008, 5 per cent by late February, 6 per cent at the end of the first week of March and then close to 7 per cent by mid March.

It must be noted that even a 7 per cent level is by no means high when viewed from a perspective imbued with the tolerance for single-digit inflation levels that characterised India in the past. But four factors explain the almost panic-stricken response to this rate today. First, the current level seems to be one more step in a stairway that could quickly take inflation to double digit levels. Second, the current level is well above the 5 per cent mark that has been officially declared as the acceptable ceiling rate in the wake of fiscal and monetary reform. Third, it is accepted that prices at the retail level are rising much faster and inflation as measured in terms of retail prices could be near or above double-digit levels. And, finally, all this is occurring in a period when global inflation is on the rise and policies of trade liberalisation and domestic deregulation have reduced the degree to which Indian prices are insulated from international prices.

Of these the growing distance between retail and wholesale prices is an important factor influencing the response. According to figures released by the government’s own Department of Consumer Affairs, in the last one year, in the retail market of Delhi, the price of groundnut oil has risen from Rs. 98 to Rs. 121 a kg, mustard oil from Rs. 55 to Rs. 79, vanaspati from Rs. 56 to Rs. 79, rice from Rs.15 to Rs.18, wheat from Rs. 12 to Rs.13, atta from Rs. 13 to Rs.14, gram from Rs. 32 to Rs. 38 and tur from Rs. 35 to Rs. 42. In fact, figures collated by Price Monitoring Cell of the Department of Consumer Affairs establish that in the case of a few commodities there is huge difference between inflation as measured by retail prices (collected from and averaged across 18 reporting centres nationwide) and the wholesale price index. In the case of rice, inflation over the year ending March 15 stood at 7.88 per cent as measured by the WPI, whereas it worked out to a huge 20.86 per cent in terms of average retail prices. In the case of vanaspati too the inflation rate stood at 8 and 22 per cent respectively.

These differences are bound to be reflected in the consumer price indices for agricultural labourers and industrial workers, which not only give greater weight to some of the essential commodities that have seen high rates of price inflation, but are also based on the retail prices of these commodities. Unfortunately the lag in the release of consumer price indices is much greater than in the case of the WPI, the most recent figure being for the month of February 2008. Yet, going by the consumer price indices the annual month-to-month rate of inflation stood at 6.38 per in February 2008 for agricultural workers and a much lower 4.69 per cent for industry workers. But figures based on the March indices are likely to be much higher given the most recent trends in prices revealed by other sources.

A combination of domestic and international factors is seen as responsible for this inflationary process. A central tendency is the growing inability of the government to use its procurement and distribution mechanism as a means of controlling the domestic prices of cereals and pulses. This inability stems from two sources. The first is the failure to ensure that marketed surpluses of these commodities grow at a fast enough pace to match up to consumption and buffer stocking requirements in years when demand is buoyant, as is the case recently. The second is the liberalisation of trade in many of these commodities that has seen the entry of private traders including large transnational buyers, who have cornered stocks and limited procurement by government agencies like the Food Corporation of India. According to estimates made by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), the rice stocks in the central pool as on October 1, 2008 would be only 5.49 million tonnes, just marginally above the buffer norm of 5.20 million tonnes. Wheat stocks are estimated to be only 10.12 million tonnes, which would be below the buffer norm of 11 million tonnes.

In the past this was not a problem because either demand was depressed or because the government responded to the situation by using its foreign exchange reserves to import food and augment domestic supply. During 2006 and 2007, nearly 7.5 million tonnes of wheat were imported by the Centre to augment buffer stocks. However, given what has been happening to global prices, imports have been at prices much higher than that paid to domestic farmers, swelling the subsidy paid to cover the difference between the import price and the domestic sale price. Across the world, food prices, especially those of staples like grains, have been rising sharply in recent months. Wheat epitomises the trend, with international prices estimated to have risen by close to 90 per cent just during this year.

The willingness to pay higher prices for imports even while domestic producers are not guaranteed (with price controls and subsidies) a remunerative return above costs, makes it difficult to sustain the differential between the lower domestic and higher international prices. Stung by the criticism that the government is paying farmers abroad more than it offers Indian farmers, the CACP has decided to hike the minimum support price, especially of rise. The Commission for Agriculture Costs and Prices has recommended that the minimum support price (MSP) for paddy be fixed at Rs. 1,000 a quintal for the common variety and at Rs. 1,050 a quintal for the A grade variety for the 2008-09 kharif marketing season. This compares with the currently prevailing MSP (including bonus) of Rs. 745 and Rs.775 a quintal respectively. If the recommendation is accepted, as is likely, the price of paddy would be on par with wheat, whose support price for the rabi season was fixed at Rs. 1,000 a quintal as against Rs. 850 a quintal the previos year. These changes, which reflect the desire to calibrate domestic to international prices, are setting off expectations of a sharp increase in the price of primary articles. The speculation that ensues is seen as partly triggering the current inflation in food prices.

But these developments are not necessarily driven by a concern for India’s farmers. They are also a consequence of the government’s decision to allow private players, including large international firms, a major role in domestic markets. Even though production of wheat during 2006-07 is estimated at close to 75 million tonnes as compared with 69 million tonnes in the previous year, procurement fell short of expectations because the procurement price of Rs. 8.5 a kg ruled well below market prices that ranged between Rs.10 and Rs.12 a kg. Though procurement in 2006-07 was, at 11.1 million tonnes, higher than the 9.2 million tonnes recorded in 2005-06, it was way below the levels of 16.8 and 14.8 million tonnes recorded in 2003-04 and 2004-05. Figures from the Food Corporation of India indicate that total procurement for the public distribution system has declined from 30 per cent of production during 2001-02 to 15 per cent in 2006-07. This implies that with the change in market conditions after liberalisation some degree of upward adjustment of the floor set by procurement prices is unavoidable, if buffer stocks are not to fall below comfort levels.

To this should be added the effects of the increase in oil prices, of Rs. 2 a litre for petrol and Rs. 1 a litre for diesel. The government claims that this hike is moderate and inevitable, given the sharp increase in international oil prices. However, it is not that there was no option. The petroleum sector contributes more than Rs.90,000 crore by way of indirect taxes to the Centre and Rs.60,000 crore to the States. There is evidence of a sharp increase in direct tax collections by the Centre. So it could have foregone a part of its oil revenues by reducing indirect taxes and allowing oil companies to charge more without affecting retail prices. This is all the more important because oil products are universal intermediates, since through transportation and fuel costs they enter into the costs of most other commodities. So the second- and higher-order effects of an increase in oil prices would be greater than in other commodities. Hence, the government should have sought to delink domestic oil prices from international prices through a reduction in duties imposed on petroleum and petroleum products. Unfortunately it has chosen not to do so.

A Gap too Wide |

||||

(Inflation

as measured by retail and wholesale prices) |

||||

|

Over

last 12 months |

Since beginning 2008 |

|||

|

Retail price |

WPI |

Retail price |

WPI |

|

|

Rice |

20.86 |

7.88 |

3.74 |

1.95 |

|

Wheat |

4.06 |

3.97 |

3.17 |

1.39 |

|

Atta |

4.59 |

0.45 |

3.18 |

1.59 |

|

Gram |

3.95 |

3.32 |

4.41 |

3.84 |

|

Tur |

15.76 |

13.98 |

-3.55 |

1.74 |

|

Sugar |

-0.23 |

-6.87 |

5.56 |

0.59 |

|

Groundnut Oil |

14.71 |

10.11 |

2.97 |

5.86 |

|

Mustard Oil |

28.26 |

28.98 |

12.11 |

14.49 |

|

Vanaspati |

22.23 |

7.94 |

13.72 |

4.34 |

|

Potatoes |

4.12 |

29.41 |

-25.37 |

-5.41 |

|

Onions |

-27.19 |

-26.71 |

-30.63 |

-34.01 |

|

Milk |

8.07 |

9.71 |

1.90 |

1.94 |

|

Retail prices from FCAMIN Price Monitoring Cell, averaged over

18 reporting centres |

||||

These are not the only areas where international factors are influencing domestic prices trends. International, commodities like metals have seen prices soaring because of increased demand especially from China. Indian firms participating in this international boom through rising exports at soaring prices are obviously adjusting or manipulating domestic prices upwards. This has forced the government not only to control the rise in prices but restrict exports. The hope that greater integration of Indian and global markets would benefit consumers and not producers, whereas protectionism favours producers at the expense of consumers, has obviously been proved wrong by circumstances.

It is in this background that the argument that in the case of food, oil and steel domestic inflation is being driven by international price trends has to be judged. India was and still remains significantly insulated from global price trends especially in the case of commodities where exports are restricted for various reasons. But that has been changing as a result of the winds of liberalisation. Commodities are increasingly being divided into those directly or indirectly catered to by imports, and those where domestic production caters to both domestic and global demand. In both these cases the degree to which India has been insulated from international trends has been reduced substantially. That is a consequence of liberalisation and implies that combating inflation also requires rethinking liberalization.

Interestingly the government’s response has been exactly the opposite. It is attempting to dampen domestic price trends by resorting to more imports. This may be successful in the short run in the case of commodities like edible oils, even if at the expense of damaging effects on the livelihoods of coconut and oilseeds growers, for example, and adverse effects on domestic production in these areas in the long run. But in many other commodities import is likely to be a blunt weapon. Unless of course it is combined with a willingness to offer consumers of foreign products implicit subsidies of magnitudes that are many multiples of what some domestic consumers and producers have been offered in the past.

Even these responses are because the current inflation occurs in an election year and threatens to curtail the near 9 per cent average growth rate registered over the last five years. But there is no guarantee of success. Fiscal year 2007-08, which has just come to a close, appears to be an inflection point in the current phase of post-reform growth. This is not merely because the year saw the first significant signs of the reversal of what was an unprecedented bull run in stock markets. More importantly, the evidence suggests that the government’s ability to ensure high growth with low inflation has come to an end.

© MACROSCAN

2008